This is the second of a four part series on the history of vaccines.

In the early 1800’s, the first mandatory vaccine was attempted, by Marianne Elisa of Lucca (this was actually Napoleon’s sister). The only problem she had was actually enforcing the law. It took 50 years to develop an enforceable law, the Vaccination Act of the UK. King Charles of Spain, around the same time, set out to spread the smallpox vaccination to the Spanish colonies of the new world. He sent several children (orphans) with cowpox to South America so that they could help deliver the less severe alternative to smallpox.

source: The Historical Medical Library of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia

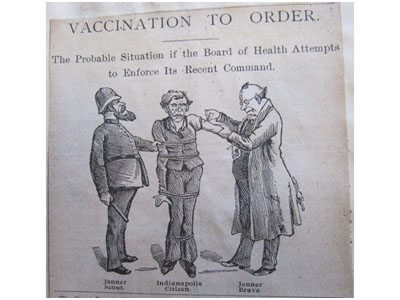

The image above shows a cartoonist’s representation of what would happen if a mandatory vaccinations became law.

The anti-vaccination movement is nothing new. It was actually started in the late 1800’s, with the first Anti-Vaccination League of America promoting the idea that smallpox was not spread by a virus, but by filth. It was an easy idea to accept, but completely untrue.

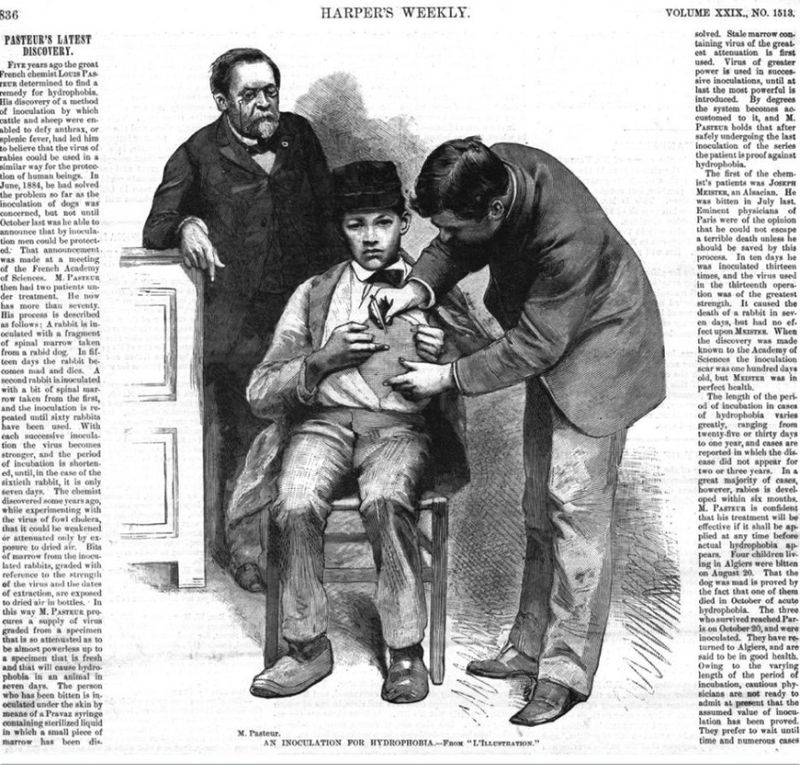

The first trial in vaccinations has always been a risky affair. Those who practice it have no guarantee of what will happen. A man by the name of Pasteur, who was not a doctor, gave the first rabies vaccine to a young boy who was recently bitten by a rabid dog.

source: americanhistory.si.edu

Rabies was derived from the word Hydrophobia, which means fear of water. The virus infects the salivary glands and swells the throat – causing intense and painful spasms in the throat and larynx. Those infected show an immense fear and panic when presented with water, or even the thought drinking. He had attempted two vaccines before, unsuccessfully, as both subjects had died. At the time, people still weren’t in favor of injecting humans with a virus or bacteria. Pasteur argued that the boy would die if he did nothing – and in this case there was nothing to lose.

Over the course of two weeks, he gave injections to the boy, who later survived. Pasteur’s work was then considered a success. Scores of people would then seek him out to provide a vaccination from the viral disease. Months later, he went on to successfully prevent rabies in a farmer who was bitten by a rabid dog.

In the third segment of this series, we’ll discuss breakthrough immunizations for diphtheria and typhoid, and how a small group of people rebelled against the vaccinations.