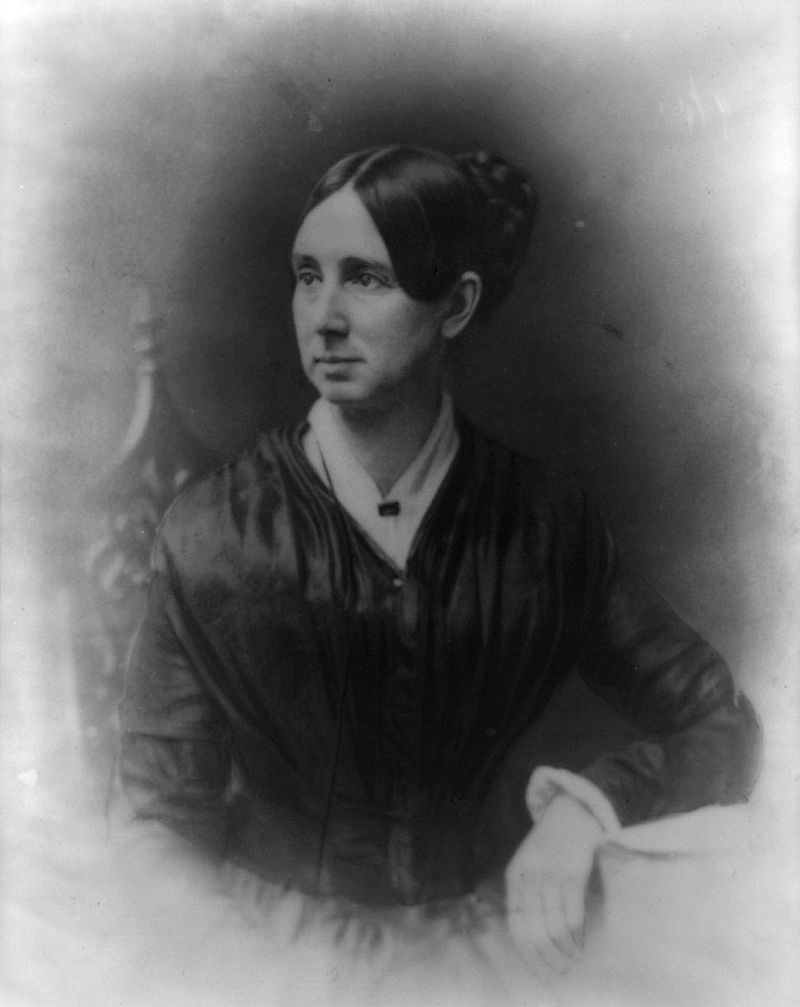

Dorothea Lynde Dix spent much of her career as an educator and social reformer to working with the mentally ill and creating some of the first mental asylums in the United States. She grew up with alcoholic and abusive parents and would suffer from poor health her whole life. At about twenty-one years old, Dix opened up a school in Boston and worked with poor children who were often times neglected. She continued to work as an educator throughout her life, serving as Superintendent of Army Nurses during the Civil War.

On April 4, 1802, Dorothea Dix was born in Hampden, Maine. Dorothea was the first child born to Methodist preacher Joseph Dix and Mary Bigelow, two more to follow. Joseph Dix spent most of his time away from the household as his wife weakened from depression. From a young age, Dorothea was in charge of the household while taking care of her two younger siblings. Her father taught her to read and write. But because of her parents’ alcoholism and abuse from her father, Dix sought out a better life when she was twelve to life with her grandmother, Dorothea Lynde Dix, in Boston.

In Boston, Dix’s wealthy grandmother encouraged her to keep going with her education. At the young age of fourteen, Dix began working at a school. This pushed Dorothea to establish schools in Boston and nearby city Worcester. Only about twenty, Dix created her own curriculum. In 1821, she opened up a school in Boston. It was an all girl’s school patronized by wealthy families, though she also opened up a school where girls from poor families could attend. Though not long after, Dix began suffering health issues. She had to take frequent breaks from teaching, so she began to write children’s stories between 1824-30. Her books were filled with morals and dictums in hopes of educating young people. Another all girls model school was established in Boston in 1831. The school only lasted for five years though because Dix had to close it due to another health breakdown.

With encouragement from her physician, Dix left for England to try and help her health problems. Prominent Quaker family, the Rathbones, who were also social reformers,, invited her to stay at their Liverpool mansion, Greenbank. There, she met English reformers Elizabeth Fry, Samuel Tuke, and William Rathbone. Many people she met believed that the government needed to pay a more direct role when it came to social welfare. Being introduced to the movement of caring for the mentally ill in Great Britain (the lunacy reform), Dorothea Dix was inspired to start working on gaining equal rights for the mentally ill in the U.S.

Returning to Massachusetts around 1840, Dix working at East Cambridge Prison, where she taught the inmates. She was horrified by the inhumane treatment of prisoners. Dix was determined to improve quality of life in these facilities by conducting an investigation of treatment for the insane throughout Massachusetts. In most towns in the state, if there was no family or friends to take care of the insane, representatives from the towns made agreements with residents to watch over them. This system was poor and ended up in most of the insane being treated poorly and abusively. In a fiery report, Dix published what she had observed directed towards the state legislature. After spending much of her time lobbying for reform, a bill was finally passed in the state legislature that expanded the mental hospital run by the state in Worcester.

Dix started another investigation in 1844. She visited every jail and almshouses in New Jersey. She prepared another memorial similar to that of the one to the Massachusetts Legislature, but this once was directed to the New Jersey Legislature. This memorial gave detailed accounts of her observations and facts she had learnt. She continuously lobbied to the legislature to act upon this problem and provide proper funds towards a new facility to care for the insane in New Jersey. Dix made sure she cited many cases to emphasize to the legislature that it was important the state take responsibility for the insane and their suffering.

One of Dix’s examples was a man that had been a legislator and jurist. However, this man had gone through many hardships as he grew older and eventually became insane. When Dix met him, he was in the basement of the county almshouse lying on a small bed without the comfort and care he needed. Many New Jersey legislature members knew exactly who she spoke of. On January 23, 1845, Joseph S. Dodd introduced Dix’s long report to the Senate. The following day, his resolution to authorizing an asylum passed. Appealing to the New Jersey legislature, the first committee finished their report just over a month after on February 25, 1845. Because of high taxes that would be used to support the resolution, many politicians, secretly, opposed it.

This did not stop Dix from lobbying for even more support, though. She wrote letters to editorials to try and gain support to build a facility to care for the insane. Throughout the session she met with many legislators along with holding evening group meetings in her home. On March 14, 1845, the act of authorization was taken up and read for the last time. The bill passed on March 25, 1845 to establish a state facility for the mentally ill.

Still, Dix was unstoppable. Next, she traveled to New Hampshire and then Louisiana. She sent reports to the state legislatures after documenting living conditions for the insane. Dix met and worked with committees to draft the necessary reform bills. The following year in 1846, Dix studied mental illness in Illinois. She suffered another round of health issues, spending that winter recovering in Springfield, Illinois. In January of 1847, Dix sent a report to the legislative session and a legislation was adopted to establish the first state mental hospital in Illinois.

After her time in Illinois, Dix made her way to North Carolina in 1848. She called that a reform be made to improve the quality of life for mentally ill patients. The North Carolina State Medical Society was formed in 1849. Because of this, the state legislature authorized for an institution named in honor of Dorothea Dix for the mentally ill to be built in Raleigh, the capital of North Carolina. It took six years, but the hospital eventually opened in 1856. Almost twenty years later, another state institution for the mentally ill was authorized in 1875. In Morganton, North Carolina, the Broughton State Hospital was established. Next, the state created another hospital for the mentally ill called the Goldsboro Hospital for the Negro Insane was built near Piedmont. Dix was biased that mental illness was not related to minorities, but instead educated whites.

Dix played a role in forming the first Pennsylvanian mental hospital as well. The Harrisburg State Hospital, originally known as the Pennsylvania State Lunatic hospital until 1937, was built in 1851. She established a library and reading room for the hospital two years later.

In 1853, Dix traveled to Nova Scotia, the British colony in Canada, to study how the insane were treated there. She visited Sable Island, a remote island, to investigate reports that insane patients had been left abandoned on the small island. Dix also helped out with rescuing people from a shipwreck. When she returned to Boston, Dix led a campaign to help those left on the island.

The peak in Dix’s career was when the Bill for the Benefit of the Indigent Insane was introduced in the United States Legislature was introduced. If this bill were to be passed, 12,225,000 acres of Federal land would go toward helping the insane and “blind, deaf, and dumb”. Money from sales would be given to each state to build and maintain their own hospitals for the mentally ill. Though the bill was passed by both the House and Senate, President Franklin Pierce vetoed it in 1854. Pierce argued that social welfare was not a federal responsibility, and instead a state one.

Angry and hurt that her bill had been vetoed, Dix took some time off and traveled to England in 1884-85. She reunited with her old friends, the Rathbones, and investigated madhouses in Scotland. Because of her work conducting investigations in Scotland, the Scottish Lunacy Commission was formed to oversee reform.

Previously, Dix had been made Superintendent of Army Nurses under the Union Army when the Civil War broke out in 1861. British Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman in the U.S. to earn a medical degree, was beat for the position when Dix was given the appointment. Though Dix was successful independent, her qualities were not effective when it came to managing large groups. She was put in charge of all female nurses in the Union Army when crises broke out during the war.

For nurses during the war, Dix set a strict rule of guidelines. All volunteer nurses had to be plain-looking and between the ages of 35-50. No jewelry or cosmetics of any sort was tolerated and only simple black or brown dresses without hoops were permitted. By doing this, Dix believed she was avoiding vulnerable and attractive young women being sent to hospitals as nurses. She feared that men, both doctors and patients, would exploit and mistreat them. Many volunteer nurses were fired because Dix had not worked with, either trained or hired them herself. She didn’t trust Catholic nuns, despite the fact that many of them had volunteered as army nurses during the war.

Often times she found herself in arguments with Army doctors. They argued with her because she was constantly firing nurses and wanted control of medical facilities. Most doctors and surgeons actually didn’t want any female nurses in their hospitals. In October 1863, the War Department introduced Order No.350. This gave Surgeon general Joseph K. Barnes and Superintendent of Army Nurses Dorothea L. Dix the rights to hire female nurses. Doctors were able to assign employees and volunteers for their own hospitals though. Because of this order, Dix was no longer in complete responsibility. She influenced many nurses of the time such as Dr. Mary Edwards Walker and Clara Barton that would go on to have larger medical careers after the war. In August 1865, Dix resigned from her position. Many considered this to be a failure in her career, but the war had ended in May.

Even though she was in charge of nurses in the Union Army, often times her nurses were the only ones to attend to wounded confederate soldiers. One of Dix’s nurses, Georgeanna Woolsey stated that the surgeon in their camp tended for the Union and Confederate soldiers. They may have been enemies, but the nurses and doctors were kind enough to extend their help to the wounded Confederates. More than 5,000 wounded Confederate men were left behind after the Battle of Gettysburg. Dix’s nurses treated all of these men and made sure they got the proper help.

Dix remained well respected because of her dedication during the war as Superintendent of Army Nurses. She put aside her work on helping the mentally ill for the time being and focused solely on the war. Dix was given two national flags as rewards for her hard work.

After years of hard work advocating for reform for the insane and looking over nurses in the Civil War, Dix moved to Morris Plains into the New Jersey State Hospital at not quite eighty years old. For as long as she lived, the state had given her a designated private suite in the hospital. She may have been constantly ill, but Dix continued to write to her friends across the world in England and Japan, among others. On July 17, 1887, eighty-five year old Dorothea Lynde Dix passed away. She was buried in Cambridge, Massachusetts at mount Auburn Cemetery.