PHOTO: livescience.com

ASWAN, EGYPT – Egypt’s antiques ministry announced an amazing new discovery on May 24 of a new, non-royal burial found in a necropolis near Aswan, Egypt.

Excavation leader Alejandro Jiménez-Serrano, an Egyptologist at the University of University of Jaén in Spain, made the discovery while leading an archaeological dig in the necropolis at Quibbet el-Hawa, just across the Nile from Aswan. They uncovered the upper part of a burial chamber that belonged to a tomb dating back to the fifth century AD. They thought the area had been disturbed, but, when they dug deeper, they found that the chamber wasn’t a tomb chamber at all, but a shaft leading to a more extensive network of rooms.

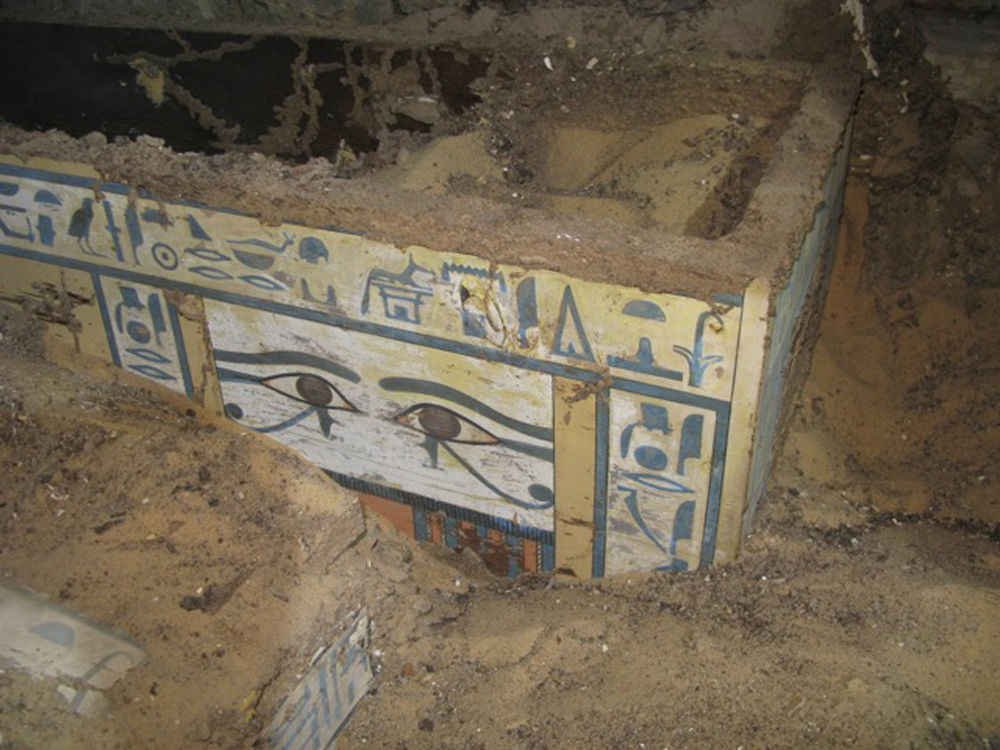

At the bottom of the shaft, Jiménez-Serrano said, was a tiny window. In a discovery eerily like Howard Carter’s discovery of King Tutankhamen’s tomb in the late 1800s, our archaeologist shone a flashlight through the little window and saw hieroglyphs staring back at him. The hieroglyphs were engraved on a coffin belonging to an ancient Egyptian woman named Lady Sattjeni.

The hieroglyphics Jiménez-Serrano saw staring back at him were, in fact, double Eyes of Horus, or the Wadjet. It’s an immensely significant symbol of protection, royal power, and good health. It was, no doubt, painted onto Lady Sattjeni’s coffin in order to protect her soul both here, and in the afterlife, and to look on and guard her tomb and earthly possessions that she would need after her death.

Qubbet el-Hawa, where Lady Sattjeni’s tomb was found, is one of the most important nonroyal necropolises of ancient Egypt. It has both an immense number of tombs, and brilliantly preserved artifacts and inscriptions that tell us what life was life for the important officials of the nearby town of Elephantine, the capital of southern Egypt. It dates back to about 2200 BC, and is home to over 100 tombs. Each of them is beautifully decorated, and many have inscriptions that have been absolutely invaluable to our narrative of Egyptian life and history.

From what Jiménez-Serrano and his team could garner from her tomb, Sattjeni was the second daughter of one of the most important figures in Egypt’s 12th Dynasty, the governor Sarenput II. Her brother, Ankhu, died shortly after their father did, and there were no male successors. This meant that Sattjeni and her sister had complete rule over the city of Elephantine. Her sister married an official called Heqaib II, but because later records in Sattjeni’s tomb say she also married Heqaib, it’s probable that her sister did not live a very long time. Settjeni had two children, both of whom ruled Elephantine after her death.

From the information provided by Sattjeni’s tomb, it’s apparent that even non-royal Egypt followed the example of Egypt’s Pharoahs and ruling families. Women were holders of Dynastic Rights (something that you don’t see too often in the ancient world!). Sattjeni’s family believed they were descended from a local god, a ram-headed god called Khnum, and they probably, just like the royal family, married brother to sister in order to keep the divine blood “pure”.

Khnum was, interestingly enough, one of the earliest Egyptian deities. He is often depicted as the god of the source of the Nile River, and it makes sense that Sattjeni’s family would want to associate with him, since Elephantine sat right on the Nile. He’s often talked about as the “Divine Potter”, and “Lord of Created Things”, and Egyptians believed that he created human children and all of the other gods. He’s in charge of fertility, in a way, and prosperity, and so he’s a pretty good god, out of all of them, to associate your family with and have on your side!

Sattjeni’s burial will continue to be looked after by Jiménez-Serrano, his team, and the Egyptian antiquities ministry. It’s proving to be an enormous find toward what we know about how members of Egyptian society lived.