Thomas Paine is perhaps best remembered for his influential pamphlets written at the start of the American Revolution, Common Sense (1776) especially. He was an English-American philosopher, political theorist, political activist, and revolutionary and is considered to be a Founding Father of the U.S. Paine’s ideas were very influential when America was declaring independence from Britain in 1776.

On January 29, 1736, Thomas Pain was born in Thetford, Norfolk, England. His father, Joseph Pain, was a Quaker, and his mother, Frances Cocke Pain, was an Anglican. Though he was born with the name Pain, he used Paine in 1769 and throughout the rest of his career.

From 1744 to 1749, Paine attended Thetford Grammar School. At the time, education was not required by law. At thirteen, Paine began working with his father, who was a stay maker (stays were the thick ropes you used for sailing ships). There have been some sources that say Paine and his father made corsets. However, most historians say that Paine’s enemies only used that as slander against him. Stays also had to do with corsets, but those were not the kind of stays Paine made.Briefly, Paine enlisted as a privateer in his late teens. He returned home in 1759 and became a master stay-maker. Paine soon established his own shop located in Sandwich, Kent.

Mary Lambert married Thomas Paine of September 27, 1759. Not long after their marriage, his business collapsed. The couple moved to Margate, but Mary went into early labor and, along with their child, died.

Paine returned to Thetford in July 1761 so he could work as a supernumerary officer. A supernumerary officer is an officer without an assigned role that takes over for other officers when needed. Paine later became an Excise Officer in Grantham, Lincolnshire in December of 1762. He was transferred in August of 1764 to Alford, Lincolnshire. For “claiming to have inspected goods he did not inspect”, Paine was dismissed from his spot as an Excise Officer on August 27, 1765. The following July, he requested the Board of Excise reinstate him. They granted this the next day if there were any vacancies. While Paine waited for a spot to open up, he began working as a stay-maker once again.

In 1767, Paine was appointed to a position that was located in Grampound, a village in Cornwall. Shortly after, he was then asked to leave this position and to wait for another vacancy. So, Paine began teaching in London. On February 19, 1768, he was appointed to Lewes, Sussex. Paine lived above the Bull House, a fifteenth century tobacco shop owned by Samuel and Esther Ollive.

Lewes was where Paine first found himself becoming involved in civic matters. He appears in the Town Book as a member of the town’s governing body, the Court Leet. Paine was also a member of an influential local church group, the parish vestry, responsible for parish work such as collecting taxes and tithes so they could distribute them among the poor.

Thirty-four year old Thomas Paine married Elizabeth Ollive, the daughter of his landlord, on March 26, 1771.

Along with other excise officers, Paine asked for higher pay and better working conditions from Parliament from 1772-73. This was when Paine published his first political work, a twenty-one page article called The Case of the Officers of Excise. He spent that winter in London distributing the 4,000 copies of the pamphlet to members of Parliament and others in the city.

Once again, they dismissed him from the excise service in the spring of 1774. This time it was due to being absent without permission. On top of that, his tobacco business was failing. As to avoid debtors’ prison, Paine sold all his household possessions to pay off his debts on April 14, 1774. On June 4, he formally separated his wife Elizabeth and moved to London.

It was in London that Paine was introduced to Benjamin Franklin by Commissioner of the Excise George Lewis Scott. Franklin suggested that Paine leave Britain and immigrate to America and also gave him a letter of recommendation. That October, Paine emigrated from his home in Britain to the colonies. He arrived at Philadelphia on November 30, 1774 after a rough voyage he barely survived. The water supplies on the ship were bad and five of its passengers were killed from typhoid fever.

Paine was too sick to even disembark when he arrived in Philadelphia, Benjamin Franklin’s physician had gone to welcome him to America and ended up having to carry Paine off the ship. It was six weeks until Paine finally recovered. He took an oath of allegiance and became a citizen of Pennsylvania. That January, he became the Pennsylvania Magazine’s editor.

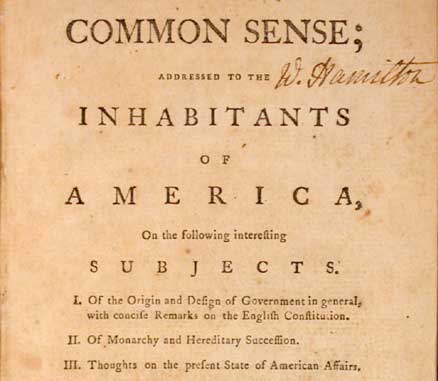

His claim to fame were his many pamphlets. Common Sense, is, however, still by the far most popular. In it, he wrote of his sentiments for independence in 1776, the same year the Declaration of Independence was signed and adopted. On January 10, 1776, it was published in Philadelphia anonymously “by an Englishman”. It was a quick success. In only three months, the forty-eight paged pamphlet sold over 100,000 copies. It sold a total of 500,000 copies during the American Revolution, including unauthorized editions. Originally, Paine had titled it Plain Truth. Benjamin Rush, Paine’s friend, had been the one to suggest he instead name it Common Sense.

The pamphlet would be passed around when it came into circulation the same month it was published, even being read aloud in taverns. This greatly contributed to the spreading idea of Republicanism. Enthusiasm for separation from the British grew even more along with recruitment for the Continental Army. Paine’s argument was not only new, but also convincing. It advocated to break completely with history. Americans were disgusted with threats of tyranny, and Paine’s pamphlet provided just the solution for it. Common Sense became the most widely read pamphlet in America during the Revolution.

Essentially, Paine was attacking George III by attacking monarchy in his pamphlet. The Americans normally directed their resentments towards the ministers and Parliament, not the king himself, whereas Paine made it clear that he believed it all to be the king’s fault and responsibility. Common Sense was written in a direct and lively style that captured the attention of many. It denounced Europe’s decaying despotisms and called hereditary monarchy absurd.

Paine’s ideas in Common Sense were not all his. Instead, he used other ideas as means to arouse resentment towards the British Crown. His style of political writing was pioneered by him to suit the democratic society he envisioned for America. He wrote clearly and concisely instead of formally to make his complex ideas understandable to average readers of the time period. Paine’s way of writing in Common Sense, according to scholars, may have been part of the reason, but not the only one, for it’s success.

While the pamphlet most likely had very little influence on the Continental Congress and the decision to declare independence with the Declaration of Independence. Instead, Common Sense’s main contribution was that it sparked public debate on the formerly rather muted topic of independence.

Loyalists, on the other hand, attacked the pamphlet vigorously. James Chalmers from Maryland attacked him in Plain Truth (1776), calling Paine a political quick. Chalmers said that the government would “degenerate into democracy” without monarchy. Though Loyalists were not the only ones objecting to Common Sense. In fact, some revolutionaries objected to it. John Adams would later on call it a “crapulous mess.” Adams did not agree with the form of radical democracy Paine was trying to promote. This was that men who were not property owners should be permitted to vote and hold public office. In response, Adams even published Thoughts on Government (1776) to advocate for the type of government he favored, a more conservative republicanism approach.

Paine published The American Crisis late in 1776, the same year as Common Sense. It was a series of pamphlets intended to inspire Americans battling the British. He compared the conflict of the good American dedicated to civic virtue versus the provincial and selfish man. General George Washington had the first pamphlet in the series of The American Crise read aloud to his soldiers to inspire them.

In 1777, Paine became the Congressional Committee on Foreign Affairs’ secretary. He alluded to secret negotiations with France the following year in pamphlets. His enemies used this as a way to denounce him for indiscretions. Paine’s conflict with Robert Morris and Silas Deane became a scandal that eventually led to him being expulsed from the Committee in 1779.

Paine had pleaded the New York State to recognize his political services with an estate in New Rochelle, New York. Pennsylvania and Congress took Washington’s suggestion and gave Paine money as well. He also served as an aide to prominent General Nathanael Greene during the Revolution.

Silas Deane, an American diplomat, had been appointed to secretly travel to France by Congress in 1776 with the goal of influencing the French to fund the Continental Army. Paine was openly critical of Silas Deane, as he saw Deane as a war profiteer that had little respect for principle. He labeled him as unpatriotic. Paine also demanded they publicly investigate Robert Morris’, a primary financier of the Revolution, financing. But Paine’s criticisms ended up turning against him. He effectively embraced France in the Pennsylvania Packet when he wrote that France had “preface [their] alliance by an early and generous friendship.” Immediately, President of the Congress John Jay spoke out against Paine. The controversy soon became public, leading to the denouncement of Paine for being unpatriotic for criticizing an revolutionary. Deane supporters even physically assaulted Paine on the streets twice.

When Colonel John Laurens left for France, he was accompanied by Paine, who is credited for initiating their mission. In March of 1781, they landed on France. That August, they returned to America, and with them, 2.5 million silver livres. These livres were apart of 6 million and a loan of 10 million. Most likely in the company and under the influence of Benjamin Franklin, they conducted meetings with the King of France. When they returned, Paine and most likely Laurens “positively objected” that Washington should propose that he be remunerated by Congress for his services to the country. While in Paris, Paine had also become acquainted with influentials and also helped to organize money to raise for the Bank of North America to supply the army. The U.S. Congress later gave him $3,000 for his service to the nation in 1785.

The ambassador to the Netherlands, Henry Laurens (John Laurens’ father), had been captured on a trip there by the British and Paine proceeded to the Netherlands instead to continue negotiating loans.

In 1783, Paine purchased his first, and only, house in Bordentown City, New Jersey. He periodically resided in the home until 1809 when he died.

A bridge designed by Paine was built across the Schuylkill River in 1787 in Philadelphia. As he continued to work on single-arch iron bridges, he went back to Paris. His only friends in France were Lafayette and Jefferson and he continued to correspond with Franklin. Franklin provided Paine with letters of introductions to use to gain associates and contacts abroad.

Paine returned to London later that year after visiting Paris. On August 20, 1787, another pamphlet called Prospects on the Rubicon: or, an investigation into the Causes and Consequences of the Politics to be Agitated at the Meeting of Parliament was published. At the time, there were increasing tensions between Britain and France. In his pamphlet, Paine urged the British Ministry to think of what the consequences of a war with France would be.

While in London, Paine found himself engrossed with the ongoing French Revolution. In 1790, he visited France again. And when Edmund Burke, a conservative intellectual, launched his counter revolutionary pamphlet, Reflections on the Revolution in France, Paine set out to refute it. Thus, he wrote Rights of Man, a long pamphlet of 90,000 words that discriminated monarchies and traditional social institutions. He gave the manuscript to Joseph Johnson, a publisher from London. When Johnson was visited by government agents to persuade him not to publish the pamphlet, Paine fave it to J.S. Jordan, another publisher instead. Shortly after, he returned to Paris, as advised by William Blake. Three of Paine’s good friends (William Godwin, Thomas Holcroft, and Thomas Brand Hollis) were charged with the publication details of the pamphlet. On March 13, 1791, it appeared, selling almost a million copies.

Even as the government was campaigning to discredit him, Paine still published Rights of Man, Part the Second, Combining Principle in Practice the following February. It was a detailed pamphlet that described a representative government with enumerated social programs that would remedy the numbing poverty of commoners by means of progressive tax. This volume was reduced in price to ensure that it circulated around the country and even gave birth to reform societies along with impacting many.

Government agents, however, began following Paine along with starting mobs, hate meeting, and burnings. A fierce pamphlet war ensued as well. Paine defended and attacked several works. Authorities were aiming to get Paine to leave Great Britain. Though he was soon tried in absentia and also found guilty, they never executed him.

Rights of Man, Part II was published in French in April 1792. It had originally been dedicated to Lafayette, but the translator eliminated that because he believed that Paine thought of the Marquis too highly. At the time, Lafayette was seen to be a royalist sympathizer.

“If, to expose the fraud and imposition of monarchy … to promote universal peace, civilization, and commerce, and to break the chains of political superstition, and raise degraded man to his proper rank; if these things be libellous … let the name of libeller be engraved on my tomb,” said Paine in response to sedition and libel charges that summer.

An enthusiastic supporter of the French Revolution, Paine was granted honorary French citizenship along with other prominent American politicians, among them Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, and George Washington. It had been granted to him for the sensation Rights of Man, Part II was creating in France. And even though Paine could not actually speak French, he was elected to the National Convention to represent the district of Pas-de-Calais. He was then selected as one of nine deputies to draft a constitution for the French Republic as a part of the Convention’s Constitutional Committee a few weeks later. Though he argued against the execution of Louis XVI, he did vote for the French Republic. His reasoning for voting against it was because he believed they should first exile Louis XVI to the United States because France had aided America in the American Revolution and because of a moral objection to capital punishment just in general. As Paine was giving a speech defending Louis XVI, Jean-Paul Marat interrupted him. He stated that the translator was distorting Paine’s words before Paine himself could provide a copy of his speech for proof of direct translation.

When a decree was passed at the end of 1793 that banned foreigners from palaces in the convention, Paine was arrested and then imprisoned on December 28.

Joel Barrow attempted to secure Paine’s release by circulating a petition among Americans residing in paris, but was unsuccessful. Sixteen American citizens were permitted to plead for Paine’s release to the convention. The President of the Committee of General Security Marc-Guillaume Alexis Vadier refused to acknowledge that Paine was in fact an American citizen. He said that he was a citizen of a country at war with France. Paine tried to protest that he was a citizen of an allied country to France, not one at war with them. The American minister to France, Gouverneur Morris, did not press him on this claim. Later on, Paine would write that Morris had connived at him being imprisoned. Paine barely escaped being executed. In fact, the only reason he was not executed was because his cell door was opened. The gaoler was to leave a chalk mark to indicate if the prisoner was to be collected for execution, but as the gaoler made his rounds, Paine’s door just happened to be open. Instead of a chalk mark supposed to be on the inside of his door, it ended up on the outside. At the time, Paine had been receiving official visitors.

In November of 1794, Paine was released from prison. This was largely because of James Monroe, who was the new American minister to France at the time. Monroe was successfully able to argue Paine’s case for having American citizenship. Then, Paine was even readmitted to the Convention the following July. He was only one of three to oppose the 1795 constitution. This was because it did not grant universal suffrage, unlike in the Montagnard Constitution of 1793.

A bridge designed by Paine was built over the Wear River in Sunderland, England in 1796. It was called the Sunderland arch and had the same designs as the bridge he designed on the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia. Paine even received a British patent for single-span iron bridges. He later on developed a smokeless candle and worked with John Fitch to develop steam engines.

Paine moved to Paris in 1797, living with Nicholas Bonneville, a French bookseller, and his wife, Marguerite Brazier. He and Bonneville’s other guests aroused suspicions from the authorities. Royalist Antoine Joseph Barruel-Beauvert was also being hid at Bonneville’s home. Paine had believed that America had betrayed revolutionary France under President John Adams. When Bonneville was briefly sent to jail however.

Bonneville took refuge in Evrek with his father, as he was still under police surveillance, in 1800. Paine joined him and helped him with translating the “Covenant Sea”. Paine supposedly had a meeting with Napoleon that same year as well. Napoleon, who had claimed that he kept a copy of Paine’s Rights of Man under his pillow when he slept, said to Paine that “a statue of gold should be erected of you in every city in the universe.” Paine and Napoleon discussed the best way to invade England. Paine would remain in France until 1802.

When Paine left for the U.S., Bonneville’s wife and their three young sons, Benjamin, Louis, and Thomas (Paine was his godfather), accompanied him. Marguerite, Bonneville’s wife, would care for Paine until his death, and he even left most of his estate to her. Bonneville did not join his wife in the U.S. until Napoleon fell in 1814.

The U.S. was in the early stages of the Second Great Awakening when Paine returned. The religiously devout were given a reason to dislike Paine because of his The Age of Reason. It followed the tradition of 18th century deism, challenging institutionalized religion and the Bible’s legitimacy. The Federalists were also attacking him, but for the ideas of government he listed in Common Sense along with his association with the French Revolution and friendship with President Thomas Jefferson. Paine settled into New Rochelle, but was denied the rights to vote by Gouverneur Morris, who refused to recognize him as an American citizen. Washington did nothing to aid Paine with this either.

At seventy-two years old, Thomas Paine died at 59 Grove Street, Greenwich Village, New York City on June 8, 1809. Marguerite Brazier buried him under a walnut tree on his farm because the Quakers refused to allow it to be buried in their graveyard in New Rochelle like Paine had requested. In 1819, the English William Cobbett dug up Paine’s bones to take them back to England and give him a heroic reburial on his native soil. It never ended up happening though. Paine left most of his estate and 100 acres of his farm to Marguerite so she could educate her sons.