PHOTO: Wikimedia

Last week on Battles That Made History, we covered the famous Siege of Yorktown. It was the battle that would bring about the downfall of the British occupation of the American Colonies. Because of Yorktown, the Americans were able to seize their independence from Britain and emerge as a new nation.

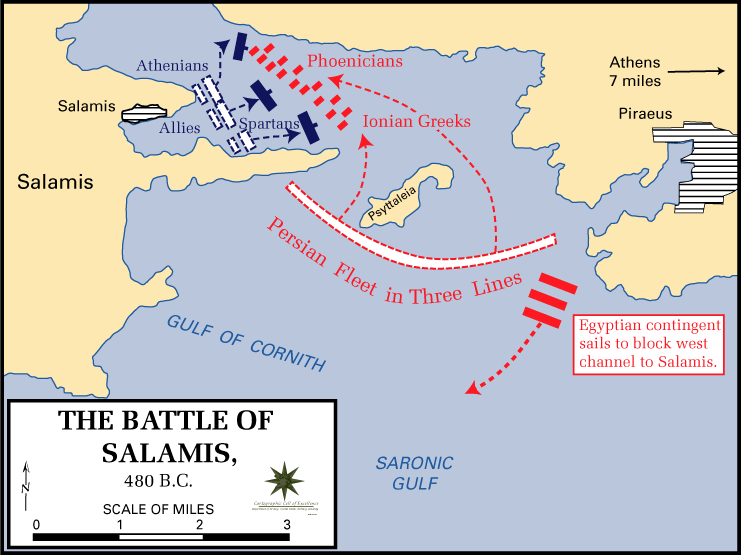

This week, we’re talking about Salamis Bay, one of the most decisive naval battles of all time. If Salamis Bay had gone any differently, Western Civilization as we know it today would have never existed in the first place.

It all began in 480 BC. Of course, that was the year everything ended, too.

Outnumbered, Outgunned

It was August of 480 BC. The Athenians had fled to Salamis Bay after the defeat of the Spartans at Thermopylae. Everything was looking pretty grim for the upstart Greek city-states. With no one standing in their way, the Persian Army swooped into Greece, quickly captured Athens, and started to make its way after the fleeing Greek army.

![Bust of Themosticles [PHOTO: roadrunnersguidetotheancientworld.com]](https://historythings.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/themistocles-231x300.jpg)

Bust of Themosticles [PHOTO: roadrunnersguidetotheancientworld.com]

Themosticles believed that the Delphic oracle meant that Salamis would bring death to the Persians, not the Greeks, and that a “wooden wall” meant the Greek fleet. He proposed that they try to trap the Persian fleet in Salamis Bay and pick each ship off, one by one.

It was a desperate situation. The Persians outnumbered them 10 to 1. Many Greeks had already lost heart, especially after, when some Athenians took the Delphic prophecy literally, stayed behind, walled themselves in, and were killed. They’d lost Athens, they’d lost Thermopylae, and they thought they had lost Greece, too.

Besides, how could they hope to win a naval battle when they only had 371 small triremes, and the Persians had a whopping twelve thousand?

Set ‘Em Up, Knock ‘Em Down

By September, the jury was still out on what to do. Many of the Greeks wanted to fight closer to Corinth so they could retreat to the mainland in case of defeat, or withdraw and let the Persians attack by land.

![Xerxes I [PHOTO: freeread.com]](https://historythings.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/download-1.jpg)

Xerxes I [PHOTO: freeread.com]

Time was running short. The Persians were closing in. Already the much larger Persian fleet had set sail for Salamis Bay. Xerxes was, in fact, so sure that they would win that he set up a throne high on the slopes of Mount Aegaleus. There, he had a great view of the bay. He planned watch the battle, enjoy his victory, and record the names of clever and courageous commanders so they could be commended later.

With their list of options starting to get smaller and smaller, the Greeks finally decided to listen to Themistocles, and began preparations for a naval battle. They lined their ships up in the bay, lined their men up on the shore, and Themosticles sent an informer to Xerxes to make Xerxes believe that the Greeks could not agree on the location of the battle, and would retreat.

Xerxes took the bait. The Persian army sailed to the bay and blockaded Salamis, waiting, watching, believing they were going to catch the Greeks in retreat.

![Statues of Queen Artemisia (left) and King Mausollos (right). [PHOTO: bodrumturkeytravel.com]](https://historythings.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/sculptures-of-king-mausollos-and-artemisia.jpg)

Statues of Queen Artemisia (left) and King Mausollos (right). [PHOTO: bodrumturkeytravel.com]

The Persian king merely waved the warning away and put it out of his mind, convinced that his victory was inevitable.

The Battle

Morning dawned the next day. Historians have dated it September 28, but nobody’s actually sure of the exact time of the battle.

The Persians were exhausted from a long night, lying awake, waiting for the Greek retreat. The Greeks, however, were well-rested. They’d slept on their ships and were prepared for the ensuing battle.

It was the Persians that made the first move. They sailed into Salamis Bay, impatient from all of the waiting. Almost immediately, the closet Greek fleet, the Corinthians led by Adeimantus, feigned retreat, drawing the Persians into the narrow straits of the bay.

For a moment, nobody moved. Both fleets held their breath, waiting for their generals to give the signal to attack. Then, out of nowhere, a Greek trireme rammed into the side of a Persian ship. Pandemonium broke loose.

PHOTO: wikimedia

The Greek triremes were smaller and faster than the clunky Persian ones. The Athenian and Aeginan triremes zipped around the Persian fleet to flank them, so that when the Persians realized their mistake, it was too late. They were trapped. The wind turned against them, bringing the fleet to a standstill. The only direction they could move was deeper into the straits.

Only 100 Persian triremes could fit into the gulf at a time. Each wave was subsequently rammed into the straits by the Greek ships and boarded by Hoplites. The Persians weren’t expecting to have to fight hand-to-hand, and were no match for the better-equipped, well-rested Greeks.

![Greek Trireme [PHOTO: wikimedia]](https://historythings.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/trireme-300x232.jpg)

Greek Trireme [PHOTO: wikimedia]

The Persians suffered far more casualties on the sheer fact that most of the Persians didn’t know how to swim. Xerxes even lost his brother. The few Persian soldiers that did survive to make it to shore were killed by the Greeks the minute they set foot on land.

Xerxes saw it all. During the bloodbath, as he watched his male generals falling left and right as they scrambled to escape the trap, he remarked: “My female general has become a man, and my male generals all have become women”, because even though Artemesia switched sides halfway through, she was the only one of his generals that had succeeded in sinking several Greek ships.

Aftermath

Salamis bay was the turning point in the Persian Wars. After the embarrassing defeat, Xerxes was forced to retreat to the Hellespont, where a line of Persian ships formed a wooden bridge to safety in Persia. He meant to march his army across, but before he could, the Greek ships sailed in and punched a hole in the last remnants of the Persian fleet, effectively trapping the Persian army in Greece.

Xerxes fled to Persia. He would never return. All in all, the victory at Salamis saved Greece from being absorbed into the Persian Empire, ensuring the emergence of Western civilization as we know it today and Greece as a force to be reckoned with. Persia would think twice before attempting to invade ever again.