NANGGU, SOLOMON ISLANDS – Archaeologists from Australia and New Zealand working on a Pacific site have discovered obsidian tools used for tattooing by Pacific Islanders. They’re hoping their discovery will bring some insight into the tattooing practices of the ancient cultures of the Pacific region.

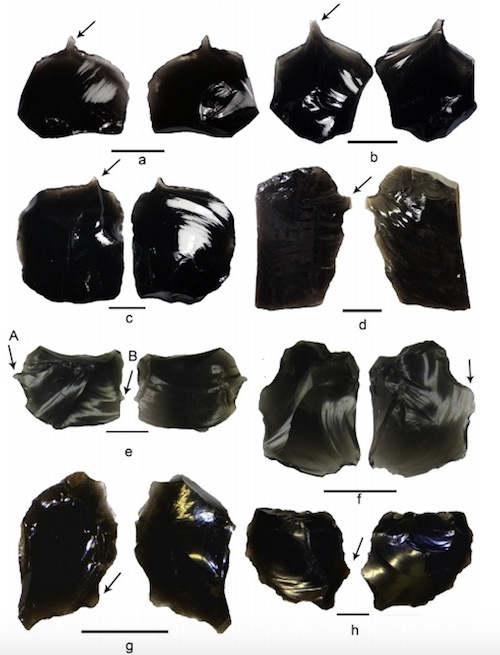

It’s unusual to discover any tools or artifacts used for tattooing, mostly because the implements used in ancient tattooing are usually made of perishable materials. On the archaeological site of Nanggu, however, researchers have found 15 separate obsidian artifacts that were used for tattoo artistry. The tools are at least 3,000 years old, and they all are shaped to perfect, short, sharp points.

They had originally thought the tools had been used by the islanders as awls to make clothes from skins and hides of native animals. The only trouble with that theory was the lack of large animals in the Solomon islands that we know the islanders actually hunted for their skins. We know from previous research that possum and lizard were popular for drum-making, but the islanders wouldn’t need complex obsidian tools for such work. The only work involved with these skins was removal of the tail and head.

Obsidian tools would have been very valuable, and probably not used for something as mundane as making clothing. Other contemporary cultures that had access to volcanic glass used it for blood-letting rituals. It’s likely that the tools were used for something important.

The ancient settlers of Oceania held tattooing in very high regard. Body decoration was an important cultural tradition, and it still is on these islands today. Tattoos could represent a person’s status in the tribe, or their relation to the spirits or gods. It seems likely that they would have created important tools for this equally important cultural tradition.

In order to test how likely the theory that these 15 obsidian tools were used for tattooing, the scientists began a set of experiments in 2015. They did 26 of these experiments over the course of four months, creating tattoos on pigskin (a good substitute for human skin), using the sort of resources these ancient islanders would have had available. They used black charcoal pigment, red ochre dye, and obsidian tools that were perfect mimics for the artifacts unearthed at Nanggu.

Once the experiments were done and the tattoos successfully created, the archaeologists and researchers compared the copycat obsidian tools with the 15 tools found at Nanggu. Both tools exhibited similar signs of wear and tear. Both had edges that were starting to become round and blunt. Both had thin scratches and microscopic chipping. To put a nail in the metaphorical coffin, the scientists tested the artifacts from Nanggu and found blood, charcoal, and ochre residue.

It does seem, then, that the tribes on the Solomon Islands, at least the ones that lived at Nanggu three-thousand years ago, used specially crafted obsidian tools for tattooing.

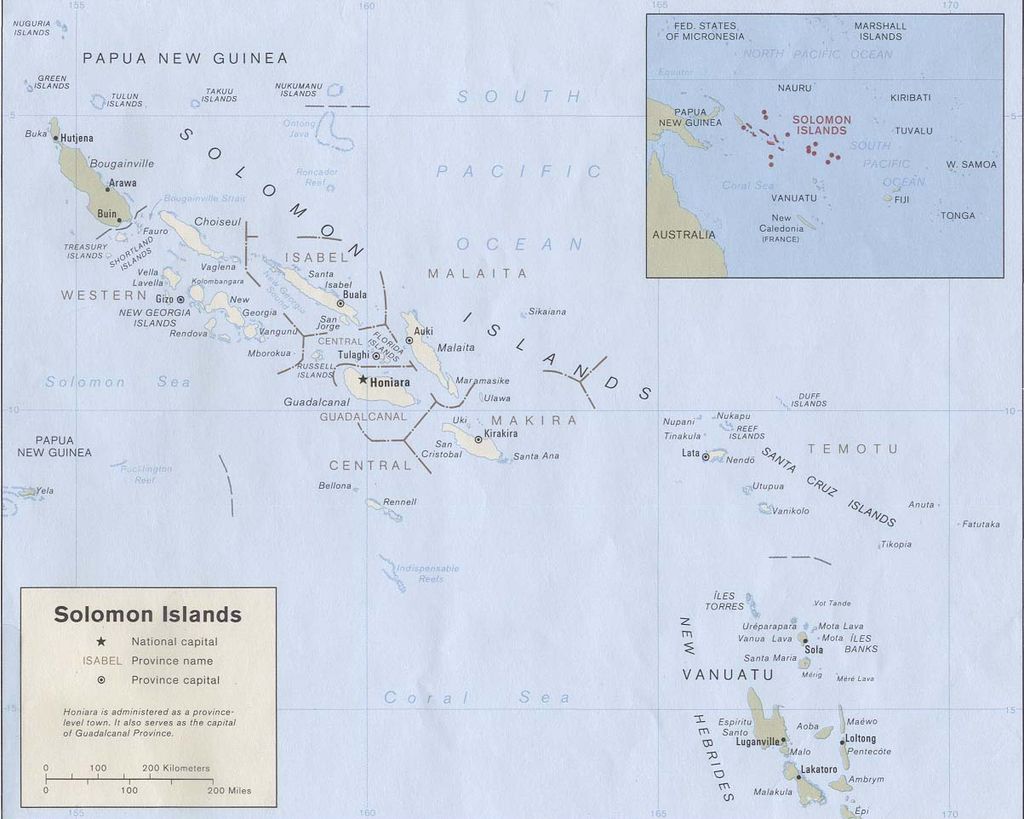

The first Papuan-speaking settlers arrived on the Solomon Islands sometime around 30,000 BC. Later, in 4000 BC, Austronesian speakers arrived on the islands, bringing with them new technologies such as outrigger canoes. The islands have their own distinctive ceramics and rich cultures, and didn’t come into contact with any Europeans until about 1568.

The site at Nanggu has proved to be invaluable in understanding the cultural history of the island nations of the Pacific. Each island has its own, rich cultural heritage that is slowly being uncovered through the careful work of archaeologists like the ones working on this site.

Nanggu will continue to be worked on by archaeologists from the Australian Museum and the University of Auckland in New Zealand. The archaeologists who worked on this site, Robin Torrence and Peter Sheppard, published their finds about the obsidian tools in the August issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science.

“The research demonstrates the antiquity and significance of human body decoration by tattooing as a cultural tradition amongst the earliest settlers of Oceania.” – Archaeologist Robin Torrence