Born Araminta Ross, Harriet Tubman is a famous abolitionist, humanitarian, and American Civil War spy. She was born into slavery, but was eventually able to escape. She would make thirteen missions to help seventy different enslaved families using the Underground Railroad. Tubman first worked as a cook and nurse during the Civil War, but later became armed as a scout and spy. She was the first women to lead an expedition armed. Later in life, she also grew very involved with the women’s suffrage movement.

Sometime between 1855-25, the exact date unknown, Araminta “Minty” Ross was born to slaves Ben Ross, who was owned by Anthony Thompson, and Harriet “Rit” Green, who was owned by Mary Pattison Brodess. Minty was the fifth of nine children. Rit, their mother, worked hard and struggled to keep the family together because slavery was a threat to families. It was not uncommon for families to be split up from being bought by new owners or for other reasons. When a trader from Georgia tried to buy their youngest child, Moses, Rit hid him for a month before confronting Brodess. Brodess and the trader tried to take the child, but Rit threatened them, and they backed off.

Growing up, Tubman would often have to take care of her younger siblings because her mother was too busy. It was very common for older siblings to take care of their younger ones in large families that were enslaved. Around five or six years old, Brodess had her work as a nursemaid for “Miss Susan”. If the baby woke up and began to cry, Tubman would be whipped for it. One day, she was even given five lashes just before breakfast, and the scars stayed for the rest of her life. To protect herself, she began wearing thicker clothes and fighting back, even running away for five days at one point. While checking muskrat traps in marshes for a planter named James Cook, Tubman came in contact with measles. Cook had to eventually send her back to the Brodess household so Rit could nurse her back to health. When she was healthy again, Brodess hired her out, and Tubman was constantly homesick and wanted to return to her mother and siblings. Slaveowners would often beat her and treat her very poorly. She was assigned to field and forest work, driving oxen, plowing, and hauling logs once she was old and strong enough to carry out these tasks.

As an adolescent, Tubman suffered through a terrible head injury. She was sent by her master to retrieve supplies from a dry-goods store when she encountered a slave that had left his owners fields without obtaining permission. The owner asked Tubman to help him to restrain the slave, but she refused. The slave ran away, and his overseer threw a heavy weight at him that instead struck Tubman on the head. She was bleeding and had fallen unconscious, but believed that her hair, which she had never combed before, saved her life. For two days, Tubman stayed at her owner’s house, but never received medical care. She was then sent back to the fields but was unable to work properly from the injury, and was sent back to Brodess. Brodess tried to sell her, but was unable to. Tubman soon began having terrible seizures that would leave her unconscious. These seizures continued for the rest of her life.

John Tubman, a free black man, and Araminta married around 1844, though she was still a slave. Shortly after their marriage, she switched her name to Harriet. Because any child born to an enslaved mother would be a slave, they did not have any children. Historians have suggested that John Tubman planned to help her buy her way out of slavery.

After falling ill once again in 1849, Edward Brodess attempted to sell her because it made her value as a slave go down. This made Tubman angry, and she prayed that God would change her owner’s ways. When Brodess was about to make a successful sale, she prayed that instead of changing his personality, that he would die for having such a terrible heart. About a week later, he died. His wife, Eliza, tried to sell off the slaves to pay off debts. Along with her brothers Ben and Henry, Tubman escaped slavery on September 17, 1849 after her owner had hired her out to a large plantation owner, Dr. Anthony Thompson. Two weeks later, Eliza realized they had escaped and posted a notice, scaring Ben and Henry. They decided to return to Brodess, and their sister was forced to go with them. Tubman quickly escaped after though, and left her brothers behind this time. It is unknown what route she took exactly, but she did use the Underground Railroad, which would later become an important part of her life. She traveled from Maryland to Philadelphia, where she began to work odd jobs to make money.

Tubman’s identity remained unknown as she made missions to help slaves. In December of 1850, she assisted her niece Kessiah and her two young children. Kessiah and her children were put up for auction, and were bought by John Bowley, Kessiah’s free husband. Tubman helped the family escape to Philadelphia that night. During the next spring, she began making trips to Maryland so she could help other family members escape slavery. Tubman helped her youngest brother, Moses, escape on her second trip to Maryland. She continued to make constant trips to help family members and friends via the Underground Railroad.

For the first time since she had escaped, Tubman returned to Dorchester County in the fall of 1851. She went to try and find her husband, but upon doing so, she found out he had married another woman, Caroline. Tubman had even saved up money she had made in Philadelphia to buy him a suit. When she tried to get him to join her, John refused, making her angry and upset. So, Tubman suppressed her anger and stopped herself from making a scene, and instead helped some local slaves escape to Philadelphia.

With the Fugitive Slave Law being in place, the Northern U.S. was dangerous for escaped slaves. Escaped slaves began making their way to Southern Ontario, where it was much safer. Tubman helped a group of eleven unidentified slaves escape to Ontario. Evidence from Frederick Douglass’s third autobiography suggests that Tubman stopped at his house with the group of escaped slaves. The two of them admired each other greatly, as they were both escaped slaves and active abolitionists.

Over the course of eleven years, Tubman made about thirteen expeditions and helped 70+ slaves escape. She also gave instructions to about 50-60 different escaped slaves. Most of her work and guiding was done during the winter in hopes it would lessen the chances she and the group she was traveling with were caught. A few times she even came close to old masters and owners, but was able to disguise herself well enough to avoid being caught. After injuring her head as a child, she would often experience visions that she called “consulting with God”. From these visions, Tubman trusted God to keep her safe, one of the main reasons as to why she continued her trips. She also kept a revolver with her at all times to protect her from slave owners, and to keep slaves she was guiding from turning around so they wouldn’t expose the group. William Lloyd Garrison nicknamed her “Moses” for all her hard work, despite the fact that she kept her identity closely guarded and hidden.

John Brown was introduced to Tubman in April 1858. Brown began to recruit supporters to attack slaveholders, and she joined his cause, though she did not believe violence was the way to go. He nicknamed her “General Tubman”. Tubman’s knowledge of the support networks that ran between Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Delaware were very valuable to him and his planners. Brown asked her to gather escaped slaves she knew to help him fight slaveowners, so she did. She also aided him when he began to make plans on raiding Harpers Ferry, Virginia in May of 1858. During this time, Tubman was also busy traveling to give abolitionist speeches and helping out relatives. She was not present at the time of Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry for unknown reasons, though historians have speculated many reasons why. That December, a month after the raid, Brown had been convicted of treason and hanged. Tubman praised him greatly afterwards, saying he got much more done just by dying then most do in their lifetime.

Earlier in 1859, Tubman had purchased a piece of small land just outside of Auburn, New York. Auburn was a very active city in the abolitionist movement, and here Tubman was able to get her parents to safety and away from the harsh winters in Canada. She continued to allow relatives and friends to stay at her home in Auburn, and it was seen as a haven. Tubman made it known to other escaped slaves and blacks that her home was always open if they needed a place to stay. Also, Tubman returned to Maryland to bring her niece Margaret to Auburn. Margaret’s daughter, Alice, would later call Tubman a kidnapper from taking Margaret from a good home to somewhere where no one was able to constantly take care of her. Because the identity of her parents was unknown, some biographers have said that it is possible that Margaret was actually Tubman’s daughter. There is no evidence of this, however, the two shared a very strong bond and even closely resembled each other. Tubman then conducted her last mission a year later in November of 1860 to help her sister and her two children escape. However, Tubman learned that Rachel, her sister, had died and she would have to pay a $30 to retrieve her children. Because she had no money at that point, the children had to remain enslaved. Tubman was able to take a group of escaped slaves to Auburn after a long, harsh trip from Maryland to Auburn.

In 1861, the American Civil War broke out. Tubman joined a group of abolitionists from Boston and Philadelphia that were on their way to South Carolina. She greatly hoped for a Union victory because it would make the country closer to abolishing slavery. While in South Carolina, Tubman assisted fugitives and escaped slaves, especially while in Port Royal. Tubman also served as a nurse while there, and rumours that she was blessed by God started up again when she did not come in contact with smallpox herself after treating many men who had. She disagreed with President Abraham Lincoln when he spoke of not abolishing slavery in the U.S. completely.

Lincoln issue the Emancipation Proclamation during January of 1863, which Tubman found as a very important step towards officially abolishing slavery. Not long after, she began leading a band of scouts through the land near Port Royal. With her group, she mapped unfamiliar land and reconnoitered the inhabitants. Afterwards, Tubman aided Colonel James Montgomery and informed him of key intelligence that helped him capture Jacksonville, Florida.

Tubman became the first woman to lead an assault during the Civil War Armed in June of 1863. The Raid at Combahee Ferry lasted from June 1-2 and was a successful Union victory. They were able to rescue over 750 slaves. Tubman was praised greatly for her success after the raid and continued to work for the Union for two more years. She would tend to free and escaped slaves and scout Confederate territory, and would later nurse wounded soldiers in Virginia. In April 1865 after the Confederacy surrendered to the Union, Tubman returned to her home in Auburn. On a train ride to New York, she broke her arm after and suffered from a few other injuries she refused the conductor’s orders to go to the smoking car because of her race. Two other passengers and the conductor grabbed her and threw her into the smoking car while white passengers jeered at her and told the conductor to kick her off.

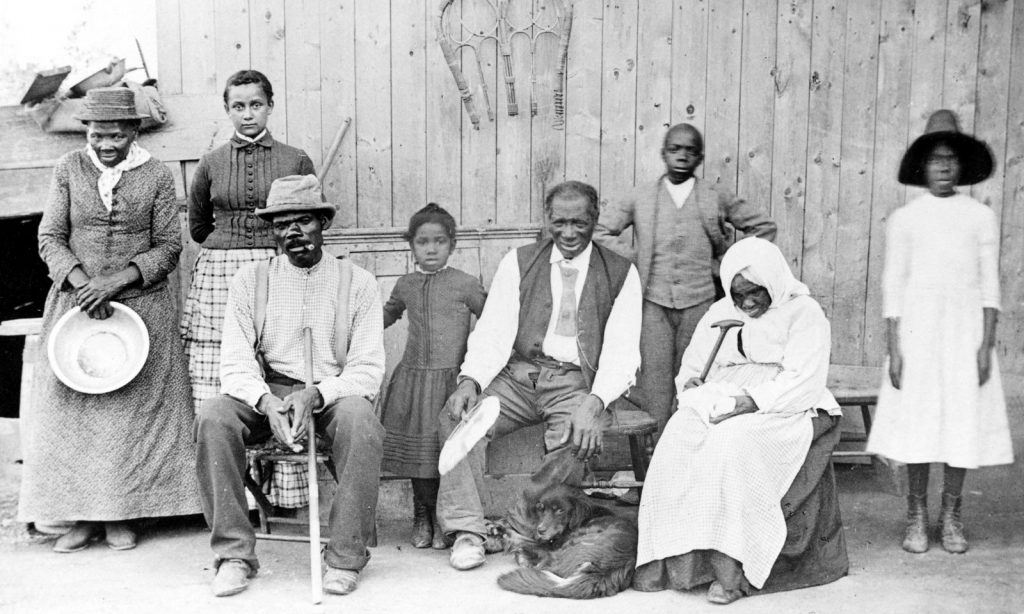

Because the government never compensated her for her work during the war until 1899, Tubman lived in a state of poverty. She spent the rest of her life in Auburn where she continued to help out her family and other blacks who were in need of it. To help pay the bills, she also took in boarders. Nelson Davis, a civil war veteran, was boarding at her home when the two fell in love. He was twenty-two years younger, but that did not stop them from getting married. On March 18, 1869, the two wed and would spend the next twenty years together. The couple adopted a baby girl in 1874 named Gertie. Davis died in 1888, and she would not follow until about twenty-five years later.

Friend of Tubman’s began raising funds to help her out financially. Sarah hopkins Bradford also wrote and published Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman in 1869, which made Tubman about $1,200. In 1886, Bradford published another biography on Tubman to help her out of poverty. Tubman was once attacked in 1873 by John Thomas and a man named Stevenson who claimed to sell her gold they had smuggled out of South Carolina. They knocked her out with chloroform, gagged her, stole her purse, and took the money she had borrowed from a wealthy friend to pay for the gold. Her family soon found her injured in the woods. When word got around about the incident, Congressmen Clinton D. MacDougall of New York and Gerry W. Hazelton of Wisconsin tried to pass a bill that would give Tubman $2,000 for her work in the war. However, the bill was not passed, and she was not given the money.

Beginning to work with the woman’s suffrage movement later in her life, Tubman worked alongside famous suffragists such as Susan B. Anthony and Emily Howland. She traveled across the country to large cities such as New York, Boston, and Washington D.C. to give speeches on women’s voting rights. In 1896, Tubman was the keynote speaker for the newly established National Federation of Afro-American Women. The press continued to praise and admire her for all she did.

In 1903, Tubman gave a piece of land to the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church located in Auburn. The land was supposed to be used as a home for older colored and native people. Five years later, the home opened and required a $100 entrance free. This angered Tubman, who said that people should not have to pay anything to stay at the home. When the Harriet Tubman Home for the Aged opened on June 23, 1908, despite being angry with how it was run, she was the guest of honor. Today, the home is now a U.S. National Historic Landmark along with her former residence and the the church.

Tubman began experiencing bad seizures and headaches as she grew older. In the late 1890s, she had undergone brain surgery in Boston. She had not taken any anesthesia during the surgery, but did what she had observed soldiers do when their limbs were amputated, bite down on a bullet. Her health and body were so frail by 1911, that she was admitted into the Harriet Tubman Home for the Aged. A newspaper had written about this, saying she was ill and had no money. The newspaper also began promoting people to give Tubman donations to help her financially.

On March 10, 1913, Harriet Tubman, at about ninety years old, died in Auburn, New York of pneumonia with relatives and friends surrounding her. She was buried in Auburn at Fort Hill Cemetery with semi-military honors.