Up until the Nineteenth Amendment was passed in 1920, women were unable to vote. After decades of women’s suffragists fighting for their rights, they were finally given them. First introduced in 1878, it was not approved by Congress until 1919. Within just over a year, Tennessee became the final state to ratify the amendment for it to be passed on August 18, 1920. In all, forty-eight states ratified the amendment, Hawaii and Alaska unable to because they were not apart of the union at the time.

From the time the United States was founded in the late 1700s, women did not share the same right as men. They were not allowed to vote and married women did not have the rights to own property. Instead of politics, women were believed to be focused on getting married, having children, and managing their households.

Women across the country had been wanting the rights to vote for quite some time before the campaign rose to a national level when famed suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott organized the Seneca Falls Convention on July 19-20, 1848. Though mainly women were in attendance of the convention, there were a few men, such as the notable former slave Frederick Douglass, making up over 300 people. Women at the convention mostly held the same beliefs: they should have better education and employment opportunities and deserved to be treated equally, such as having more political rights. Led by Stanton, the women at the convention wrote the “Declaration of Sentiments”, based off the Declaration of Independence. While in the latter, it was stated that all men were created equal, but both men and women in the former. In the declaration, it was stated that women also should be permitted the rights to vote, like men.

The press began to mock the convention once it ended after two days. This caused many delegates to withdraw their support of the declaration and women’s voting rights, all because the press, made up mainly by men, mocked them. Stanton and Mott stayed loyal to the cause persisting that they keep moving forward and organize more conferences for women’s rights. Susan B. Anthony, among many other suffragists, joined their cause as they worked hard to gain their rights as well.

For quite some time, the suffrage movement became very popular, but slowed down when the Civil War started until it’s end in 1865, of course also put aside by many as reconstruction began. Many women, though still strong believers in the women’s movement, were busy during the war while the country, now divided into two, fought for and against slavery. Black men gaining their rights to vote was a very controversial cause following the war as well, which many women’s suffragists also advocated for. Though Stanton, among others, did not agree with the 15th Amendment because it did not give women of any racial ethnicity to vote, but gave the right to all black men.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton formed the National Woman Suffrage Association, or just NWSA, along with fellow activist Susan B. Anthony in 1869. The American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), was formed by the married couple Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell. The two had been married since 1855 at that point, the two having a private agreement that gave them both similar rights during their marriage. At the ceremony, he had even pledged to never subject to the laws making husbands superior to their wives. In 1870, the couple also began the Woman’s Journal. The AWSA held beliefs that for women to gain voting rights, each state would have to pass amendments to their own constitution’s, granting women these rights. The NWSA and AWSA were constantly divided, though both working towards the same thing.

For the first time, women were granted voting rights in 1869 in the Wyoming Territory to residents twenty-one years of age and older. Once it became a state in 1890, women did not lose that right. For all suffragists, no matter if they always agreed or not, this was considered to be a huge victory.

The NWSA joined with the rest of the suffragist movement in 1878 to try and lobby Congress to make an amendment to the constitution granting women voting rights. In response, committees in both the House and Senate were formed so they could debate the proposal and issue. In 1866, the proposal eventually reached the Senate floor for voting. However, the amendment ended up being defeated.

Coming together in 1890, the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was formed by the combining of the NWSA and AWSA. The goal was to lobby in each state for women’s voting rights and within six years, they had already succeeded in Colorado, Utah, and Idaho. Each state had adopted new amendments to their constitutions and gave women residents the right to finally vote. As both Stanton and Anthony were becoming older and no longer able to run the NASWA, Carrie Chapman Catt took over to lead the organization.

Once again, the woman’s suffrage cause was given more momentum as it had in earlier years as the 1890s faded into the 1900s. The cause’s two more prominent and first leaders, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, passed away in 1902 and 1906. Their deaths were setbacks for the suffragists, but they kept moving forward with Catt at the head. She was successful in gaining voting rights for women in many different states all in the span of eight years, from 1910 to 1918: Washington, California, Arizona, Kansas, Oregon, the Alaska Territory, Montana, Nevada, New York, Michigan, Oklahoma, and South Dakota. Also, between 1913 and 1919, these state’s gave women rights to vote, but only in presidential elections: Illinois, Nebraska, Ohio, Indiana, North Dakota, Rhode Island, Iowa, Maine, Minnesota, Missouri, Tennessee, and Wisconsin.

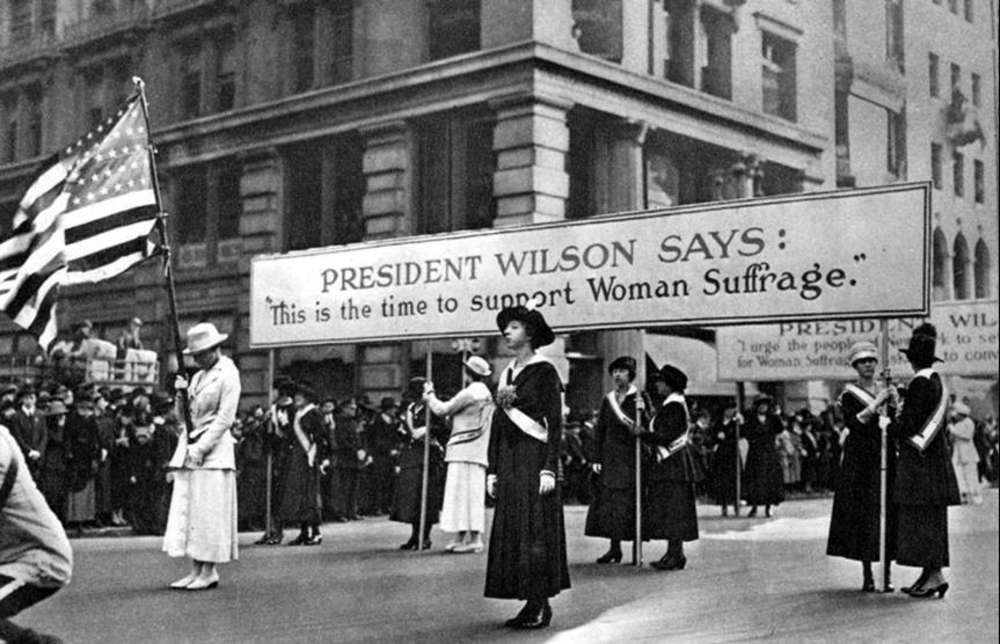

Harriot Stanton Blatch, the daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, began organizing marches, parades, and pickets to raise awareness for their cause around the same time with the Equality League of Self-Supporting Women, which later became known as the Women’s Political Union. With these strategies, there was constant unrest in Washington, D.C. for women’s suffrage. Hundreds of women ended up injured during a huge parade for suffragists in D.C. the night before President Woodrow Wilson was inaugurated in 1913.

Alice Paul formed the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage in 1913 as well. This organization later became known as the National Woman’s Party. As a matter of fact, some of the members of Paul’s group served time in jail because of their constant actions, such as picketing the White House on a regular basis and going through with many other staged demonstrations.

Originally not supportive of the cause, President Woodrow Wilson switched his views in 1918 because of Catt’s more subtle and harmless influences, unlike the efforts of Alice Paul. From then on, he became a supporter of women’s suffrage. With The Great War (World War I) coming to an end that same year, he tied in a proposed amendment for women’s voting rights along with the country being involved in the war. Wilson made sure to address the Senate when it was time to vote for the amendment, showing just how much he had come to support the cause. According to the New York Times article published on October 1, 1918, Wilson said:

I regard the extension of suffrage to women as vitally essential to the successful prosecution of the great war of humanity in which we are engaged.

By two votes, the amendment did not make it through the Senate. Women were so close to finally getting the vote, nearly having enough votes. The next year, however, Congress tried once more to get the amendment through.

Illinois Republican and U.S. Representative, James R. Mann, proposed that the house approve the Susan Anthony Amendment, which gave women the rights to vote, on May 21, 1919. Mann was also the chairman of the Suffrage Committee, a firm believer in the cause. The House passed the majority two-thirds votes needed by forty-two, having 304 votes for and 89 against it overall.

Luckily, the Senate also surpassed the two-thirds majority only two weeks later on June 4, 1919, with a vote of 56-25 (two more than the required number). From there, two-thirds of the states needed to ratify the amendment, and then, women would finally be able to vote!

Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin all ratified the amendment only six days after it was approved by the Senate. On June 16, 1919, Kansas, New York, and Ohio also ratified it. Pennsylvania ratified the amendment on Jul 24, 1919, Massachusetts the following day, and Texas on the twenty-eight. It hadn’t even been a month, and already, the amendment had nine states ratifying it.

Iowa and Missouri followed on the second and third of July, then Arkansas on July 28, 1919. Montana became the thirteenth state when they ratified the amendment on August 2, 1919, with Nebraska also doing so that same day. In September, Minnesota ratified it on the eighth, New Hampshire two days later. For October, Utah was the only one, having ratified the amendment on the second. California and Maine were next on the first and fifth of November, then North Dakota on December 1, 1919, with South Dakota three days later and Colorado on the fifteenth. In all, twenty-two states ratified the amendment before the end of 1919, and only fourteen more needed. Already, the amendment was more than halfway there to ratification.

Both Kentucky and Rhode Island ratified the amendment on January 6, 1920, Oregon close behind on the thirteenth then Indiana on the sixteenth. Wyoming was the last ratification that month on January 27, 1920. Nevada followed on February 7, 1920 then New Jersey two days later, and Idaho two days after that, Arizona the next day on February 12. New Mexico ratified the amendment on February 21 and the Oklahoma on February 28. In March, both West Virginia (March 10) and Washington (March 22) became the final few.

Lastly, Tennessee voted to ratify the amendment on August 18, 1920, making it officially legal for women to vote all over the country. After decades of hard work and attempts, suffragists finally reached their shares goal: women could vote. Many of the first prominent suffragists would never get to live to see the amendment passed and women rejoicing all across the country, but their hard work and determination was not for nothing.

Some for the first time, and some already having done so in their states, 8 million women all over the United States finally were able to vote for president on November 2, 1920, only a few months after the amendment’s ratification.

Connecticut (September, 1920), Vermont (February, 1921) Delaware (March, 1923), Maryland, (March, 1941), Virginia (February, 1952), Alabama (September, 1953), Florida (May, 1969), Georgia (February, 1970), Louisiana (June, 1970), North Carolina (May, 1971), and Mississippi (March, 1984), all eventually ratified the amendment as well. All but two states, Alaska and Hawaii ratified the amendment, as they had not been states upon the amendment’s ratification.

Now, Women’s Equality Day is celebrated every year on August 26, marking the day in 1920 when the 19th Amendment became certified as the law. Since 1972, every single president has issued proclamations on that very day.

Because of the hard work of not just the women, but also men, of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, women can now vote today. Notable suffragists included Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Lucretia Mott, Lucy Stone, Carrie Chapman Catt, Alice Paul, Ida B. Wells, and many others. Thanks to not only these women, but also many others, women’s suffrage is no longer just an idea and cause, it is a real thing in the United States.