They look similar because on the surface it is the same scene: a couple, a baby carriage, a public sidewalk, and the quiet question of who takes the handle. But in April 1925, when a New York newspaper feature called “The Inquiring Photographer” asked, “Who should push the baby carriage, husband or wife?”, that everyday moment carried far more weight than a casual stroller swap in a modern park.

In 1925 the baby carriage question was really about gender, class, and who counted as a modern man or woman. Today the same question still pops up, just with different language: “Is he an involved dad?” “Are chores split fairly?” By tracing the origins, methods, outcomes, and legacy of that 1925 street question and comparing it to how we talk about parenting now, you can see how much has changed and what stubbornly has not.

“Who should push the baby carriage?” was a 1920s way of asking who does the visible work of care. That same argument continues now in debates over emotional labor, mental load, and equal parenting.

Where did the 1925 baby carriage question come from?

Picture New York City on April 27, 1925. The Roaring Twenties are in full swing. Women have had the federal vote for less than five years. Flappers, bobbed hair, and short skirts are worrying parents and selling newspapers. In that climate, a seemingly harmless question about a baby carriage made perfect sense as a conversation starter.

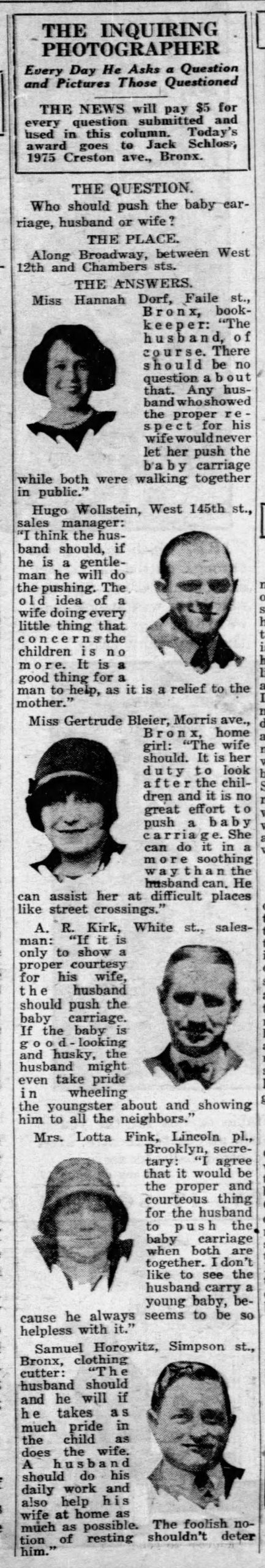

“The Inquiring Photographer” was a regular feature in several New York papers in the 1910s and 1920s. A staff photographer and reporter would roam the streets, ask passersby a single question, snap their picture, and print a handful of answers the next day. It was early clickbait, just on cheap newsprint instead of a phone screen.

On April 27, 1925, the prompt was: “Who should push the baby carriage, husband or wife?” The paper knew exactly what it was doing. Baby carriages were everywhere in growing cities. They were visible symbols of domestic life spilling into public space. And the 1920s were full of anxiety about whether women were abandoning motherhood for jazz clubs and offices, and whether men were too soft or too hard.

In the late 19th century, respectable middle-class women often pushed prams as a kind of public proof of domestic virtue. Working-class women used them too, but less as a symbol and more as a practical way to move children and groceries. Men pushing prams did exist, but it was unusual enough to draw comment or jokes.

By 1925, that older Victorian ideal of the angelic mother at home was colliding with a new image: the modern girl who smoked, danced, and sometimes worked for wages. Newspapers fed on that tension. A question about who should push the carriage let readers argue about whether modern men should help more at home, or whether that was unmanly.

So the origin of the 1925 question was not random curiosity. It grew out of a media culture that used street interviews to poke at gender roles during a period of rapid social change.

This matters because it shows that even a simple question about a stroller was shaped by the anxieties of its time, not by some timeless rule about who is “naturally” meant to care for children.

What methods did 1920s media use vs today’s debates?

The “Inquiring Photographer” method was simple and theatrical. A reporter picked a question, walked up to strangers, and asked for a quote. The photographer captured their faces. The next day, a handful of answers ran under their portraits. It was curated public opinion, filtered through an editor’s sense of what would amuse or provoke readers.

We do something similar now, just with different tools. Reddit threads, Instagram polls, and TikTok duets collect quick-hit opinions on parenting and gender. Instead of one photographer on a Manhattan sidewalk, you get thousands of people arguing in comments about whether a dad pushing a stroller is “bare minimum” or “such a good father.”

In 1925, the question itself was framed as either/or: husband or wife. Someone had to be the default pusher. The reporter did not ask, “Should parents share childcare?” That idea existed in some families, but it was not the way mass media framed the issue.

Today, the method and the framing are different. Surveys by organizations like the Pew Research Center ask about “time spent on childcare” or “sharing household responsibilities.” Social media posts talk about “involved fathers” and “equal partners.” The language is more about balance and fairness, less about who looks silly behind a pram.

There is also a class angle in both eras. In 1925, the people stopped on the street for a photo were often white, decently dressed, and available in the middle of the day. That skewed whose opinions got printed. Working-class parents who left babies with relatives or older siblings while they worked might not appear in the feature at all.

Today, the loudest online debates about baby-carrying and chore charts tend to come from people with some disposable time and access to smartphones. Nannies, grandparents, and shift workers who handle a lot of actual childcare are less visible in those conversations.

So the method in both eras selects for a certain slice of the population and then presents that slice as “what people think.” The 1925 photographer did it with a camera and a column. We do it with upvotes and algorithms.

This matters because it reminds us that public debates about parenting and gender are shaped by who gets asked and who gets heard, not just by what families are actually doing at home.

What were the expected outcomes in 1925 vs the realities now?

When the 1925 question went to print, most readers would have assumed a default answer: the wife. Middle-class American culture still expected women to be primary caregivers. Men were supposed to earn the wage, women to raise the children and keep the home. A husband pushing a carriage might be praised as considerate, or teased as henpecked.

Etiquette books and advice columns of the 1910s and 1920s often reinforced that split. A “good” mother was attentive, patient, and largely home-based. A “good” father was protective and financially reliable. The baby carriage was part of the mother’s toolkit, like the kitchen and the laundry line. It was not a standard prop in the image of respectable masculinity.

That did not mean men never pushed prams. Photographs from the 1910s and 1920s show fathers doing exactly that, especially on weekends or holidays. But it was framed as an exception or a charming scene, not the baseline expectation. The newspaper’s question worked precisely because it played with that tension: is it right or wrong for a man to take over this visible symbol of mothering?

Fast forward a century and the expected outcome has shifted. In many Western countries, surveys show that fathers spend more time on childcare than their grandfathers did. Pushing a stroller is now part of the standard image of a “modern dad.” Advertisements feature bearded men with baby carriers and coffee cups. A man with a pram is less likely to be mocked than to be praised for doing what used to be called “women’s work.”

Yet the reality behind the photo is more complicated. Studies in the United States and Europe still find that mothers do more unpaid childcare and housework than fathers, even in dual-income households. Sociologists call the planning and remembering side of this work the “mental load.” Who buys diapers, schedules pediatric visits, and keeps track of nap times often matters more than who physically pushes the stroller on a Sunday walk.

So if you asked the 1925 question today, the most common public answer might be, “Both parents should push the baby carriage.” But the private reality in many homes is that the mother still handles more of the daily grind, even when the father is proudly pushing the pram in public.

This matters because it shows that visible gestures of equality can change faster than the underlying division of labor, and the baby carriage is a good example of that gap.

How did class and technology shape who pushed the carriage?

The 1925 question also hides a blunt fact: not every family had a baby carriage, and not every mother or father had time for leisurely walks. Prams were more common in urban and suburban middle-class families. They cost money and took space. Poorer families might carry babies in arms, use slings, or leave infants at home with older siblings while parents worked.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the baby carriage itself had been a status symbol. In the 1870s and 1880s, ornate carriages with high wheels and fancy upholstery signaled that a family had a nurse or a mother who could spend time promenading. By the 1920s, mass production had made simpler carriages more affordable, but the association with respectability lingered.

Technology also shaped who pushed. Early carriages were heavy and awkward. Streets were rough. Getting a pram down a tenement staircase or across a muddy road was work. In that context, the person who stayed closer to home, usually the mother or a hired caregiver, did most of the pushing.

By the late 20th and early 21st centuries, strollers became lighter, foldable, and car-compatible. Travel systems, jogging strollers, and baby carriers changed the physical experience of moving with a baby. It became easier for a parent to combine commuting, errands, and childcare. That made it simpler for fathers to integrate stroller-pushing into their daily routines, especially in cities with good sidewalks and parks.

Class still matters. High-end strollers can cost as much as a used car. In many places, grandparents, older siblings, or paid caregivers are the ones actually pushing. Yet media images and debates, both in 1925 and now, tend to center on a heterosexual couple deciding who takes the handle.

Technology and class shaped who could be seen as a “proper” stroller pusher in public. That was true in 1925 and it is still true today, just with different brands and price tags.

This matters because it reminds us that when we argue about gender roles using the baby carriage as a symbol, we are often talking about a relatively narrow slice of families, not everyone raising children.

What legacy did that 1925 question leave for modern parenting debates?

The 1925 “Inquiring Photographer” feature is a small artifact. It is one day’s question in one city. Yet it captures a moment when ordinary people were being asked to comment publicly on gender roles, and their answers were being packaged as entertainment.

That pattern never really went away. Today’s viral posts about “dads at the playground” or “who gets up at night” are direct descendants of that street-corner question. They turn private negotiations inside a household into public content, then invite strangers to weigh in on who is right.

The legacy is visible in language too. In 1925, the debate was framed as husband versus wife. In the late 20th century, it shifted to “working mother” versus “stay-at-home mom,” as if fathers were not also making choices about work and care. In the 21st century, the conversation has started to include same-sex couples, single parents, and non-binary parents, which complicates the old husband/wife framing completely.

Yet the core question lingers: who is expected to do the visible and invisible work of raising children, and what does that say about what we think men and women are for?

Historians looking back at items like the 1925 baby carriage question use them as barometers. They show what could be joked about, what felt controversial, and what seemed so obvious it did not need asking. The fact that a newspaper could treat “husband or wife” as a real question in 1925 tells you that some people were already seeing men push prams and wondering if that was the future.

Today, a similar barometer might be a meme about a dad wearing a baby in a carrier at the grocery store. Is the tone mocking, admiring, or matter-of-fact? The answer tells you where a culture is on the long road from “helping out” to “equal parent.”

This matters because it shows that the way we talk about small acts of care, like pushing a stroller, is one of the clearest windows into how we understand gender, work, and family.

Why does a 1925 pram question still matter now?

If you strip away the flapper dresses and the rattling streetcars, the 1925 baby carriage question and today’s parenting debates share the same skeleton. Both ask who should take on the routine, sometimes tedious, often joyful work of caring for children in public view.

The 1925 answer was shaped by a world where men’s and women’s roles were legally and socially distinct. The modern answer is shaped by a world where laws have changed, but habits and expectations lag. The stroller has gone from a symbol of maternal duty to a prop in Instagram posts about “dad life,” yet the unequal mental load many mothers describe suggests that the deeper shift is unfinished.

Looking back at that Inquiring Photographer question helps cut through nostalgia. There was never a golden age when everyone agreed on who should push the pram. It was argued over on sidewalks and in newspapers then, just as it is argued over in comment sections now.

The legacy is not the specific answers people gave in 1925. We do not have a neat tally of “husband” versus “wife.” The legacy is the fact that a simple act like pushing a baby carriage could become a public referendum on what kind of man or woman you were. That pressure still hangs over parents today, even if the fashions and the strollers have changed.

So when you see that 1925 question resurface on Reddit a century later, it is not just a quaint curiosity. It is a reminder that the politics of care have always been visible on the sidewalk, one baby carriage at a time.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who usually pushed the baby carriage in the 1920s?

In the 1920s, especially in middle-class families, mothers or hired caregivers usually pushed the baby carriage. Fathers did push prams at times, but it was seen as unusual enough to attract comment or praise rather than the default expectation.

What was the Inquiring Photographer in 1920s newspapers?

The Inquiring Photographer was a recurring newspaper feature where a photographer and reporter asked random people on the street a single question, took their photos, and printed a selection of answers. It was an early form of public-opinion entertainment, similar in spirit to modern street interviews or social media polls.

How have gender roles in parenting changed since 1925?

Since 1925, legal and social barriers have eased, and fathers in many countries spend more time on childcare than earlier generations. Pushing a stroller is now part of the standard image of an involved dad. However, studies still show that mothers usually do more unpaid childcare and housework, including the planning and organizing often called the “mental load.”

Why did people care who pushed the baby carriage?

People cared who pushed the baby carriage because it symbolized deeper beliefs about gender roles and respectability. In 1925, a man pushing a pram could be seen as unusually considerate or unmanly, while a woman without children in public could be seen as neglecting her “duty.” The carriage made private family roles visible in public, which is why it was such a useful question for newspapers and remains a live issue in modern debates about equal parenting.