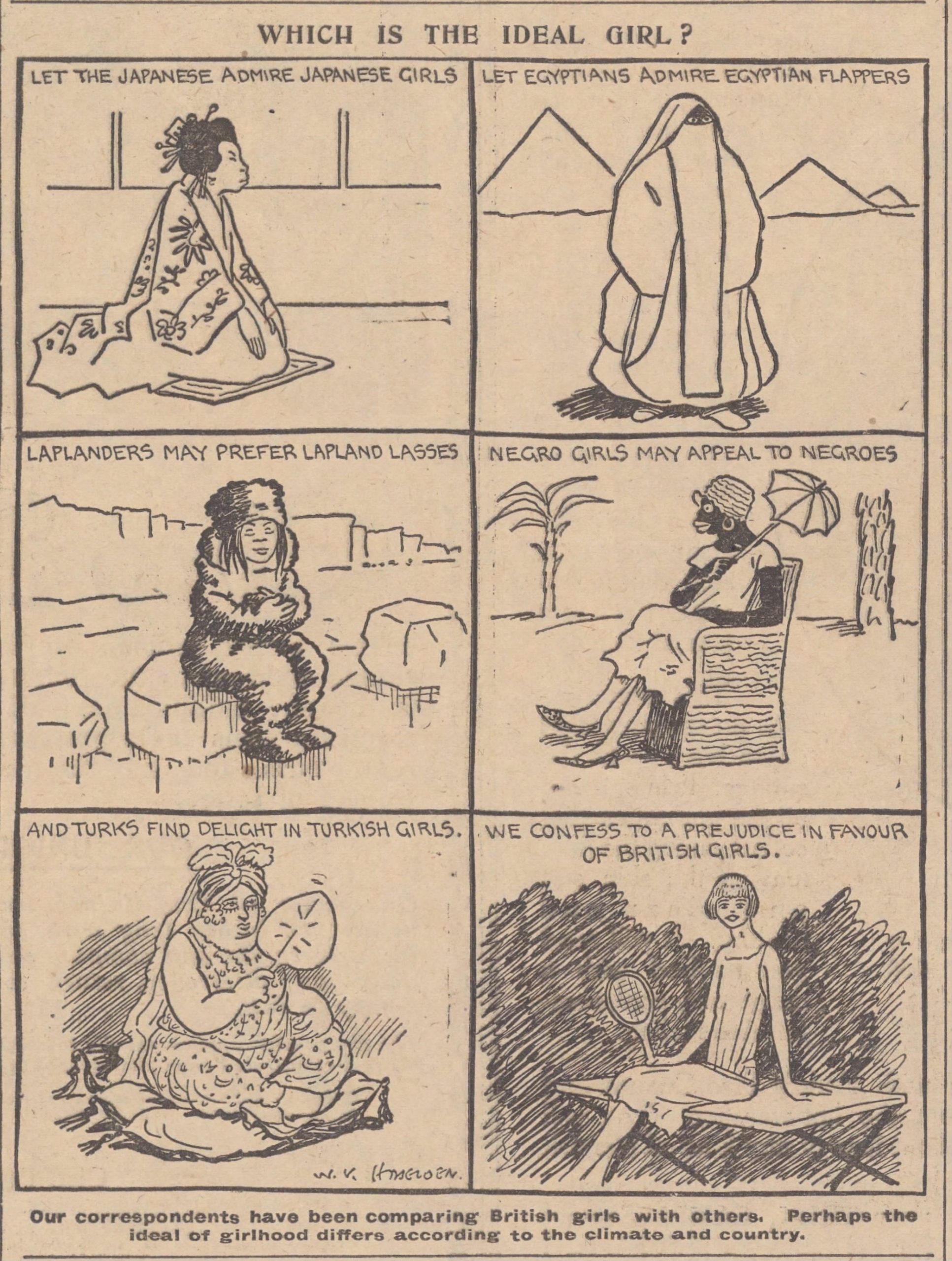

On a June morning in 1925, a reader unfolded the paper and found a strange little contest. A grid of women’s faces, numbered and neatly arranged, sat under the headline: “Which Is The Ideal Girl?” No article. No explanation. Just a prompt to judge.

That kind of feature was common in the 1920s. Newspapers and magazines ran beauty contests, photo spreads, and personality quizzes that invited readers to pick the “ideal” woman: the best face, the best figure, the best type for a wife. The June 10, 1925 clipping that resurfaced on Reddit is one of hundreds that once filled American papers.

So what was really going on? This was not just a silly quiz. It was a window into how the 1920s tried to define womanhood at a moment when women could finally vote, cut their hair, and work outside the home. By the end of this, you will see how a single newspaper page about the “ideal girl” connects to advertising, eugenics, Hollywood, and the way dating apps work today.

1. The “Ideal Girl” Quiz Was a Beauty Contest in Disguise

At its core, the 1925 “Which Is The Ideal Girl?” feature was a beauty contest flattened onto a page. Readers were asked to scan a set of faces and pick the one that best matched their idea of the perfect woman. No biographies. No voices. Just looks.

Newspapers had been running beauty contests since at least the 1910s. By the mid‑1920s, they were everywhere. The Atlantic City pageant that became Miss America began in 1921 as a “Fall Frolic” to extend the tourist season, with newspapers sending their “most beautiful” readers as contestants. Local papers from New York to Kansas City ran photo contests of “prettiest stenographer” or “best bathing beauty.”

The 1925 quiz fit that pattern. Editors loved these features because they were cheap filler and guaranteed reader engagement. Readers mailed in ballots or coupons. Some papers promised prizes. Others simply published the “winner” and congratulated the city for its taste.

A concrete example: in 1921, the Washington Times ran a “Most Beautiful Girl in Washington” contest. The winner, Margaret Gorman, went on to become the first Miss America. What started as a newspaper stunt turned into a national beauty standard with sponsors, judges, and rules about measurements and morality.

So what? The “ideal girl” quiz mattered because it normalized the idea that women’s public worth could be ranked and voted on by strangers, turning beauty contests into a routine part of daily media and setting the stage for national pageants and modern reality dating shows.

2. 1920s “Ideal Girl” Images Were Selling Whiteness and Respectability

When people today see the 1925 “ideal girl” image on Reddit, one question pops up fast: where are the women of color? The answer is blunt. In mainstream American papers of the 1920s, the “ideal girl” was almost always white, usually light‑skinned, and often described in coded racial terms like “Anglo‑Saxon” or “Nordic.”

The 1920s were the high tide of American eugenics and racial anxiety. Immigration laws like the Johnson‑Reed Act of 1924 restricted arrivals from southern and eastern Europe. Popular magazines ran pieces on “race betterment.” Beauty contests did quiet racial work. They presented a visual answer to the question: what does the “best” American woman look like?

Take the 1922 “Miss America” pageant. Contest rules required contestants to be “of good health and of the white race.” Black women were excluded outright. Newspapers that ran “ideal girl” or “perfect type” contests almost never featured nonwhite faces. When they did, it was often in segregated Black newspapers like the Chicago Defender or the Pittsburgh Courier, which ran their own beauty contests for Black readers.

Even within whiteness, there were hierarchies. Ads and articles praised “Nordic” blondes or “all‑American” brunettes with straight noses and slim figures. The silent film star Mary Pickford, with her curls and childlike face, was marketed as “America’s Sweetheart,” a kind of living “ideal girl” for the 1910s and early 1920s. By mid‑decade, the flapper type, embodied by actresses like Louise Brooks with her bobbed hair and slim body, became another version of the ideal.

So what? The 1925 quiz mattered because it helped fix a narrow, racialized image of female beauty as normal and desirable, quietly teaching readers that the “ideal” American woman was white and that everyone else was outside the frame.

3. The “Ideal Girl” Was Supposed to Be Modern but Still Obedient

On the surface, 1920s “ideal girl” features celebrated the new, modern woman. Short hair, shorter skirts, visible makeup. The flapper had arrived. Yet the way newspapers talked about the “ideal” woman kept circling back to old expectations: purity, domesticity, and obedience.

In 1925, women had only been voting in U.S. federal elections for five years. They were entering offices as typists, clerks, and secretaries. Some went to college. Some smoked and drank in public. Moralists complained about “petting parties” and jazz. The “ideal girl” quiz tried to tame this change by insisting that, beneath the bobbed hair, the perfect girl was still modest and marriage‑minded.

Advice columns and companion pieces to these quizzes spelled it out. A typical 1920s women’s magazine might run a feature titled “What Men Want in a Wife” alongside beauty photos. The answers rarely mentioned careers or independence. They praised “sweetness,” “cheerfulness,” “good housekeeping,” and “willingness to sacrifice.”

One example: in 1926, the Ladies’ Home Journal published a widely discussed piece about “The Girl He Will Marry.” It described an ideal bride who was neat, not too flashy, careful with money, and supportive of her husband’s career. She could bob her hair, but she should not be “fast.” The message was clear. You could look modern, but you could not act too free.

The “ideal girl” quizzes mirrored that tension visually. Faces might look up‑to‑date, but captions and commentary, when they appeared, stressed “good character,” “modest dress,” and “home training.” The ideal girl was allowed to be pretty and a little daring, yet she was still expected to fit into a traditional marriage.

So what? These quizzes mattered because they helped negotiate the terms of women’s new freedoms, offering a compromise image of a woman who could look modern while staying safely within old gender roles.

4. Newspapers Used “Ideal Girl” Contests to Hook Readers and Sell Ads

The “ideal girl” page was not just social commentary. It was a business strategy. Newspapers used contests and quizzes to boost circulation, collect reader data, and sell advertising space, especially to companies targeting women.

In the 1920s, advertisers realized that women controlled a large share of household spending. Soap, cosmetics, clothing, food, appliances. If you could get women to read your paper or magazine, you could sell that audience to advertisers. Beauty contests and “ideal girl” features were bait.

Many contests required readers to mail in coupons, vote, or submit photos. That created a list of engaged readers with addresses, ages, and sometimes occupations. Editors could brag to advertisers about their “active female readership.”

Look at the way the Atlantic City pageant evolved. By 1923, it had corporate sponsors. Newspapers promoted contestants. Cosmetic companies used winners in ads. The “ideal” girl’s face sold cold cream and shampoo. The same pattern played out on the page. A spread of “ideal” faces might share space with ads for Pond’s cold cream, Lux soap, or a new brand of lipstick.

A concrete example: in 1925, Pond’s ran a national campaign using “Pond’s girls,” real women whose photos appeared in magazines as examples of clear‑skinned beauty. The ads claimed that actresses and socialites used Pond’s to maintain their looks. The message tied a specific product to the broader idea of the ideal modern woman.

So what? The 1925 quiz mattered because it blurred the line between content and advertising, turning the “ideal girl” into a marketing tool and helping to build a consumer culture where women’s insecurities could be targeted and monetized.

5. The “Ideal Girl” Idea Helped Shape How We Judge People Today

Strip away the 1920s fonts and hairstyles, and the “Which Is The Ideal Girl?” page looks uncomfortably familiar. A grid of faces. Quick judgments. Ranking strangers by looks. It is not far from swiping on a dating app or voting on a reality show contestant.

The 1920s did not invent judging people by appearance, but they industrialized it. Cheap photography, mass‑circulation newspapers, and national advertising created a shared visual culture. People across the country saw the same faces and were told to agree on who was beautiful, who was modern, who was “ideal.”

Hollywood amplified this. Stars like Clara Bow, the original “It Girl,” became templates for desirability. Bow’s 1927 film “It” sold the idea that a certain mix of charm and sex appeal could vault a working‑class shop girl into romance with a rich boss. The movie did not cause the “ideal girl” quiz, but it swam in the same waters. Both assumed that looks and charm were tickets to a better life.

Today, people use algorithms instead of newspaper ballots, but the logic is similar. Dating apps present grids or stacks of faces. Users swipe left or right, often with minimal information. Social media rewards certain looks with likes and followers. Beauty pageants still exist, though they now share space with influencer culture.

One direct line: the Miss America pageant, born out of 1920s newspaper beauty contests, only dropped its swimsuit competition in 2018 after years of criticism. For nearly a century, the “ideal” American woman was literally judged in front of a panel and a national audience in a bathing suit. That tradition traces back to the same era that produced the 1925 newspaper quiz.

So what? The “ideal girl” page mattered because it helped normalize the idea that strangers could and should rate each other visually, a habit that still shapes modern dating, social media, and the pressure to match ever‑shifting beauty standards.

The 1925 “Which Is The Ideal Girl?” clipping looks quaint at first glance, a relic from a world of bobbed hair and print news. Underneath, it carries a lot of weight. It captured a moment when women were gaining rights but still being squeezed into narrow roles, when racial hierarchies were being quietly reinforced through images, and when media companies were learning how to turn beauty into data and profit.

That is why the image keeps circulating online. People sense that it is not just about old‑fashioned sexism. It is about how a society decides whose face belongs on the front page, whose body gets measured, and whose idea of the “ideal” counts. The 1925 quiz is gone, but the question it asked never really left.

Frequently Asked Questions

What was the 1925 “Which Is The Ideal Girl?” newspaper page?

It was a newspaper feature that showed a grid of women’s faces and asked readers to pick the “ideal” girl. It functioned as a beauty contest on paper, inviting the public to judge women based on appearance alone, often with ballots or coupons sent back to the paper.

Were women of color included in 1920s “ideal girl” or beauty contests?

In mainstream white newspapers and national pageants, women of color were usually excluded. Contest rules often required contestants to be white, and photo spreads of the “ideal” woman almost always showed white faces. Black newspapers ran their own contests, but those were separate from the dominant media image of the “ideal girl.”

How did 1920s beauty contests lead to Miss America?

Local newspaper beauty contests in the early 1920s sent winners to Atlantic City for a “Fall Frolic” event. In 1921, this became a national pageant, later called Miss America. The first winner, Margaret Gorman, had been chosen in a Washington newspaper contest, showing how print stunts evolved into a national institution.

How is the 1920s “ideal girl” idea similar to modern dating apps?

Both rely on quick visual judgments of strangers. The 1920s quiz asked readers to pick an “ideal” from a grid of faces. Dating apps present users with photos and minimal information, encouraging snap decisions about attractiveness. The technology changed, but the habit of ranking people by looks stayed very similar.