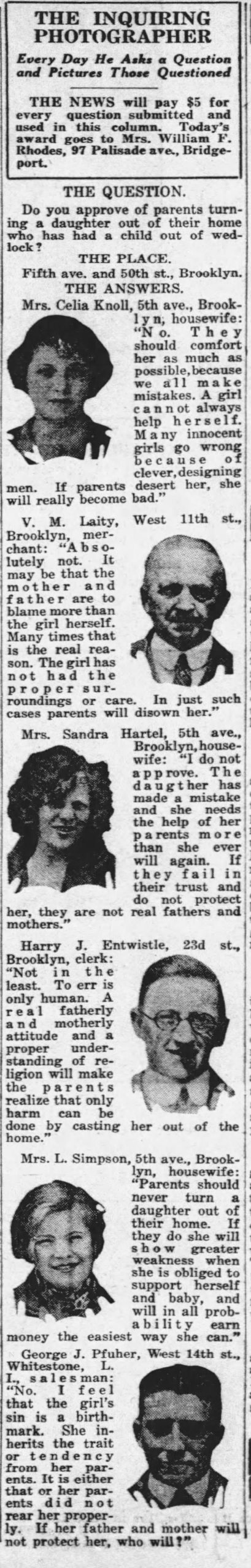

On June 5, 1925, a New York newspaper photographer walked the streets with a blunt question: “Do you approve of parents turning a daughter out of their home who has had a child out of wedlock?”

Strangers on sidewalks were being asked to judge a girl they would never meet. In the real 1920s, many families did throw daughters out. Others hid them in maternity homes, forced quick marriages, or sent the baby to adoption. Respectability mattered more than the girl’s future.

This was not a fringe issue. In the 1920s, an estimated 3 to 5 percent of all births in the United States were to unmarried women, and those births carried real social and economic punishment. “Illegitimacy” was a legal category that shaped inheritance, welfare, and even where a woman could live or work.

So what if Americans had answered that photographer differently? What if, in the mid‑1920s, the dominant response had been: “No. You keep your daughter, and you help her raise the child.”

Below are three grounded counterfactuals. Each asks: if attitudes toward unwed mothers had shifted in 1925, what would have changed for families, law, and culture? And which version of that alternate 1920s is actually plausible?

Why 1925 parents threw daughters out in the first place

To imagine different outcomes, you have to know what you are pushing against. In 1925, the phrase “child out of wedlock” did not just mean a family embarrassment. It meant legal disability and lifelong stigma.

Most U.S. states still had “illegitimacy” laws that limited a child’s right to inherit from the father. Many birth certificates were marked in ways that quietly branded the child. Churches, especially Catholic and many Protestant congregations, treated sex outside marriage as serious sin. Respectable middle‑class parents worried about their other children’s marriage prospects if a scandal broke.

Economics made everything harsher. There was no federal welfare state yet. Social Security did not exist. Aid to dependent children was only just emerging in a few states and was usually restricted to widows, not “fallen” women. A single mother without family support often had two bad options: low‑paid work that left no time for childcare, or surrendering the baby.

So when parents expelled a pregnant daughter, they were not just being cruel. They were protecting their own social standing and finances in a system that punished any deviation from the script of marriage first, children later.

This matters because any alternate 1925 where parents keep their daughters has to grapple with the same legal codes, churches, and pay scales. You cannot just flip a moral switch and get a Scandinavian welfare state.

Scenario 1: Quiet acceptance at home, no legal change

In the first counterfactual, imagine that the Inquiring Photographer’s question lands differently. Newspapers, advice columnists, and clergy start to frame expelling daughters as heartless, even unchristian. Public opinion shifts just enough that most parents keep their daughters and their grandchildren under the same roof.

Nothing big changes in law. “Illegitimacy” still exists as a legal category. Inheritance rules stay the same. Adoption agencies and maternity homes still operate. But at the family level, the script softens.

What would that look like in practice?

First, more three‑generation households. Instead of sending a pregnant girl away to a home for “wayward” women, many families would quietly keep her on. The grandparents might present the child as their own late‑in‑life baby or as a “niece” or “nephew.” This already happened in some families. In this scenario it becomes common rather than exceptional.

Second, less pressure for shotgun marriages. In the real 1920s, hurried weddings were often arranged to “legitimize” a pregnancy. If parents are more willing to keep their daughters, they have more leverage to refuse a bad match. The man might still be pushed to marry, but a girl’s survival would not depend on it as often.

Third, a small but real shift in work and schooling. If parents keep daughters at home, some will insist the girl finish high school or even attend a local teacher’s college while the grandparents help with childcare. That is easier in cities, where streetcars and jobs are nearby, than on isolated farms. You might see a modest uptick in single mothers with some education, which in turn slightly raises their earning power.

None of this erases shame. The daughter would still face gossip, and the child would still be legally disadvantaged. Many families would keep the pregnancy secret, send the girl away to give birth, then bring her back with a “new sibling.” But the raw brutality of being thrown into the street would be rarer.

So what? In this scenario, the main trajectory change is private. Fewer women are driven into prostitution or destitution, and more children grow up with some extended family support, but the legal and cultural category of “illegitimate child” survives mostly intact.

Scenario 2: A moral panic flips into reform

Now take a bolder path. In this version, a string of 1920s tragedies forces the issue into national politics.

Imagine a case that could have happened: a young woman in a respectable Midwestern town is expelled by her parents after giving birth. She and her baby die of exposure or suicide. A local reporter turns it into a human‑interest story. Women’s clubs, which were powerful civic actors in the 1920s, seize on it. So do some Protestant reformers and a few progressive Catholic priests.

By 1926 or 1927, you get a small “save the girls” movement. It is not feminist in the modern sense. It is maternalist. The argument is that Christian charity and American decency require families and states to protect “unfortunate girls” and their babies, not cast them out.

There were already reform currents to tap into. The Sheppard–Towner Maternity and Infancy Act of 1921 funded public health nurses to reduce maternal and infant mortality. Progressive reformers were talking about child welfare, juvenile courts, and public responsibility for children. In our counterfactual, they add a new plank: equal legal status for all children, regardless of parents’ marital status.

What changes?

First, state laws on illegitimacy begin to soften in the late 1920s rather than decades later. A few progressive states, maybe in the Midwest or Northeast, pass statutes allowing easier paternity suits and better child support enforcement. They might not yet grant full inheritance rights, but they would start to erode the idea that the child should be punished for the parents’ behavior.

Second, public funding for “mothers’ pensions” expands to include some single mothers, not just widows. In real history, mothers’ aid programs often excluded women judged “morally unfit.” In this alternate path, reformers push to separate sexual sin from child welfare. A woman who can prove the father’s identity and show she is caring for the child might qualify for small cash aid.

Third, institutions change tone. Maternity homes, many run by religious groups, were often harsh and shaming. Under reform pressure, some shift to a more “rehabilitative” model. They still push adoption in many cases, but they are less likely to coerce girls into surrendering babies. Some homes might even experiment with on‑site childcare and job training, especially in larger cities.

There would be backlash. Conservative clergy, some politicians, and plenty of parents would argue that easing the consequences of premarital sex would encourage it. Newspapers would run editorials about “rewarding immorality.” But the existence of a visible reform movement would give unwed mothers allies they mostly lacked in the real 1920s.

So what? In this scenario, the treatment of unwed mothers becomes a contested public issue a generation earlier, nudging U.S. law toward equal treatment of children and modest welfare support before the New Deal arrives.

Scenario 3: A quiet sexual revolution under the radar

The third scenario takes the “Roaring Twenties” image seriously and pushes it a bit further.

Historians know that premarital sex was already rising by the 1920s, especially among urban youth. Automobiles, dance halls, and cheap apartments gave young couples more privacy. Birth control information, though restricted by Comstock laws, was spreading through underground pamphlets and some clinics. Margaret Sanger opened the first birth control clinic in 1916 and founded what became Planned Parenthood in the 1920s.

Now imagine that, instead of doubling down on stigma, middle‑class parents quietly adapt. They do not endorse premarital sex. They do not talk about it openly. But when a daughter gets pregnant, they treat it as an unfortunate but survivable mistake, not a moral catastrophe.

In this world, the answer to the photographer’s 1925 question is often: “No, you do not throw her out. You keep it quiet and you manage it.”

What follows?

First, more routine use of family cover stories. The “grandparents raise the baby as their own” pattern becomes almost standard in some communities. Social workers and local doctors know, but they collude in the fiction. The girl finishes school, maybe marries someone else later, and the child grows up calling her “aunt.”

Second, a stronger market for birth control and abortion, earlier. If parents are less inclined to expel daughters but still desperate to avoid scandal, they have an incentive to seek out ways to prevent or end pregnancies. That means more quiet funding for birth control clinics and more protection for sympathetic doctors. Illegal abortion was already common in the 1920s. In this scenario, it becomes more normalized in private, especially for the middle class.

Third, a subtle shift in dating norms. If everyone knows, privately, that a pregnancy will not destroy a girl’s life, the terror around sex loosens. That does not mean a 1960s‑style sexual revolution. But it might mean that by the late 1930s, premarital sex among engaged or “serious” couples is even more common than it was in our timeline.

This would not show up much in public law. Churches would keep preaching chastity. Newspapers would still print moralizing advice columns. Respectability culture would survive. The change would live in the gap between what people said and what they did.

So what? In this scenario, the main effect is cultural. A less catastrophic view of unwed pregnancy quietly accelerates the long‑term trend toward more premarital sex and more private use of contraception and abortion, even while public rhetoric stays conservative.

Which alternate 1925 is most plausible, and what would it change?

Of the three, the first scenario, quiet acceptance at home without big legal change, is the most plausible.

Why? Because it demands the least from the political system. It asks parents to act differently within the same laws and churches, not to rewrite statutes or build new welfare programs. We know some families already chose this path in the real 1920s. Scaling it up requires a shift in social norms, not a revolution.

The second scenario, moral panic flipping into reform, is possible but harder. The 1920s federal government was conservative, and many states were controlled by politicians who prized public morality. Reform did happen in areas like child labor and public health, but equalizing the status of “illegitimate” children would have run into deep resistance from churches and courts. You could imagine a few progressive states moving early, but a broad national change before the New Deal is a stretch.

The third scenario, a quiet sexual revolution, partly happened anyway. Premarital sex rose, and families did use cover stories. The extra step this counterfactual adds is a more relaxed parental response, which is plausible in some urban, middle‑class circles but less so in rural or tightly religious communities. It would likely be a patchwork, not a national pattern.

So if we go with the most grounded alternate world, what changes?

First, fewer women hit absolute rock bottom. Being expelled in 1925 could mean homelessness, prostitution, or death from unsafe abortion. If more parents keep their daughters, some of those worst outcomes are avoided. That has a long tail. Children raised in slightly more stable conditions tend to have better health and schooling, which affects their adult lives.

Second, the social meaning of “illegitimacy” erodes a bit earlier. Law might lag, but if many families quietly refuse to treat these children as shameful, the word loses some of its sting. By mid‑century, when courts and legislatures start revising illegitimacy laws in our real timeline, they would be catching up to a social reality that had already softened in the 1920s and 1930s, not just the 1950s and 1960s.

Third, the history of adoption and secrecy looks different. In the real United States, the mid‑20th century saw a boom in closed adoptions, often involving intense pressure on unwed mothers to surrender babies. If more 1920s parents had normalized keeping daughters and grandchildren at home, that later adoption boom might have been smaller. More children would have grown up knowing their biological mothers, even if under a family fiction.

None of these changes turn 1920s America into a haven for single mothers. The wage gap, lack of childcare, and moralism would still be there. But the sharpest edge of punishment, the act of throwing a girl into the street for being pregnant, would be dulled.

That is why that 1925 sidewalk question still matters. It captured a moment when ordinary people were being asked to decide whether family honor was worth a daughter’s life chances. Change the answer, even a little, and you get a quieter, less visible, but very real shift in how millions of Americans came into the world.

Frequently Asked Questions

How common were children born out of wedlock in the 1920s?

Estimates vary, but historians generally place nonmarital births in the United States during the 1920s at roughly 3 to 5 percent of all births. The rate was likely higher than official numbers suggest, because some pregnancies were hidden, some babies were adopted, and some births were reclassified after quick marriages.

Did parents really throw daughters out for getting pregnant in 1925?

Yes, some did. Court records, social work reports, and memoirs from the era all describe cases where pregnant daughters were expelled or sent away. It was not universal. Other families hid the pregnancy, arranged a hurried marriage, or raised the child as their own. But the threat of being turned out was real enough to shape many women’s choices.

What legal rights did “illegitimate” children have in the early 20th century?

In most U.S. states in the early 1900s, children born outside marriage had limited rights. They often could not inherit from their fathers unless specific steps were taken, and they were treated differently in some welfare and custody laws. Over the mid‑20th century, many of these distinctions were removed, but in the 1920s the legal category of “illegitimacy” still carried real consequences.

When did U.S. society start accepting single mothers more openly?

Broad social acceptance of single motherhood is mostly a late 20th‑century story. Attitudes began to shift in the 1960s and 1970s with changing sexual norms, the women’s movement, and legal reforms that equalized the status of children regardless of parents’ marital status. In the 1920s, single mothers faced intense stigma and very limited support, though some families quietly supported daughters who had children outside marriage.