Madam C.J. Walker, “the world’s most successful female entrepreneur of her time,”, was an African American entrepreneur, business owner, philanthropist, and activist. She developed Madame C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company, a line of beauty and hair products for black woman, which was also how she made her fortune.

Born on December 23, 1867, Walker’s birth name was Sarah Breedlove. She was born in Delta, Louisiana as one of Owen and Minerva Anderson Breedlove’s six children. Sarah had an older sister and four brothers. The Breedlove family had all been enslaved to Robert W. Burney, but Sarah was the first member of their family born into freedom after the recently signed Emancipation Proclamation. Both her parents had died by her seventh birthday. At ten, she moved to work as a domestic in Vicksburg, Mississippi where she lived with her older sister Louvenia and her husband.

Sarah married Moses McWilliams in 1882 when she was fourteen. The reason she married so young was to perhaps escape her brother-in-law’s mistreatment and abuse. On June 6, 1885 , their daughter Lelia McWilliams was born. Sarah was twenty and their young daughter was two when Moses died in 1887. Though she remarried in 1894 to John Davis, she left him in 1903 and moved to Colorado two years later. In January of 1906, Sarah married for a final time to newspaper advertising salesman Charles Joseph Walker from Missouri. When she married him, she became known as Madam C.J. Walker. In 1912, they got divorced. Sarah daughter Lelia took on the name of A’Lelia Walker, using her stepfather’s surname.

Shortly after Moses dies, Sarah and her daughter moved to Saint Louis, Missouri in 1888. Three of her brothers were living in St. Louis as well. There, Sarah was able to earn barely a dollar a day by working as a laundress. Still, she was determined to make money to provide her daughter with a formal education and continued to work hard. She lived in a music where ragtime music was developing, so to make more money, Sarah began singing at the St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church. However, seeing all the educated women around her made Sarah wish she was educated.

Sarah’s brothers, who were barbers, taught her how to care for hair. Like many African American women of the time, she had begun experiencing hair loss, dandruff, and other hair problems. In 1904 at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, or World’s Fair, Sarah was a commission agent who sold products for African American hair-care company owner and entrepreneur Annie Turnbo Malone. Malone was later on Sarah’s biggest rival, but by working for her, she began to gain more knowledge on hair products.

At thirty-seven, Sarah moved with her daughter Lelia to Denver, Colorado. She was still selling products for Malone, but was also developing her own line of hair care products. The following year in 1906, she married Charles Walker and was from then on known as Madam C.J. Walker. With the new name, she began hairdressing and selling retail cosmetic cream. Walker’s husband was her partner in business and assisted her with advertizing and promotion. At first, she sold her products by going around door to door and showing other African American women in her community how to use the products to groom and style their hair.

By 1906, Walker also had her daughter Lelia in charge of operating mail orders while Walker and her husband traveled across the U.S. to expand their business. Two years later, the family moved to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Their, they opened up Lelia College to train what they called “hair culturists” and opened a beauty parlor. In 1910 in Pittsburgh, Lelia, who had by this point changed her name to A’Lelia, ran everything as Walker was establishing a new base for their company in Indianapolis. In 1913, A’Lelia also convinced her mother to open up a beauty salon and office for her company in Harlem, New York City.

The headquarters for Madame C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company was established in Indianapolis in 1910. There, Walker purchases and built a factory, hair salon, and beauty school. Eventually, they added a laboratory on for research. With her newly established staff, who were for the most part women, in the city, her business only continued to grow. She did have many rivals though, not only in the U.S., but also throughout Europe.

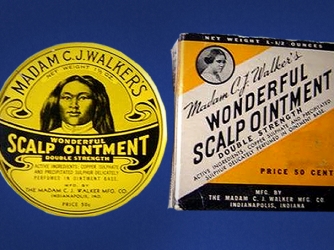

Using the “Walker System”, Walker trained the other woman in “beauty culturism”. The “Walker System” was her method of grooming that helped with hair growth and also how to properly condition the scalp with the products she sold. A shampoo and pomade were used to help the hair grow along with brushing. Walker described this method as turning hair from lackluster and brittle to much softer and more luxurious.

Walker was at the height of her career between 1911-19. During this time, she employed thousands of women as sales agents, and claimed to have trained 20,000 women by 1917. These women would go around the U.S. and the Caribbean to people’s homes, offering them her hair pomade and other products packaged nicely in little tin containers with her picture. Walker went to many great lengths to advertise her products, knowing how important it was. Primarily, she advertised them in African american newspapers and magazines. She also travelled frequently to sell products. By the 1920s, her company had expanded to Cuba, Jamaica, Haiti, Panama, and Costa Rica as well.

Not only did Walker train her employees on sales and grooming, but also showed them how to budget and build their own businesses. Walker also taught them financial independence and how to do so. She was inspired in 1917 by the National Association of Colored Women to organize her state agents into clubs locally and in states. This led to the National Beauty Culturists and Benevolent Association of Madam C.J. Walker Agents being formed. In 1917, the organization held its first annual conference in Philadelphia. Over 200 women were in attendance. It was also believed to be one of the first conferences in the country for female entrepreneurs to discuss and teach other business and commerce. Walker gave the women who sold the most products and were able to bring in the most new sales agents a prize and gave rewards to those who made large contributions to local charities.

Walker’s wealth only continued to increase, and she only continued to become more vocal with her stances. In 1912, she addressed the National Negro Business League and said: “I am a woman who came from the cotton fields of the South. From there I was promoted to the washtub. From there, I was promoted to the cook kitchen. And from there, I promoted myself into the business of manufacturing hair goods and preparations. I have built my own factory on my own ground.” She continued to make addresses at more conventions in the following years.

In Indianapolis, Walker took part in fundraising to establish a branch of the Young Men’s Christian Association, or YMCA. She pledged $1,000 to the building fund as well. She helped the Tuskegee University in Alabama by donating money to them for scholarships and also helped out many other organizations, schools, and churches.

A’Lelia moved to Harlem, New York in 1913 and Walker joined her three years later in 1916. Walker left the management of the Indianapolis headquarters to her team back in Indiana. She commissioned Vertner Tandy, the first black licensed architect in New York, to design a home for her in Irvington, New York. It cost her $250,000 to build Villa Lewaro. She intended for her new home to be a gathering place for other African American community leaders. In May of 1918, she moved into her new house and hosted an event to open her house and to honor the Assistant Secretary for Negro Affairs of the U.S. Department of War, Emmett Jay Scott.

When she relocated to New York, Walker became much more involved in politics. She began delivering lectures at conventions that powerful black institutions were sponsoring. She was one of the Circle For Negro War Relief’s leaders during the Great War. Walker also advocated for there to be training camps for black soldiers in the army established and joined the executive committee of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in New York. The organization organized the Silent Protest Parade in New York City, a silent demonstration of over 8,000 African Americans protesting a riot that had killed thirty-nine African Americans in St. Louis.

The National Association of colored Women’s Clubs honored her because she made the largest donation of any individual to preserve Frederick Douglass’s house in Anacostia in 1918. Shortly before she died in 1919, Walker pledged $5,000 (which is close to $65,000 today) to the anti-lynching found for the NAACP. This was the largest gift the NAACP had ever received from an individual. Before her death, she gave nearly $100,000 to various orphanages institutions, and individuals as well. Two-thirds of her wealth was donated to charity in her will.

At the time of her death, Walker was considered to be the wealthiest African American woman in the country and also the first self-made millionaire. However, at the time her estate was worth $600,000, so not a million. Today, that would be worth about $8 million. Sarah Walker died of kidney failure and complications due to hypertension when she was fifty-one on May 25, 1919. Her remains were interred in The Bronx, New York City at the Woodlawn Cemetery.