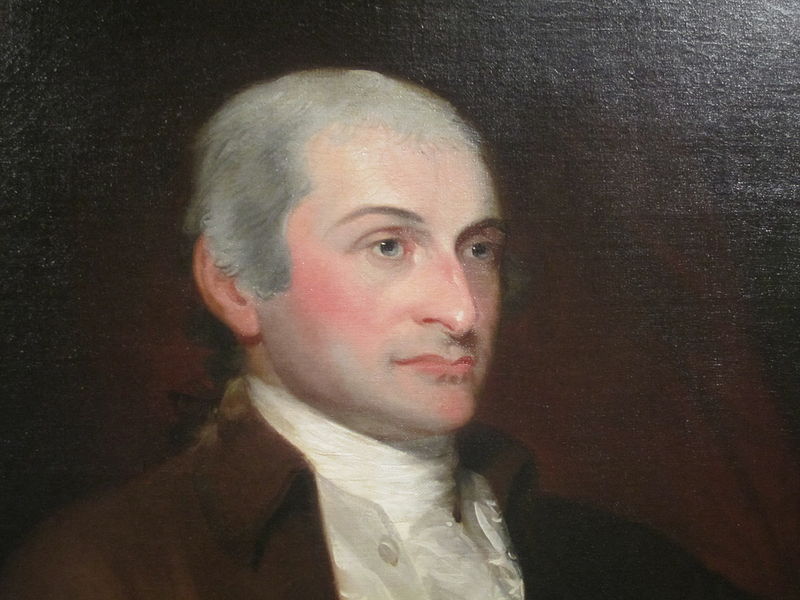

Founding Father John Jay was a patriot and diplomat along with one of the signers of the Treaty of Paris. Along with that, he was the second Governor of New York, 1st Chief Justice of the United States, President of the Continental Congress, and the U.S. Secretary of Foreign Affairs. For a few months, he acted as the U.S. Secretary of State before Thomas Jefferson and was also a diplomat in Spain. Jay was a leading slavery opponent and made many attempts to put an end to slavery in New York, and eventually succeeded.

On December 23, 1745, John Jay was born in New York City to Peter Jay and Mary Van Cortlandt. His father came from a wealthy merchant family and his mother’s father was a politician in New York. Three months after Jay was born, they moved to Rye, New York so Peter could retire after two of his children were blinded by an epidemic of smallpox.

Growing up in Rye, Jay’s mother educated him until he was sent to New Rochelle when he was eight. There, he studied under Pierre Stoupe, an Anglican priest. Three years later he returned home to continue his homeschooling with his mother.

At fifteen, Jay started at King’s College in New York City, which was later renamed Columbia College at the time of the American Revolution. Jay met and befriended many future influential people. Robert Livingston, who was the son of a prominent aristocrat and Supreme Court Justice, was one of his closest friends. Like his father, Jay became a Whig. Four years later in 1764, he graduated and went on to work for Benjamin Kissam as a law clerk.

Jay was admitted to the New York Bar in 1768. He used money from the government to establish his own legal practice. For three years, Jay worked there until in 1771 he created a law office. Up until 1774, he was a member of the New York Committee of Correspondence, then becoming its secretary.

[ebaylistings]

A member of the conservative faction, he believed in protecting property rights along with preserving the law and feared “mob rule”. Though he believed it was wrong for the British to tax Americans without proper representation, in the First Continental Congress, which he was a delegate of, he was on the side of the delegates hoping for conciliation with Parliament. Jay continued to work hard as a supporter of the revolution and suppressed the Loyalists when the war broke out. He had started off as a moderate patriot, but soon become a very ardent and passionate one when he realized that there was no way they could reconcile with Britain.

On April 28, 1774, John Jay married the eldest daughter of the New Jersey Governor William Livingston, Sarah van Brugh Livingston. Sarah was nearly ten years his junior at seventeen while he was twenty-eight. They had six children (Peter Augustus, Susan, Maria, Ann, William, and Louisa). When Jay went to Spain as a diplomat, she joined him. Their children also accompanied them to Paris where they lived with Benjamin Franklin for some time. After both his parents died, Jay was especially stressed out after having to care for his two bling siblings, his brother with a mental disability, and his brother dealing with financial problems.

Like many wealthy New Yorkers of his time, Jay owned slaves. Though after 1777, he began working to abolish slavery. He even drafted a law to abolish slavery, but it did not pass, and neither did a similar one in 1785. Nearly every member of the New york legislature in 1785 agreed to emancipate slaves in New York, but they argued on what freedoms should be given to former slaves. After the war, many slaveholders in New York freed their slaves, but that did not mean that all were free. In 1785, he founded the New York Manumission Society with the purpose of boycotting newspapers and merchants that were involved in the slave trade. Along with that, they also provided legal help to free blacks that were either claimed to be slaves or kidnapped.

As Governor of New York, Jay signed a law of gradual emancipation that the Society had helped enacting in 1799. By July 4, 1827, all slaves in new York were emancipated.

Shortly before the American Revolution broke out, Jay was elected to serve on both the First and Second Continental Congress. Originally, Jay favored rapprochement and also assisted in writing the Olive Branch Petition, which was a petition asking the British to reconcile with the colonies. However, it soon became evident that war would break out and there would not be reconciliation, so Jay began supporting both the revolution and the Declaration of Independence. Originally a moderate supporter, by the time the war began, he was staunchly and ardently supporting the war.

Jay returned home to New York when the Continental Congress closed and served on the Committee of Sixty. When he was elected to the third New York Provincial Congress, he drafted the Constitution of New York in 1777. As a Congressman, he was unable to vote on or sign the Declaration of Independence. On May 8, 1777, he was elected Chief Justice of the New York Supreme Court of Judicature.

Not even a week after becoming a delegate to the Continental Congress, he was elected President of it. Eight states voted for him while four voted for Henry Laurens. So from December 10, 1778-September 28, 1779, he served as President of the Continental Congress. Jay did not have much power in this role, and it was for the most part ceremonial.

Jay’s term as President of the Continental Congress came to an end when he was appointed Minister to Spain on September 27, 1779. There, he was looking for financial aid and commercial treaties along with the Spanish to recognize the ongoing war. The Spanish royal court feared that recognizing American Independence would start a revolution in their own colonies, so they refused to officially receives him as Minister of the United States. While unable to meet with them, Jay was able to convince them to give the US government a loan of $170,000 and departed the country after two and a half years on May 20, 1782.

From Spain, Jay travelled to Paris, arriving on June 23, 1782. There, they were beginning negotiations to end the American Revolution with a treaty. Out of the group, Benjamin Franklin was the most experienced in diplomacy, which is why Jay wanted to stay near him so he could learn from him. First, the U.S. agreed to meet with the British and then with the French afterwards. Over a year later, the war came to an official end when the Treaty of Paris was signed on September 3, 1783 after having been drafted the previous November. It became effective on May 12, 1784.

Upon his return to the U.S., Jay served as the Secretary of Foreign Affairs until 1789. The September of 1789, Congress passed a law that gave the department more domestic responsibilities and the department’s name was also changed to the Department of State. Up until March 22, 1790, Jay was the acting Secretary of State. During this time, he worked to establish a strong foreign policy for the U.S. that would be long lasting. He also hoped to gain recognition from the European powers, who unlike the U.S., were already well established and much more powerful. On top of all that, Jay worked on establishing a stable currency for the country so they could pay off their heavy ward debts. Jay was able to achieve many other things during this time, including securing fishing rights in Newfoundland, establishing a robust maritime trade route for goods from American, solve regional difficulties within the colonies, and much more.

Jay joined Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, two other founding fathers and prominent politicians, in advocating for a much stronger government instead of the Articles of Confederation in 1788. While not in attendance of the Constitutional Convention, Jay ended up joining with the two in working aggressively to promote the new Constitution. So together, they penned the Federalist Papers under the name of “Publius”. Overall, they wrote eighty-five articles, with Jay only writing five, Madison writing twenty-nine, and Hamilton fifty-one.

When offered the position of Secretary of State by the new president, George Washington, in September of 1789, Jay declined. In response, Washington instead offered him the title of Chief Justice of the United States, which Jay then accepted. The nomination was then made official the same day the position was signed into law by the Judiciary Act of 1789 on September 24, 1789. Two days later, the senate unanimously confirmed him and that day, Washington signed and sealed the commission. The following month on October 19th, Jay was sworn in.

For the first three years, the court mainly worked on establishing rules and procedure, reading commissions and attorneys’ admissions to the bar, and duties of the Justices. Due to a light workload, Jay often was involved with Washington and his administration.

During Jay’s time as Chief Justice, only four cases were heard. The first, West v. Barnes, was in 1791, almost two years after the court was created. In 1792, Hayburn’s Case was heard then Chisholm v. Georgia the following year, and finally, Georgia v. Brailsford.

As a Federalist, Jay ran for governor of New York, but was defeated by his Democratic-Republican opponent, George Clinton. Though Jay did receive more votes, a few of the counties were technically disqualified, and therefore Clinton barely beat him.

In 1794, the U.S. and Britain were on the verge of yet another war because of exports from Britain dominating the market in America. However, the British were blocking American exports. On top of that, Britain had agreed to surrender forts in the north in the Treaty of Paris, but at that point they were still occupying them. More conflict was created by the British impressment of American sailors and taking their ships and supplies. James Madison proposed a trade war, but this was rejected by Washington, who sent Jay to Great Britain as a special envoy to work on negotiating a new treaty. While he was gone, Jay kept his position as Chief Justice. Alexander hamilton wrote out instructions for Jay under Washington’s request for what to do when negotiating. By March of 1795, Jay returned and brought the result, the Jay Treaty, to Philadelphia. Hamilton wanted to keep up good relations and told the British that they wanted to remain neutral and would not join the Swedish or Danish governments. This made Jay loose most of the leverage he had.

Though the treaty got rid of British ports in the northwest and the U.S. was given “most favored nation” status along with the U.S. agreeing to restrict commercial access to the British West indies, there were still many grievances. The Democratic-Republicans denounced the neutral shipping rights and impressment. As Chief justice, Jay decided not to take part in any debates regarding the treaty. The British did continue to impress American ships, which was part of the reason of the War of 1812. Washington believed in the treaty and the Federalists, Hamilton included, were not opposed to it. In the end, the treaty was ratified with a 20-10 vote by the Senate, which was the exact amount to meet the requirement of a two-thirds vote. The Democratic-Republicans believed this to be a betrayal of American interests. Many also wrote graffiti with rude messages to John Hay.

In May 1795, John Jay succeeded George Clinton as Governor of New York. On June 29, 1795, he resigned from the Supreme Court. Jay spent six years as governor, leaving office in 1801. In 1796, Jay even ran in the presidential election, though he only won five electoral votes, and one when he ran again in 1800.

Jay declined the nomination for governor in 1801 and a nomination to return to his post as Chief Justice, but he declined both. He decided to retire from politics to lead a private life of a farmer in Westchester County, New York. Not long after, his wife died. For the most part, Jay stayed out of politics while he farmed and was able to maintain good health. However, there was one exception when it came to politics when he condemned Missouri’s bid as a slave state to be admitted to the union in 1819 in a letter. In 1814, thirteen years after retiring, Jay and his son, Peter Augustus Jay, were both elected to serve on the American Antiquarian Society.

On May 14, 1829, Jay most likely had a stroke when he was struck with palsy that night. For three days, he lie awaiting his death in Bedford, New York before passing away on the 17th. John Jay was buried in his childhood hometown of Rye.