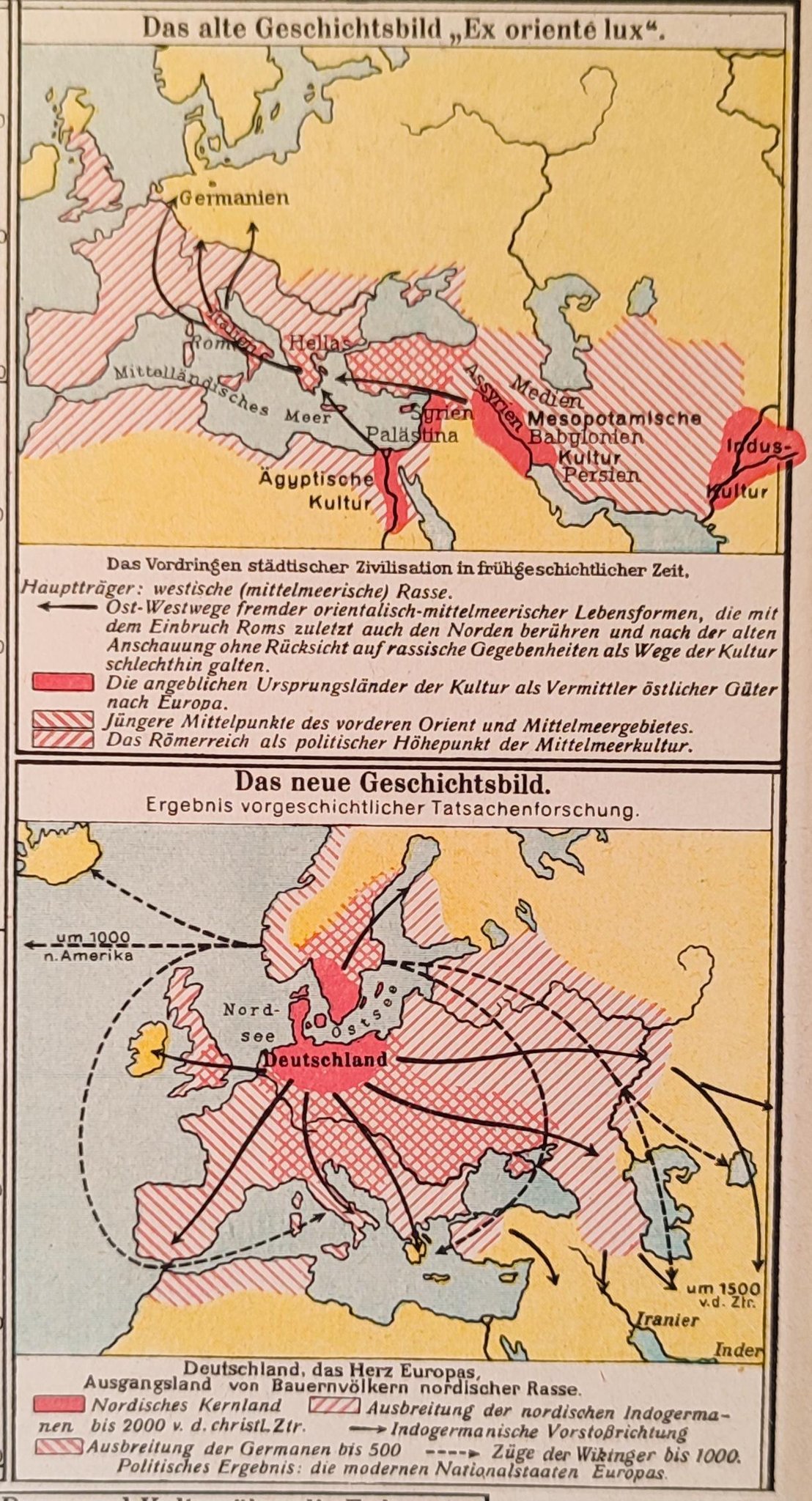

They look similar because both try to answer the same grand question on a flat sheet of paper: where did civilization begin, and how did it spread? One is a 1942 German propaganda map claiming culture radiated out of Germany. The other is the modern historical picture, built from archaeology, linguistics, and genetics. On the wall, they can look oddly alike: arrows, shaded zones, sweeping claims about human progress. Underneath, they could not be more different.

The Nazi map, printed in the middle of World War II, shows Europe as a kind of cultural solar system with Germany at the blazing center. Arrows shoot outward. Civilizations are rebranded as Germanic exports. It is not a map of the past so much as a political fantasy of the present.

Modern historians also map the spread of agriculture, languages, and states. They draw arrows from the Fertile Crescent, the Nile, the Indus, the Yellow River. They talk about Indo-European migrations and trade routes, not racial destiny. By the end of this comparison, the shared visual grammar of these maps will be clear, and so will the gulf between propaganda and evidence.

Origins: Why did Nazis draw a “civilization from Germany” map?

The 1942 German propaganda map did not appear out of nowhere. It grew out of a longer obsession in German nationalist and völkisch circles with proving that “true” civilization was Germanic at its core.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a cluster of racial theorists and amateur prehistorians argued that Indo-European, or “Aryan,” culture began in northern Europe. Writers like Houston Stewart Chamberlain and later Alfred Rosenberg recast history as a racial saga with Germans as the heroic originators. By the time the Nazis took power in 1933, this was ready-made ideology.

The Nazi state then built institutions to give this myth a scholarly sheen. The most notorious was the Ahnenerbe, founded in 1935 under Heinrich Himmler. It funded expeditions and research that were supposed to prove ancient German superiority, from excavations of Germanic sites to quixotic trips to Tibet.

Maps were perfect tools for this project. A map can make a wild claim look orderly and scientific. If you shade Germany in a bold color and draw thick arrows outward, you visually “prove” that culture spread from there, even if the evidence is thin or fabricated.

By 1942, Germany was deep into a world war that it had started. The regime needed to justify conquest in Poland, France, the Balkans, and the Soviet Union. A map showing civilization emerging from Germany did ideological work: it implied that German domination was a kind of homecoming. Germans were not occupiers, they were reclaiming the stage they had built.

Modern historical maps of civilization have a very different origin story. They grow out of 19th and 20th century archaeology in Mesopotamia and Egypt, the deciphering of cuneiform and hieroglyphs, radiocarbon dating from the 1950s onward, and later, genetic and linguistic research. When historians say that early urban civilization emerged in places like Sumer or along the Nile, they are summarizing tens of thousands of excavated sites and texts, not a racial theory.

So what? The Nazi map was born from ideology looking for evidence, while modern maps grow from evidence that historians try to explain. That reversal at the origin point shapes everything that follows.

Methods: How did propaganda cartographers twist the past?

Propaganda maps and scholarly maps can use the same symbols but for opposite purposes. The 1942 German map used a few basic tricks.

First, it redefined “civilization” in racial and cultural terms that fit Nazi doctrine. Civilization, in this view, meant whatever could be plausibly labeled “Germanic” or “Aryan.” Celtic, Roman, and Slavic contributions were minimized or absorbed. Greek culture might be recast as an offshoot of Nordic migrants. Roman achievements became the work of Aryan elites ruling over lesser peoples.

Second, it cherry-picked and distorted archaeological and linguistic evidence. The Indo-European language family was real. So were prehistoric cultures in central and northern Europe like the Corded Ware and Bell Beaker cultures. Nazi-influenced scholars simply declared these to be “Germanic” in a modern sense, then drew arrows from those zones to later civilizations. Gaps of thousands of years and vast cultural differences were smoothed over by a few lines of ink.

Third, the map collapsed time. Prehistoric migrations, classical empires, medieval kingdoms, and modern nation-states were all folded into a single story of German expansion and cultural radiation. It suggested a straight line from Stone Age farmers in central Europe to the Third Reich.

Modern historical mapping works almost in reverse. Historians define “civilization” in institutional and material terms: cities, writing systems, complex states, specialized labor, long-distance trade. When they map the “cradles of civilization,” they point to regions like:

• Southern Mesopotamia (Sumer), with urban sites like Uruk around 3500–3000 BCE.

• The Nile Valley, with Egyptian state formation by around 3100 BCE.

• The Indus Valley, with cities like Mohenjo-daro and Harappa by about 2600 BCE.

• The Yellow River basin in China, with early states by the late 2nd millennium BCE.

They use radiocarbon dates, stratigraphy, inscriptions, and settlement patterns to place these developments in time and space. When they draw arrows, they usually mean specific processes: the spread of agriculture from the Fertile Crescent into Europe over millennia, or the diffusion of alphabetic writing from the Levant to Greece.

Modern scholars also separate language, genes, and culture. Indo-European languages may have spread from the Pontic-Caspian steppe around 3000 BCE, but that does not mean a single “race” carried all civilization with it, or that modern Germans are the direct heirs of every Indo-European speaker.

So what? Nazi cartographers used maps to erase complexity and compress time into a racial myth, while modern methods insist on separating different kinds of evidence and keeping timelines honest, which makes propaganda-style claims much harder to sustain.

Outcomes: What did each mapping project actually do?

A propaganda map is not just wrong on paper. It has real-world consequences. The 1942 German map fed directly into wartime policy and violence.

If civilization supposedly radiated from Germany, then German rule in Europe could be sold as natural and beneficial. Nazi ideologues argued that Slavic peoples in Eastern Europe were “culture bearers” at best, not originators. The map visually supported the idea that Germans had a historic right to colonize the East, seize land, and reorder populations.

This fed into Generalplan Ost, the secret Nazi blueprint for ethnic cleansing and colonization in Eastern Europe. While the plan was not literally based on one poster map, they shared the same mental world: a Germany that had always been the engine of European progress, now taking what was “owed.”

Inside Germany, such maps helped educate children and the public into a distorted past. Classrooms used wall maps to teach racial hierarchies and historical destiny. When you grow up seeing your country at the center of every story, conquest can feel like restoration rather than aggression.

Modern historical maps of civilization have very different outcomes. They have their own problems, especially in earlier 20th century versions that overemphasized Europe and the Near East while marginalizing Africa, the Americas, and Oceania. But their main effect has been to widen the story of where complex societies emerged.

Maps of early states now include urban centers in West Africa like Jenné-jeno, complex societies in the Andes and Mesoamerica, and early rice-growing cultures in East and Southeast Asia. The “cradles of civilization” are no longer drawn as a single line that inevitably leads to modern Europe.

There is a simple, snippet-ready contrast here: A Nazi propaganda map of civilization was designed to justify German racial supremacy and conquest. Modern historical maps of civilization are attempts to summarize where and when complex societies first appeared based on archaeological evidence.

So what? The Nazi map helped normalize a violent imperial project, while modern mapping of early civilizations, for all its revisions and debates, has tended to break the monopoly of any one region on the story of human complexity.

Legacy: How did the Nazi map and modern history shape memory?

The Third Reich fell in 1945, but its maps did not vanish. Copies sat in archives, attics, and old school buildings. Today, when one of these 1942 maps surfaces online, it often shocks viewers with its brazenness: arrows from Germany to Greece, Rome, maybe even India, all implying a single Germanic civilizing mission.

In postwar Germany, such materials became evidence in denazification and war crimes trials. They showed how deeply racial ideology had been woven into education and public messaging. Later, historians of propaganda used these maps to study how visual tools can naturalize extreme ideas.

The legacy is double-edged. On one hand, the map is a historical artifact that helps us understand how ordinary Germans were taught to see the world. On the other, it remains a resource for neo-Nazi and far-right groups that still try to recycle old racial myths about “Aryan” origins and civilizational superiority.

Modern historical maps of civilization have their own legacy, and it is not spotless. Mid-20th century textbooks often put Mesopotamia and Egypt on page one, then treated Greece and Rome as the inevitable heirs, with everyone else in the background. This fed a Eurocentric story in which civilization marched west and north until it reached its supposed peak in Western Europe and North America.

From the late 20th century onward, that picture has been heavily revised. Archaeology in China, India, Africa, and the Americas has pushed back dates and expanded the map of early complex societies. Genetic studies have complicated simple migration stories. Historians now talk about multiple centers of innovation, connected by trade, war, and borrowing.

There is another snippet-ready contrast here: Nazi maps of civilization tried to compress the past into a single racial origin story. Modern scholarship has moved toward a plural origin model, in which several regions independently developed complex societies that later interacted.

So what? The Nazi map’s legacy is a warning about how easily maps can be weaponized, while the shifting legacy of scholarly maps shows that even well-intentioned narratives about “where civilization began” need constant revision to avoid sliding back into hierarchy and myth.

Why do propaganda maps and real history maps still look alike?

Put the 1942 German propaganda map next to a modern map of Indo-European language spread or Neolithic farming, and you can see why people get confused. Both have arrows across Europe. Both shade regions and suggest movement from one core area to others.

They look similar because maps have a limited visual vocabulary for showing change over time. Arrows, gradients, and shaded zones are the standard tools. A dishonest mapmaker can borrow the style of scientific maps to sell a political story.

But if you look closely, the differences jump out. Propaganda maps usually have:

• A single, clear hero region at the center.

• Very long arrows that skip centuries and ignore intermediate cultures.

• Vague or absent dates, or timelines that compress thousands of years into one movement.

• Racial or national labels projected backward onto prehistoric groups.

Evidence-based historical maps tend to show:

• Multiple centers of development.

• Shorter, more specific arrows tied to particular periods or processes (like the spread of farming around 6000–4000 BCE).

• Dates or time ranges attached to movements.

• Cultural or linguistic labels that are tentative and often debated, not treated as eternal identities.

So what? The visual grammar can be similar, but once you know what to look for, you can tell when a map is summarizing evidence and when it is trying to drag the past into someone’s political present.

What the 1942 map gets wrong about “where civilization came from”

Strip away the arrows and slogans, and the core claim of the 1942 map is simple: civilization emerged from Germany or the broader Germanic world. That is not supported by any serious body of evidence.

The earliest known urban civilizations with writing, monumental architecture, and complex states appear in Southwest Asia and Northeast Africa. Sumerian city-states like Uruk, early dynastic Egypt, and later Akkadian and Babylonian polities are centuries or millennia older than anything comparable in central or northern Europe.

Early agriculture in Europe does not originate in Germany. It spreads from the Fertile Crescent through Anatolia into the Balkans and then gradually north and west, reaching central Europe well after it appears in the Near East. Archaeologists can track this through plant remains, animal bones, and characteristic pottery styles.

Germanic-speaking peoples, as far as we can tell, emerge as a distinct group in the first millennium BCE and become visible in Roman sources in the last centuries BCE and first centuries CE. They are important actors in late antiquity and the early Middle Ages, but they are not the origin point of civilization itself.

Modern historians do recognize that Indo-European languages, which include Germanic, Greek, Latin, Sanskrit, and many others, spread widely from a probable homeland on the Pontic-Caspian steppe. But that linguistic spread is not the same thing as the birth of civilization, and it does not map neatly onto modern nations or races.

So what? The 1942 map takes a real human desire to know “where it all began” and answers it with a flattering myth for one nation. The modern evidence-based answer is messier, less flattering to any single group, and far more interesting.

In the end, the comparison is straightforward. The Nazi “civilization from Germany” map is a wartime poster for racial destiny, dressed up as history. Modern maps of early civilizations are imperfect, evolving attempts to summarize a global, multi-origin story. They may share arrows and shaded zones, but one is trying to close the past around a single people, while the other keeps finding more starting points.

Frequently Asked Questions

What did the 1942 German propaganda map claim about civilization?

The 1942 Nazi propaganda map claimed that civilization emerged from Germany or the broader Germanic world and then spread outward. It used arrows and shading to suggest that major cultures, from classical to modern, were essentially products of ancient Germanic or “Aryan” expansion, which fit Nazi racial ideology and wartime ambitions.

Where do historians say civilization actually began?

Most historians define early civilizations as complex urban societies with writing, states, and specialized labor. The earliest known examples appear in several regions: Sumer in southern Mesopotamia, early dynastic Egypt along the Nile, the Indus Valley cities, and early Chinese states along the Yellow River. These developed long before comparable complexity in central or northern Europe.

How can I tell if a historical map is propaganda?

Propaganda maps often put one country or group at the center, use very long arrows that skip centuries, avoid clear dates, and project modern national or racial labels backward in time. Evidence-based maps usually show multiple centers of development, give time ranges, and separate language, culture, and genetics instead of treating them as a single, eternal identity.

Did Indo-European or “Aryan” peoples create all civilization?

No. Indo-European is a language family, not a single race or civilization. Indo-European languages likely spread from the Pontic-Caspian steppe several thousand years ago, but early urban civilizations also emerged in regions where non–Indo-European languages were spoken. Civilization arose independently in several places, and later cultures borrowed and mixed ideas across language and ethnic lines.