They look similar because, at first glance, both Marie Antoinette’s final note and her public image are about emotion and drama. One is a tiny scrap of paper written at 4.30 a.m. before the guillotine. The other is a giant caricature of a frivolous, heartless queen. Both seem to tell you who she was. Only one is actually her voice.

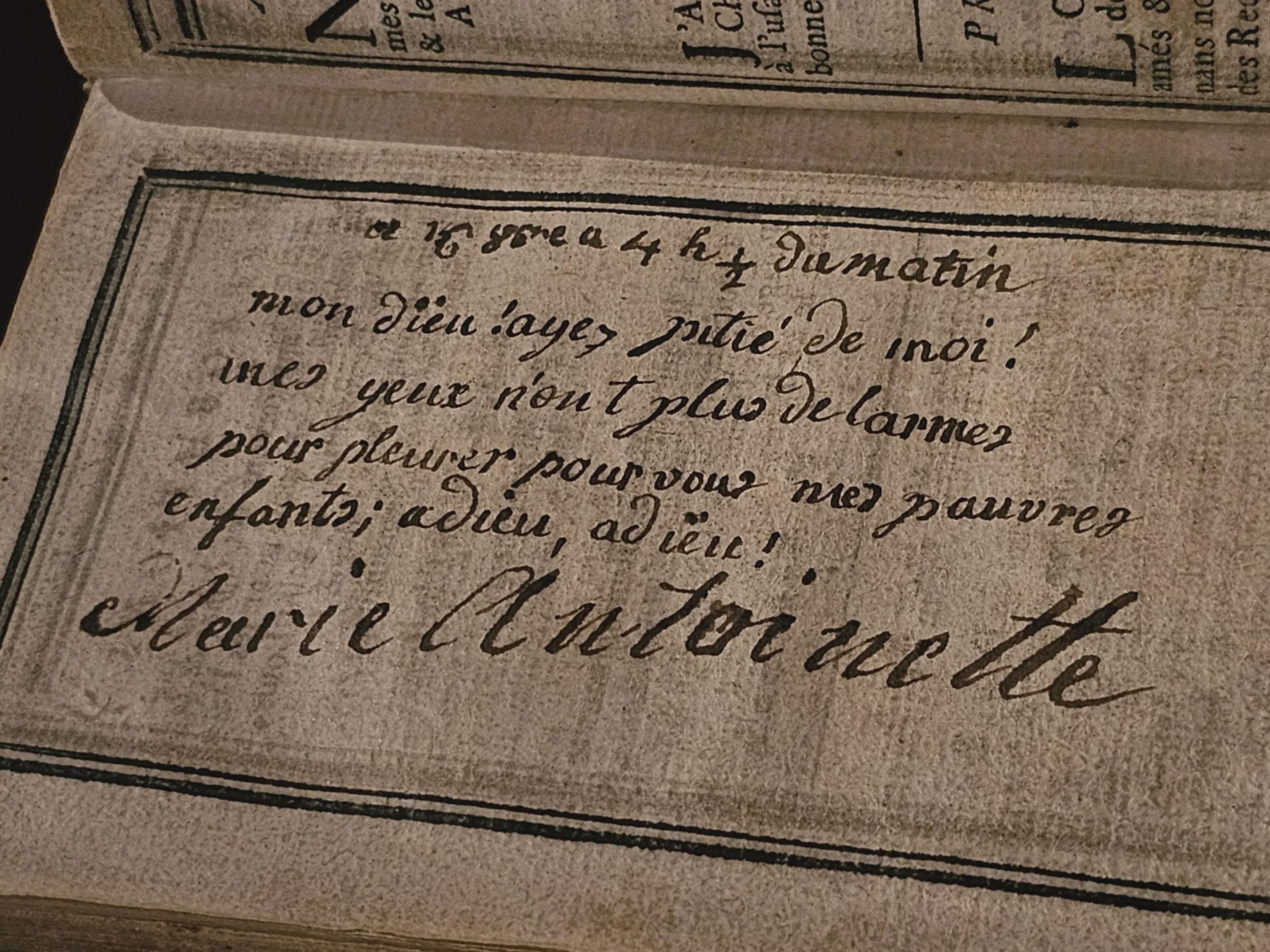

The note on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum is short and raw: “My lord, have pity on me! My eyes have no more tears to cry for you my poor children; farewell, farewell!” It was written on 16 October 1793, hours before she was executed in Paris. For many visitors, it clashes violently with the cartoon villain they think they know.

Marie Antoinette’s final letter is a primary source, written in her own hand before her death. The popular image of Marie Antoinette is a political construction, built from pamphlets, propaganda and later retellings. Comparing the two shows how revolutions make, and unmake, people’s reputations.

Origins: a queen on paper vs a queen on the scaffold

The famous last note has a clear origin. In the early hours of 16 October 1793, Marie Antoinette was in her cell in the Conciergerie prison, under sentence of death. She had been tried by the Revolutionary Tribunal the day before and condemned as an enemy of the people.

She wrote a longer final letter that night to her sister-in-law, Madame Élisabeth, often called her “spiritual will.” The short line quoted in the Reddit post is part of that final message. In French, she begged for pity, spoke of her children, and said farewell. The letter never reached Élisabeth. It was intercepted by revolutionary authorities and preserved in the archives.

So the note has a traceable chain: written by Marie Antoinette, seized by the state, later catalogued, and now displayed in exhibitions like the one at the V&A. Historians have handwriting, context, and parallel documents to work with. It is, as far as sources go, solid.

The myth of Marie Antoinette has a messier birth. She arrived in France in 1770 as a teenage Austrian archduchess, married to the future Louis XVI. At first she was a diplomatic symbol, a Habsburg princess meant to seal peace between France and Austria.

Very quickly, she became something else: a blank canvas for French anxieties. Libellistes, the underground pamphleteers of the late 18th century, turned her into “l’Autrichienne,” the Austrian woman, a pun that also sounded like “other bitch” in French slang. They accused her of sexual depravity, political treason, and financial waste long before the revolution.

The most famous line attached to her, “Let them eat cake,” is a good example of how this myth was stitched together. There is no reliable evidence she ever said it. A similar phrase appears in Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Confessions, written before she was even queen, and he attributes it to an unnamed “great princess.” The line stuck to her later because it fit the story people wanted to tell about a callous aristocracy.

So the note comes from a sleepless woman in a cell, while the legend comes from pamphlets, gossip, and political need. That difference in origin matters because it tells us which Marie Antoinette we are looking at: the person, or the symbol that others built.

Methods: handwriting vs propaganda machines

Marie Antoinette’s final note is a study in limited means. She had a bit of paper, a writing instrument, and a few hours before dawn. She wrote in the formal, devout style of an 18th-century Catholic princess, but the content is stripped down: fear, faith, and her children.

In that last letter, she affirms her innocence as she sees it, forgives her enemies, and commends her soul to God. The line quoted in the Reddit post is one of the few moments where the mask slips and the mother speaks more plainly: no more tears left, farewell to her children. It is not political. It is private grief that happened to survive.

The method here is intimate. One hand, one page, meant for one reader. She was not writing for history or for the crowd at the scaffold. She thought she was writing to a family member who shared her faith and her world.

The myth used very different tools. Anti-Marie Antoinette propaganda was industrial for its time. Pamphlets, satirical prints, pornographic cartoons, coffeehouse gossip, and salon chatter all worked together.

Engravers drew her as a harlot, a foreign agent, a spendthrift. Writers accused her of ruining the finances of France with her dresses and parties, even though royal debt had deeper structural causes. When the diamond necklace scandal erupted in the mid-1780s, she had not ordered the necklace and had refused it, but the story that she was behind the fraud was too good to let go. She was blamed anyway.

Revolutionary leaders used her as a teaching aid. If you wanted to explain why the old regime deserved to fall, you did not print a chart of tax structures. You printed Marie Antoinette as a monster of luxury and indifference. A simple, repeatable villain made the revolution’s story easier to tell.

So the note is a single, unamplified voice, while the myth is the product of a coordinated culture of attack. That contrast in method matters because it explains why the legend is louder than the letter.

Outcomes: what the note did vs what the myth did

In October 1793, Marie Antoinette’s final note did almost nothing. It did not save her. It did not reach her intended recipient. It did not change the verdict of the Revolutionary Tribunal.

She was taken from the Conciergerie to the guillotine in a plain cart, not the covered carriage her husband had used. Witnesses described her as pale and composed. At around midday, the blade fell. The letter sat in a file, unread by the woman she addressed as “my sister.”

For years, the note had no public outcome at all. It was a private relic in state hands. Only later, as royalists and then historians combed through the archives, did it start to be published and quoted. Its immediate impact in 1793 was zero. It mattered only to the woman who wrote it and the God she believed was listening.

The myth, by contrast, had very real outcomes in her lifetime. The image of Marie Antoinette as a foreign, wasteful, sexually corrupt queen helped erode respect for the monarchy long before 1789. When bread prices rose and people starved, the story that the queen did not care made anger easier to focus.

During her trial, prosecutors leaned heavily on this constructed image. They accused her of conspiring with foreign powers, of corrupting her son, of draining the treasury. The charges were a mix of real political concerns and wild exaggerations fed by years of pamphlets. The jury needed only a few hours to condemn her.

The legend also shaped how the revolution treated her body. Louis XVI had been guillotined in January 1793 as a failed king. Marie Antoinette was executed as “Widow Capet,” a hated symbol of the old regime’s decadence. Her corpse was thrown into an unmarked grave in the Madeleine cemetery. No ceremony. No marker. Just quicklime and anonymity.

So in 1793, the note was a whisper that went nowhere, while the myth helped send her to the scaffold and into an unmarked pit. That imbalance of outcome shows how much more power public stories have than private words in a time of revolution.

Legacy: how the last note reshaped her image

Over the 19th century, the balance began to shift. The monarchy returned in various forms. Royalist writers went hunting for martyrs. They found Marie Antoinette in the archives.

Her final letter, including the line about her children and her tears, became part of a new narrative. Instead of the whore of pamphlets, she became a suffering queen and mother, a victim of Jacobin cruelty. Painters showed her in prison, pale and noble. Biographers quoted her letters to prove her piety and courage.

The same note that had no effect in 1793 now helped rehabilitate her. It was printed in collections of last words and in histories of the revolution. It gave later readers a direct emotional line to the woman behind the myth.

The myth did not disappear. “Let them eat cake” survived and spread, especially in the English-speaking world. It was too useful as a shorthand for elite indifference. Schoolbooks, films, and pop culture kept the caricature alive. Sofia Coppola’s 2006 film, for instance, played with the image of the fashion-obsessed teenager in a world of pastel excess.

Yet historians kept returning to the documents. The more her real letters were published, the more complicated she became. She was not innocent in a political sense. She did plot to save the monarchy. She did misjudge the mood of France. She did spend heavily on fashion and gambling in her early years. But she was also not the cartoon monster of the pamphlets.

Today, the final note and the myth coexist. Museum visitors read her last words and feel sympathy. Then they remember the cake line and the diamonds and feel suspicion. The tension between those reactions is the space where modern biographies now live.

So the note’s legacy has been to humanize her, while the myth’s legacy has been to keep her as a symbol of class arrogance. That clash matters because it shows how later generations negotiate between empathy and anger when they remember the past.

Why they look similar, and why that’s misleading

On the surface, the final note and the public myth both look like stories about emotion. One is a queen sobbing for her children. The other is a queen shrugging at starving peasants. Both are simple, memorable images.

That similarity is why they stick. Humans like clear narratives. A heartless aristocrat fits the French Revolution as a morality play. A tragic mother on the way to the scaffold fits the counter-story of royal martyrdom. Each compresses a messy life into one feeling.

But the sources behind those feelings are not equal. The final note is a primary document with a known author, date, and context. The cake quote is hearsay, misattributed, and almost certainly false. The pornographic pamphlets are sources too, but they tell us more about the fears and fantasies of their writers than about Marie Antoinette herself.

When people stand in front of the note at the V&A, they are often startled by the handwriting. It is small, careful, and very human. It does not look like a symbol. It looks like a person trying to keep control as her world collapses.

That is the real comparison: a single fragile object versus a giant, noisy legend. The note reminds us that even the most hated figures in history had private moments that do not fit the slogans attached to them.

So what? Because learning to separate a person’s own words from the stories told about them is not just a Marie Antoinette problem. It is a basic skill for reading any era, including our own.

Why it still matters to read the note against the myth

Marie Antoinette’s last note is not a magic key that proves she was secretly good. It is a fragment that shows one side of her at one moment. The myth of Marie Antoinette is not pure fiction either. It grew out of real inequality, real anger, and real political mistakes.

What the comparison gives us is a way to see how reputations are made. A young woman sent abroad for a dynastic marriage became, through the machinery of gossip and revolution, a symbol of everything wrong with a system. Then, through the machinery of restoration and nostalgia, she became a martyr.

The scrap of paper at 4.30 a.m. on 16 October 1793 sits in the middle of that process. It is one of the few moments where we can hear Marie Antoinette without a pamphleteer or a propagandist in the way. She is not talking about cake or diamonds. She is talking about her children and her fear.

That does not erase what the revolutionaries were angry about. It does complicate the story they told to justify killing her. And it complicates the story royalists later told to sanctify her.

So what? Because when you stand in front of Marie Antoinette’s final note, you are not just looking at a relic of a dead queen. You are looking at a rare moment where a human voice cuts through two centuries of noise. The comparison with her myth shows how easily that voice can be drowned out, and how much work it takes to hear it again.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did Marie Antoinette really say “Let them eat cake”?

There is no reliable evidence that Marie Antoinette ever said “Let them eat cake.” A similar line appears in Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s writings, attributed to an unnamed “great princess” before she was even queen. The quote stuck to her later because it fit revolutionary propaganda about a heartless aristocracy.

What did Marie Antoinette write in her final letter?

In her final letter, written around 4.30 a.m. on 16 October 1793, Marie Antoinette addressed her sister-in-law Madame Élisabeth. She affirmed her faith, forgave her enemies, and expressed grief for her children. The line often quoted is: “My lord, have pity on me! My eyes have no more tears to cry for you my poor children; farewell, farewell!” The letter never reached Élisabeth and was intercepted by revolutionary authorities.

Why was Marie Antoinette so hated during the French Revolution?

Marie Antoinette was hated for several overlapping reasons. She was foreign, an Austrian in a country suspicious of Austria. She was associated with court luxury at a time of economic hardship. Underground pamphlets accused her of sexual immorality and political treason. Revolutionary leaders used her as a symbol of the old regime’s corruption, which made her an easy target for public anger.

Where is Marie Antoinette’s last note kept and can I see it?

Marie Antoinette’s final letter is preserved in French archives, and authenticated copies or the original are occasionally loaned to museums. It has been displayed in exhibitions such as the Marie Antoinette show at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Whether you can see it at a given time depends on current exhibitions and loan arrangements.