“God Almighty has set before me two great objects, the suppression of the slave trade and the reformation of manners.” – William Wilberforce

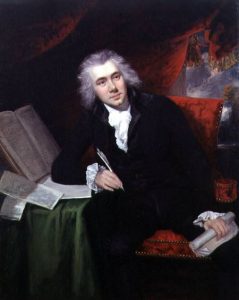

Last time on History’s Badasses, we covered Sir Christopher Lee. This time, we’re turning back the clock on one of the most influential men in English history. This man doesn’t get talked about enough, and he really should be talked about more, because long before Abraham Lincoln ever signed The Emancipation Proclamation, William Wilberforce spent his life in pursuit of eradicating the slave trade all across the British Empire. He was friends with Prime Minister William Pitt, contemporaries with King George III, and a student during the American Revolution. He was an activist, philanthropist, and active voice in the English House of Commons for his entire life. But, who was he? And what led a man who had everything to lose to throw away his health, political reputation, and life, to go after one of the most notorious institutions the British Empire ever created, at a time when to do so was utterly unthinkable?

William Wilberforce was born in Yorkshire. As a young boy, he had an incredible religious fervor that actually worried his mother and grandfather. They sent him away to school, and, by the time he was a young adult at the age of 17, he’d lost all of his religious scruples entirely. He attended balls, plays, played cards, and immersed himself in a student’s social life. He stayed up late in the night, binge-drinking and gambling. Even so, he was sharp-witted, generous with his friends, and an excellent conversationalist. He made quick friends with the future Prime Minister William Pitt, and slowly, with a more studious companion, began to consider a career in politics.

He began his political career while still in university, an intern, of sorts. He was elected Member of Parliament at the very young age of 21, and sat the chair as an independent. He frequented parliament and social clubs, retaining a healthy social life, and his skill and wit only grew with age. The Prince of Wales even said that he would go anywhere just to hear Wilberforce sing. He was immensely popular, both in Parliament and out of it. His friend, Pitt, became Prime Minister in 1783, and Wilberforce became his key supporter.

At the age of twenty-four, Wilberforce was struck with a sudden fancy to tour Europe. Little did he know that this tour would eventually change his entire life. In October, 1784, one year after his friend, William Pitt, was elected Prime Minister, William traveled with his sister, mother, and the younger brother of his former headmaster. At first, nothing changed. William enjoyed his usual pastimes of gambling and card playing, but as he traveled more, he began to read a book on religion to pass the time. After that, Wilberforce began to read the Bible more, pray, and keep a private journal. Outwardly, he remained the same old Wilberforce: tactful, happy, but at the same time urging others toward faith. Inwardly, however, he was gripped with turmoil.

Wilberforce’s political ideals changed after 1784, drastically. He became well-known for advocating against animal cruelty, and pushed bills that reduced sentences for treason committed by women (a crime that, at the time, for some reason included murder of a husband). His interest in the slave trade was sparked by a meeting with James Ramsay, a ship’s surgeon-turned-clergyman, who told him of the conditions he’d witnessed aboard slave ships and plantations in Cuba. Wilberforce was appalled by what he learned from Ramsay, but apparently didn’t start moving until, three years later, a friend urged him to bring forward the idea of abolition of the slave trade in Parliament. If anyone could do it, if anyone could convince Parliament to tear down one of the singularly most profitable industries in the British Empire, Wilberforce could.

On May 12, 1787, beneath an oak tree, during a conversation with William Pitt, just eleven years after the American Revolution, Wilberforce made the decision to tear down the British Slave Trade brick-by-brick. He wrote in a journal entry that same year that “God Almighty has set before me two great objects: the suppression of the Slave Trade and the Reformation of Manners”.

He launched a campaign against the Slave Trade that would last for almost fifty years. It took his health, saw him through the death of his best friend, and almost destroyed his personal reputation in Parliament.

He and William Pitt fought alongside each other against the Slave Trade and the East India Company, gathering evidence, raising awareness of the conditions slaves were kept in under the British Empire, and putting forth bill after bill in attempts to cripple the British Slave Trade.

Wilberforce’s health started to fail in 1820, mostly due to the stress the campaign brought on him. He continued to fight, however, giving speeches in London, in Parliament, writing essays and corresponding with important officials to raise support for abolition.

Even though he had to resign from his seat in Parliament in 1824, as his health completely failed him, Wilberforce kept fighting, writing letters to those he could and supporting from the outside. He made a final speech for abolition in Kent at a public meeting in 1833. The following month, due to his influence, the British government introduced a bill for the complete abolition of slavery, formally saluting Wilberforce and his contribution in the process. Wilberforce heard of this. Just three days later, he died. He’d been hanging on, hanging on because his work that he’d begun fifty years earlier wasn’t yet finished, and finally… finally it was.

One month after his death, the British government passed the Slavery Abolition Act, destroying slavery in most of the British Empire. 800,000 African slaves were freed. It was a feat that would have never been possible if Wilberforce hadn’t thought of it first under that oak tree in Yorkshire, 1787.