“I could but esteem this moment of my departure as among the most happy of my life.” – Meriwether Lewis

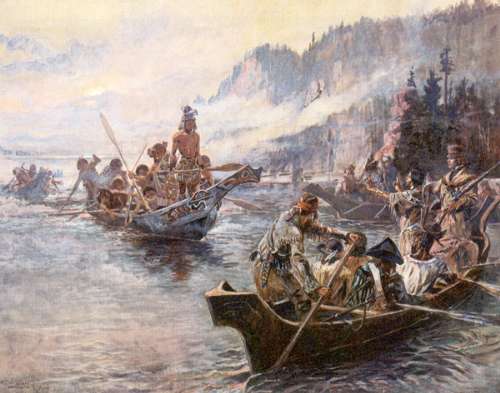

Last time, on History’s Badasses, we talked about WWII hero Jack Churchill, who’s famous for charging into battle against the Nazis armed with a claymore, a bow and arrow, and a trusty set of bagpipes. This week, we’ve got someone a little different, two someones to be exact: the famous explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, who made the trek to the Pacific Ocean entirely on foot with the help of their equally badass guide, Sacagawea.

They were sent by President Thomas Jefferson to chart the new Louisiana Purchase in 1803 and to establish America’s claim on the uncharted territory of the Northwest before Spain or Britain could. They were to study the fauna, flora, and geography and establish trade with the local Native American tribes such as the Shoshone, Nez Perce, and Plains. The trip would take them from May of 1804 to September 1806.

The Corps of Discovery

In 1803, President Jefferson formed the “Corps of Discovery”, funded by the American Congress. Meriwether Lewis was a US Army captain, and was named leader. He chose William Clark as his second in command. They made a great team. Lewis was the frontiersman and the outdoorsman. He was a strapping, brave man, who was familiar with interacting with Native American culture and had experience making decisions in a high-stress environment. Clark was a scientist in botany, natural history, minerology, and astronomy. He could accurately record everything they discovered on their way to the Pacific Ocean.

They enlisted a core of nine young men into their group, hired twenty-two more, packed up silver medals as tokens of peace to the local Native American tribes, Austrian-made weapons, flags, gift bundles, medicine, and other supplies. Once all the preparations were made, they were finally ready.

They would take the Missouri River up to its headwaters, and then they planned to ride the Colombia all the way to the Pacific Ocean. They thought that they could carry their boats easily from the headwaters to the Colombia river. They couldn’t be more wrong.

Nevertheless, at 4pm, on May 14, 1804, Meriwether Lewis, William Clark, and the Corps of Discovery left Camp Dubois and began to follow the Missouri River west. Jefferson told them:

The object of your mission is to explore the Missouri River, & such principle stream of it, as, by its course and communication with the waters of the Pacific ocean, whether the Columbia, Oregon, Colorado or any other river may offer the most direct & practicable water communication across this continent for the purpose of commerce.

– [Undaunted Courage, by Stephen E. Ambrose, p. 511]

The Journey West

They passed through what is now Kansas City, Missouri, and Omaha Nebraska. On August 20th of 1804, the group faced their first, and, miraculously, their only loss. Sergeant Charles Floyd died of appendicitis. They buried him at a bluff by the Missouri river, right by Sioux City, Iowa. Undaunted, they went on.

The expedition managed to establish good relations with two dozen Native American nations. Good thing, too, because nobody could have prepared them for the harsh winters of the Midwest, nor the treacherous, confusing climb up the Rocky Mountains. Their friends kept them from starving and guided them through the perilous climb.

Along the way, one of their horses disappeared. They believed the Sioux, or Lakota, a warring tribe that most travelers had already warned them about, had taken it. They called for a parlay. It went disastrously wrong. The Sioux asked for gifts before the group would be allowed to pass through the territory, and it almost came to blows. Eventually, both sides called off the tiff and the Corps of Discovery was allowed to pass through, unscathed.

![Reconstruction of Fort Mandan [PHOTO: wikimedia]](https://historythings.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/001_Fort_Mandan_Interior-300x200.jpg)

Reaching the Great Water

“Ocian [sic] in view! O! the Joy” – William Clark

![Mount Hood, Oregon. [PHOTO: wikimedia]](https://historythings.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/1024px-Hood85_mount_hood_and_lost_lake_ca1985-300x197.jpg)

On November 7, 1805, they first caught the site of the sparkling blue waters on the horizon. There wasn’t a lot of time to celebrate. The group was immediately faced with the challenge of winter camp. The elk had retreated, and the group was too poor to buy food from the neighboring tribes.

![Reconstruction of Fort Clatsop, Near Astoria, Oregon [PHOTO: discoverourcoast.com]](https://historythings.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/07-Fort-clatsop-1024x643.jpg)

They stayed at Fort Clatsop until March 23, of 1806, when the group, along with Charbonneau and Sacagawea, set out for home.

In the end, Lewis and Clark and the Corps of Discovery were successful. They reached the Pacific, trekking thousands of miles across harsh terrain, perilous mountains, and rushing waterfalls. They lost many of their horses, faced starvation, and many men became ill, but through it all they never lost courage, and only one man died. Their discoveries about the nature of the country of the Midwest and the Pacific Northwest and the Native American tribes living there have been invaluable to us, even today.

Meriwether Lewis died on September 3, 1809. The debate rages whether or not he was killed on the road by robbers, or had committed suicide. William Clark was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1814. He died in St. Louis, Missouri, on September 1, 1838, at the age of 68.

After the expedition, of Meriwether Lewis, President Thomas Jefferson wrote:

“Of courage undaunted, possessing a firmness and perseverance of purpose which nothing but impossibilities could divert from its direction, … honest, disinterested, liberal, of sound understanding and a fidelity to truth… with all these qualifications as if selected and implanted by nature in one body for this express purpose, I could have no hesitation in confiding the enterprise to him” (emphasis mine).”