On January 16th, 2014, as Hiroo Onoda exhaled his last breath, his battle with pneumonia ended with a heart attack. After 91 years he’d fought many battles. What made this last one easier than the others were the marching orders. He was no longer under strict orders stay alive.

With directives to collect as much intelligence as he and his men could, until such time that the Japanese could send orders to lay down their arms, Onoda and his men did just that.

As a testament to confirmation biases everywhere, Onoda’s team would perceive every signal that they could stop fighting as a trick. That bias would leave Onoda in hiding for almost thirty years, collecting intelligence, fighting a perceived enemy.

Marching Orders

When World War II called Onoda to service, he had been working in China. He was only 18 years old.

As the child of a family with a history steeped in the samurai tradition, even Onoda’s father a sergeant, there was no question what path Onoda would take. At age 18 he returned to Japan, then enlisted in the Imperial Japanese Army Infantry.

In 1944, his superiors ordered Onoda to do something they would not normally advise a Japanese soldier. They ordered him not to die, at any cost, not even capture.

In Japanese war tradition at the time, it was better to commit suicide than suffer capture. Onoda was to allow neither. Instead, he would gather intelligence for the Japanese on Lubang Island in the Philippines.

Hiroshima & Nagasaki

Onoda joined other Japanese forces in the Philippines in late 1944. By February of 1945, the United States infiltrated the Philippines. Most of the men in Onoda’s unit died or surrendered at the hands of the US soldiers.

Not Onoda. He and three other men, under orders from recently promoted Lieutenant Onoda, fled into the hills. Because of this, those four Japanese soldiers would not receive word of what happened next.

August 1945, the end of the war for Japan came when the US dropped the only two nuclear bombs ever detonated on foreign soil. Outgunned, Japan surrendered.

Onoda and the three other soldiers did not.

29 Years of Confirmation Bias

From the time Onoda received his last orders, in ’45 until ’74, he held out.

At first, the men carried out guerrilla operations. They even engaged local police in shootouts, believing they were “the enemy.”

After the surrender of Japan, Filipinos left leaflets in places where these renegade guerrillas would find them, announcing that the war was over. Onoda and his men did not believe it.

They took the leaflets as a ruse to lure them from hiding, perpetrated but the allies. How could the war be over when the enemy was firing upon them? Further attempts to end their campaign by dropping leaflets with official orders from Japan were also scrutinized but believed to be false.

After fours years, in ’49, one of the men surrendered to the Filipino forces leaving just three men in hiding. In ’54, a search party shot a man in the group, dropping their group to just Onoda and one ore. In ’72, during another exchange, police shot the other man.

After that, it was just Onoda.

Norio Suzuki

In 1974, a man named Suzuki went looking for Onoda.

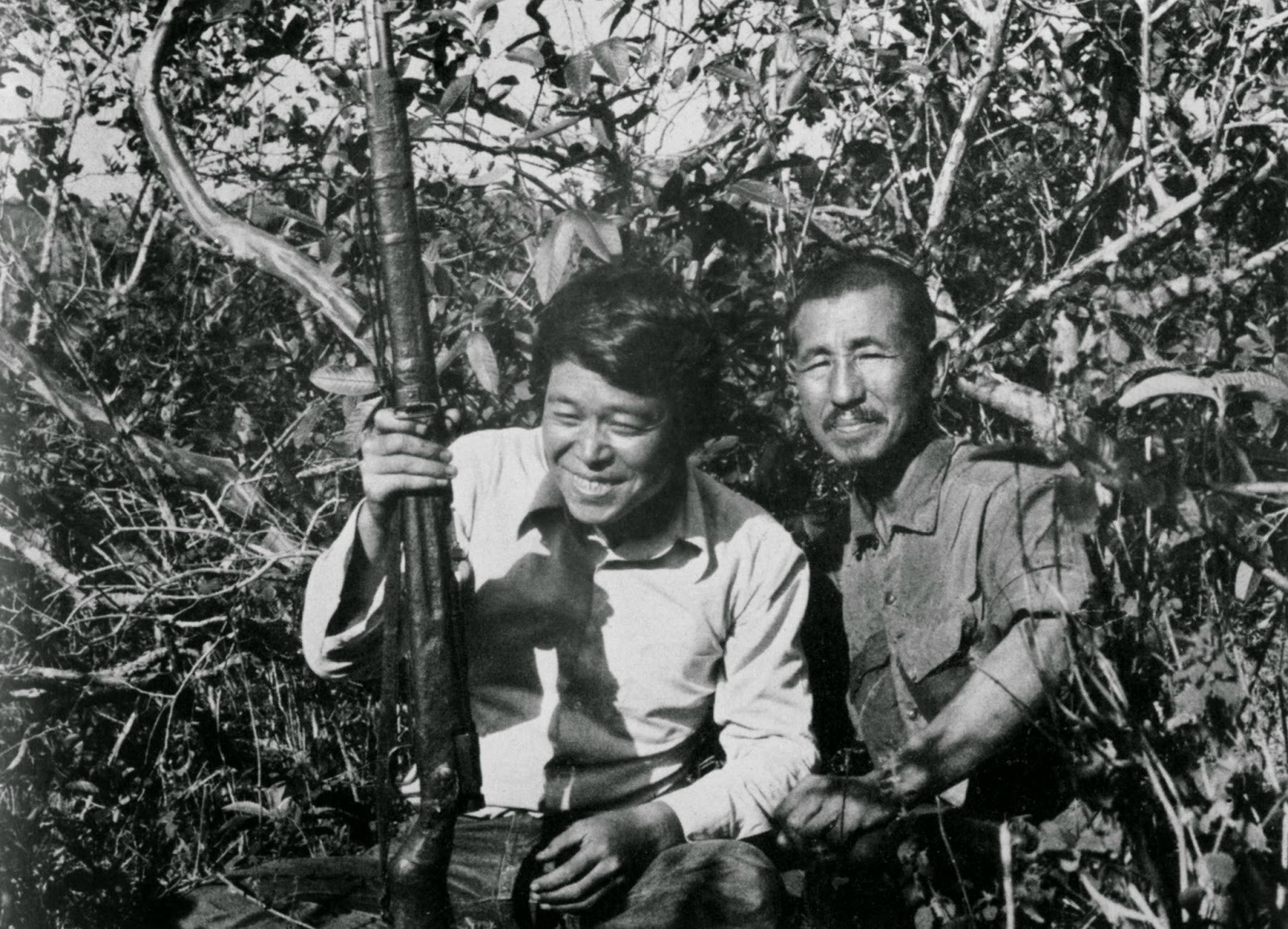

Officials had declared the Lieutenant dead since 1959 for official reasons, but no-one had yet confirmed it. After four days searching in the hills, Suzuki found and befriended him.

Despite his pleadings and the trust developed between them, Onoda would not accept what Suzuki told him.

With no other options, Suzuki left Onoda in hiding but left with a picture of them together. He took the photo to Japan, where he was able to track down Onoda’s commanding officer, Major Yoshimi Taniguchi.

The Major flew to Labang to meet with Onoda and finally declare the mission over. Onoda finally laid down his sword.

Suzuki’s efforts and the actions of Taniguchi worked. The president of the Philippines pardoned Onoda and he returned to Japan a war hero.

The simple island he had left behind, Japan, blossomed into skyscrapers, cars, and technology. The culture of people he once knew had changed. It was too much for Onoda.

He lived his the rest of life, for a period of time in Brazil, but eventually moved back to Japan until his death in 2014.