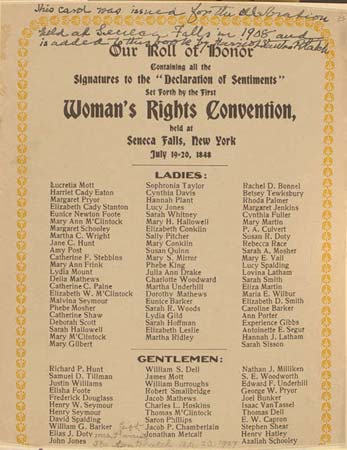

The Seneca Falls Convention, held on July 19 to July 20, 1848, was the first ever women’s rights convention. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, and other female Quakers in the area organized the meeting. It was made up of six sessions throughout the two days. The Declaration of Sentiments, which was mainly penned by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, was modeled after the Declaration of Independence and outlined the rights that American women should be given. it was signed by 100 people, mostly women. Overall, about 300 people attended the convention.

Abolitionist and women’s rights advocate Lucretia Coffin Mott met with her sister Martha Coffin Wright along with Jane Hunt, Mary Ann M’Clintock, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton on Sunday July 9, 1848 after a Quaker service in Seneca Falls. There is a possibility that M’Clintock’s daughters Elizabeth and Mary Ann, Jr were at the meeting as well. While all the other women were Quakers, Stanton was not. She told the others about her longtime frustration about a woman’s place in society over tea. From there, the five women decided to hold the first women’s rights convention right away in Seneca Falls.

Immediately they drew up an announcement for the Seneca Falls Courier that began with “WOMAN’S RIGHTS CONVENTION.—A Convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman”. It was specified on the notice that only women were permitted to attend the meetings on the first day, July 19th. Men were allowed to attend on the second day as well to hear Lucretia Mott and other speak.

The announcement first appeared on July 11, 1848. This gave people only eight days to prepare before the convention began. Frederick Douglass’s North Star also ran the notice, which was printed on the 14th. The convention was to be held in Seneca Falls at the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel. The chapel had hosted many earlier reform lecturers and was the only large building in the area that would allow a women’s rights convention.

Two days before the convention on Sunday the 16th, a small planning session was held at the M’Clintock’s home. Mary Ann M’Clintock was accompanied by her eldest daughters Elizabeth and Mary Ann, Jr. to discuss the resolutions to be presented at the convention with Stanton. Each of the women at the meeting had made sure that they voiced any appropriate concerns they had with their ten resolutions.

The resolutions demanded that women should be given equal rights in the family, religion, education, moras, and jobs. The Declaration of Independence was selected as a model for the convention’s declaration by one of the M’Clintocks. In the parlor at a round, three-legged, mahogany table, they drafted the Declaration of Sentiments. To make it more fitting for women, Stanton switched around a few of the words from the Declaration of Independence. “The history of the present King of Great Britain” was modified to say “The history for mankind” instead, for example. The second half of the Declaration of Sentiments was composed with a list of grievances.

Stanton edited the grievances and resolutions from July 16-19 at her writing desk at home. Her husband and local lawyer and politician, Henry Brewster Stanton, helped to support the document with finding “extracts from laws bearing unjustly against woman’s property interests.” Stanton added a more radical point to the list of grievances on her own, the issue of women’s suffrage and voting rights. “He has never permitted her to exercise her inalienable right to the elective franchise,” she added. Afterwards, Stanton coped the Declaration and resolutions into the form of a final document to present at the convention. Henry Stanton, when seeing her points on women’s suffrage, said to his wife, “you will turn the proceedings into a farce.” Henry Stanton was against women’s voting rights and left Seneca Falls before the convention so he would not be associated with the cause shortly before running for an elective office. So, Stanton asked her sister Harriet Cady Eaton to attend the convention with her. Eaton and her son Daniel accompanied Stanton.

A few days before the convention began on July 16, Lucretia Mott sent Stanton a note apologizing that her husband James Mott was feeling “quite well” and could not be in attendance of the convention on the first day. Instead Mott brought her sister Martha Wright, who would be able to participate in both days.

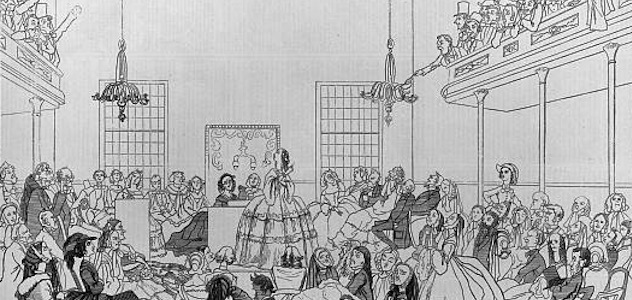

Shortly before ten o’clock, the organizing committee met at the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel on July 19, 1848. When they arrived, they found a large crowd gathering outside the chapel, which was locked. It was hot, and sunny. Daniel, Stanton’s young nephew, was lifted through an open window and was able to open the doors from the inside. While the first day was announced as exclusive only for women, some women brought children of both sexes along with 40 men expecting to attend. Though the men were not turned away, they were asked to keep silent. Appointed secretary, Mary Ann M’Clintock took notes.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was the first speaker at 11 o’clock that morning. She encouraged for the women in the audience to accept responsibility for their own lives, understanding “the height, the depth, the length, and the breadth of her own degradation.” Next, Lucretia Mott spoke. She urged all in the audience to take up the cause. Afterwards, Stanton read the entire Declaration of Sentiments, then going back and re-reading each paragraph to discuss it at length and incorporating any necessary changes. They discussed whether or not they should ask for signatures from men, of which the vote was favorable for. The signing of the declaration was put on hold until the following day so the men could participate. And at 2:30 p.m. the first session of the convention adjourned.

An afternoon session began after a pause was taken for refreshments in the 90° weather. Once again the Declaration of Sentiments was read and they added even more changes. There were then eleven resolutions on the document that were read and discussed aloud. Martha Wright wrote a humorous newspaper piece that was read by her sister Lucretia Mott. In her piece, Wright questioned why an overworked mother was the one always given written advice even as she completed the daily tasks required of her and not her husband. The twenty-seven year old Elizabeth W. M’Clintock delivered a speech before the first day was called to a close.

The evening meeting was open to all persons. Lucretia Mott addressed a much larger audience and spoke of other reform movements progressing, framing the struggle of women’s rights for the audience. Mott asked for the men to help women gain the equal rights they deserved. Mott’s evening speech was reported as “one of the most eloquent, logical, and philosophical discourses which we ever listened to,” by the editor of AUburn, New York’s National Reformer.

An even larger crowd came to the convention on July 20, 1848, the second day of the convention. More men were also in attendance. Amelia Bloomer, who arrived late, had to take a seat in the upstairs gallery. James Mott was also well enough to attend that day, chairing the morning meeting. At the time, the concept of a woman acting as a chair in front of both men and women was far too radical.

Lucretia Mott opened the meeting, reading the proceedings of the previous day, and Stanton followed by presented the Declaration of Sentiments. When she read the grievance “He has taken from her all right in property, even to the wages she earns,” Assemblyman Ansel Bascom quickly stood up and informed her that the New York State Assembly had recently passed the Married Woman’s Property Act, speaking of this at length. Frederick Douglass, Thomas and Mary Ann M’Clintock, and Amy Post made comments as well as they continued discussing the Declaration. In the end, the document was unanimously adopted. Two sections of signature’s were made, one for women, and one for men. 100 of the 300 present at the convention signed the Declaration of Sentiments. 68 of these 100 were women and 32 were men.

Again, the eleven resolutions of the Declaration were read at the afternoon session and voted on individually. Stanton’s addition of women’s rights was the only resolution that was continually questioned. Those against it argued that more rational resolutions would lose support. Only social, civil, and religious rights of women should be addressed, others argued. Both Lucretia and James Mott were against it as well. However, Stanton defended women’s suffrage, arguing that women should be given the rights to affect future legislation and gain even further rights.

The only African American at the convention was Frederick Douglass, who stood up and eloquently spoke in favor of Stanton’s addition on women’s suffrage. He said that as a black man, he could not accept the right to vote himself unless women were also given the right. Douglass also said that if women were involved in the political sphere, the world would be a better place. His powerful words rang true with most in the audience, leading the resolution to be passed by a large majority. To close the session, Lucretia Mott spoke.

“In this denial of the right to participate in government, not merely the degradation of woman and the perpetuation of a great injustice happens, but the maiming and repudiation of one-half of the moral and intellectual power of the government of the world.”

For the evening session, Thomas M’Clintock served as the chair and it was opened at 7:30 p.m. After the minutes were read, Stanton defended the many severe accusations that had been brought up against the “Lords of Creation”. Thomas M’Clintock read many of Sir William Blackstone’s laws after Stanton spoke, exposing the audience to the basis of women’s current legal condition of the servitude of men.

Lucretia Mott then stood to propose another resolution. “Resolved, That the speedy success of our cause depends upon the zealous and untiring efforts of both men and women, for the overthrow of the monopoly of the pulpit, and for the securing to woman an equal participation with men in the various trades, professions and commerce.” It was passed as the twelfth resolution.

Briefly, Mary Ann M’Clintock, Jr. spoke to all upon woman to arouse from the lethargy and be true to herself and her god. Douglass spoke next in support of the cause of woman. Afterwards, Lucretia Mott spoke for an hour, one of her “most beautiful and spiritual appeals”. While her reputation as a speaker did draw the audience, she recognized Stanton and Mary Ann M’Clintock as the convention’s “chief planners and architects”.

A committee was appointed to edit and publish the proceedings of the convention to close the meeting. On this committee was Eunice Newton Foote, Elizabeth W. M’Clintock, Mary Ann M’Clintock, Amy Post, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

The convention was met with some positive and some negative reports in local newspapers. The conventions “forms an era in the progress of the age; it being the first convention of the kind ever held, and one whose influence shall not cease until woman is guaranteed all the rights now enjoyed by the other half of the creation—Social, Civil, and Political,” The National Reformer concluded. On the other hand, the Oneida Whig was against the convention, writing that “This bolt is the most shocking and unnatural incident ever recorded in the history of womanity. If our ladies will insist on voting and legislating, where, gentleman, will be our dinners and our elbows? Where our domestic firesides and the holes in our stockings?” about the Declaration. Not only did local newspapers talk about the convention though. Soon it was gaining coverage across the country with varied reactions.

Those who had signed the Declaration of Sentiments hoped that a series of women’s rights conventions would follow. Two weeks later, the Rochester Women’s Right Convention was organized because the famed Lucretia Mott was to stay in Upstate New York for longer than planned. Mott was the convention’s featured speaker. But unlike the Seneca Falls Convention, Abigail Bush, a woman, was elected as its presiding officer. Throughout the next two years, more local and state women’s rights conventions were held in Indiana, Ohio, and Pennsylvania.