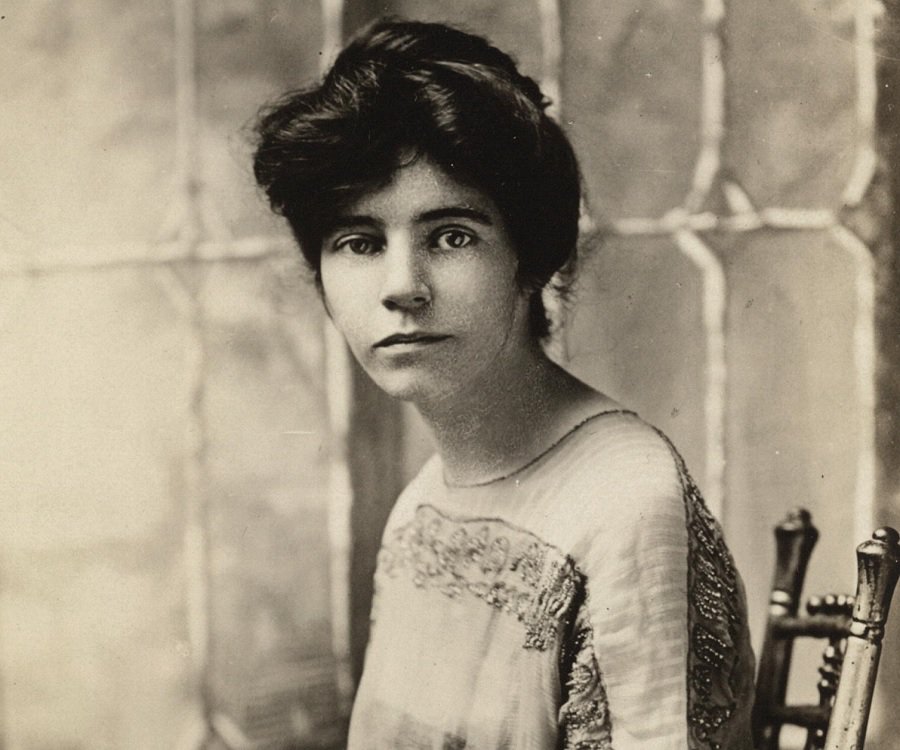

Alice Paul was a prominent women’s right activist and suffragist. Paul was the main leader of the campaign for the Nineteenth Amendment, passed in 1920, which allowed women to vote. In 1916, she cofounded the Congressional Union and the National Woman’s party. Throughout her life, she continued to campaign for equal rights for women.

On January 11, 1885, Alice Paul was born in Mount Laurel Township, New Jersey, the eldest of William Mickle Paul and Tacie Parry Paul’s four children (William, Helen, and Parry Paul). The Paul’s were descendant of William Penn, who had been the Quaker founder of Pennsylvania. Alice Paul grew up in the Quaker tradition of public service. Her mother, a member of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, was the first to teach Alice about women’s suffrage, as Quakers believed that all people, men and women, were equal in the sight of God. On occasion, Paul would attend suffragist meetings with her mother.

Graduating at the top of her class, Paul attended Moorestown Friends School in Moorestown Township, New Jersey before leaving for the Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania, which her grandfather had founded. She served on the Executive Board of Student Government while at Swarthmore. This experience may have been the spark for her later career in political activism. In 1905 with a bachelor’s degree in Biology, Alice Paul graduated from Swarthmore College.

After her graduation, Paul spent a year as a fellowship at a New York City settlement house. This was partially to avoid having to go into a teaching career. Paul learned of the injustice in America during her time at the settlement house, making her want to fix these injustices. She realized that to achieve her goal, social work was not going to do it.

In 1907, she complete coursework in political science, sociology, and economics, earning her M.A. from the University of Pennsylvania. Paul went on to complete her studies in Birmingham, England at the Woodbrooke Quaker Study Centre. At the same time, she was making a living through social work. She heard Christabel Pankhurst, a prominent suffragist in England, speak at Birmingham for the first time. Upon moving to London for work, Paul joined with Pankhurst and her mother, Emmeline Pankhurst, in the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). She was arrested several times during suffrage demonstrations and even served three terms in jail. By 1910, she had returned to the U.S. from England to continue studying at the University of Pennsylvania and earned a Ph.D. in sociology. Later, she would receive an LL.B, a law degree, from the Washington College of Law at the American University in 1922 after the 20th Amendment had been passed two years prior. Still at the American University, Paul earned an LL.M in 1928 along with a Doctorate in Civil Laws.

Up until her move to Washington in 1912, Paul had led an active social life. She dated some men and made close friendships with many women and men. Two friends she had met early on during her work or suffrage, Elsie Hill and Dora Kelley Lewis, remained her close friend for the rest of their lives. William Parker, a scholar she knew from the University of Pennsylvania, perhaps proposed marriage to her in 1917.

Paul had become deeply involved in British women’s suffrage when she moved to England in 1907. When she saw Christabel Pankhurst speak at the University of Birmingham, Paul knew that she wanted to devote her time to the women’s suffrage movement. First, she sold a suffragist magazine on street corners, which opened her eyes to the abuse most of the women involved with the movement faced. Along with Professor Beatrice Webb’s teaching, Paul kinds that social and charity work would not help her to achieve her goals of making the necessary changes in society, and instead knew she had to work towards equal legal status for other women.

When she moved to London in 1906, she became more heavily involved with the women’s suffrage movement when she joined the Women’s Social and Political Union where she often participated in both demonstrations and marches. Fellow American activist Lucy Burns met Paul in London and the two of them became friends and allies for the rest of the fight for suffrage. Both of them earned trust from major members of the WSPU as they took on organizing events. They also accompanied Emmeline Pankhurst to Scotland as her assistants. In Edinburgh, Paul and other suffragists planned to protest Sir Edward Grey’s, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, speech. They spoke with locals on the streets for a week up to the event to notify them of the protests. During the meeting once Grey had spoken about his proposed legislation, Paul jumped up and said “Well, these are very wonderful ideals, but couldn’t you extend them to women?”. In response, the police dragged her out of the building and to the police station to be arrested. Many viewed this act as silencing legitimate protests, resulting in an increase of press coverage on the women’s suffrage movement and public sympathy.

To address the gathering crowd below, Paul camped out on the roof of St. Andrew’s Hall in Glasgow in August of 1909 before a political meeting was to take place. The police forced her to get off the roof, but the crowds cheered her on for her efforts. Along with other suffragettes, Paul and Burns tried to enter the event, but were then beaten by the police. Bystanders attempted to protect them out of sympathy. Paul and the other fellow protesters` were taken into custody as crowds began to gather outside the police station to demand their release.

In honor of Lord Mayor’s Day, the lord Mayor of London hosted a banquet on November 9, 1909 for cabinet ministers in the Guild Hall in London. Paul worked hard on planning the WSPU’s response to the event. With Amelia Brown, she was disguised as a cleaning woman and was able to enter the building with the normal staff. The two of them hid in the building until the event was to start in the evening, as they had entered around 9:00 a.m. As Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith began to speak, Brown threw her shoe through a stained glass pane. Both her and Paul cried out, “votes for women!” as Brown threw her shoes. They were both arrested after the event, sentenced to one month of hard labor because they refused to pay any fines and damages. Eventually Paul would come to be arrested a total of seven times and imprisoned three times during her time with the WSPU.

During her time in prison, Emmeline Pankhurst taught Paul the tactics of civil disobedience. One of the many tactics was to demand to be treated as a political prisoner when arrested. While this sent a message to the public about the legitimacy of suffragists, it also came with possible tangible benefits. Political prisoners were given special status in most European countries, England included. These benefits of a political prisoners included that they were not searched when arrested, not kept with other prisoners, not force fed, and not required to wear prisoner’s clothing. The WSPU gained a lot of press due to their civil disobedience when it came to this, despite the fact that most of the time, the members were not granted the status of political prisoner. Paul refused to wear the garb of a prisoner when she was once arrested in London and not given the status of a political prisoner. The prison matrons were unable to undress her, requesting the guards’ assistance. Even more press came from this improper act.

That was not the only tactic the suffragettes used. Another was hunger striking, which was first conducted by WSPU member and sculptor Marion Wallace Dunlop in June of 1909. WSPU members began increasingly using the tactic by that fall because it was effective in getting more publicity for their mistreatment. It also gained quick release from prison wardens. Paul refused food during her first two arrests, but during the third, the warden made sure she was force-fed twice a day to keep her strong enough for her month’s sentence. But along with other women, Paul described hunger striking as torturous. And by the end of that month spent in prison, Paul had developed severe gastritis. Immediately they carried her out of the prison to be treated by a doctor. This left her health permanently damaged. For the rest of her life, she frequently caught colds and the flu, sometimes leading to hospitalization.

Paul made her way back home to January 1910 after her last imprisonment in London to continue recovering and to develop a plan towards suffrage in the U.S. The American media and news quickly began following her when she returned after being well-publicized in England. Paul soon decided that she was to embrace one single goal as a testimony, recognizing women as equal citizens.

To pursue a Ph.D., Paul re-enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania and began speaking about her experiences in England in the British suffrage movement to other Quakers. She also began her work towards suffrage in the U.S., but on a more local level. Paul’s dissertation was an overview of the history of legal status for women in the United States. Afterwards, she began to participate in rallies led by the National Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). She was then invited to speak at NAWSA’s annual convention in April of 1910. Paul and Burns proposed a leadership campaign to NAWSA for a federal amendment that gave women voting rights. However, this was contrary to NAWSA’s strategy of going state-by-state. The two of them were laughed at by the members of the NAWSA, with the exception of Jane Addams. Addams suggested they tone down their plan. Paul requested she be placed on the Congressional Committee of the organization in response to this.

Organizing and initiating the Woman Suffrage Procession in Washington the day before President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration was her first big project. Paul was determined to make Wilson feel pressured, as he would have the most influence over Congress. Volunteers were assigned to contact suffragists from across the nation and to find supporters to march in their parade. After only a few weeks, she had succeeded in gathering about 8,000 people to march to represent most of the country. It was much harder to gain support from institutions for the parade though. She insisted that the parade go before Wilson on Pennsylvania Avenue. The goal of this march was to sent Wilson the message that women’s suffrage did exist and it would outlast him if necessary.

Originally, D.C. officials resisted the route and Paul was the only person who truly believed that it would keep going on that route, says biographer Christine Lunardini. The city would eventually allow NAWSA to follow the planned route. More troubles continued as City Supervisor Sylvester claimed that marching along Pennsylvania Avenue was not a safe route for the women, instead suggesting that they move the parade somewhere else. In response, Paul demanded that more police be provided for the march, but Sylvester did not comply. Congress passed a special resolution that ordered for Sylvester to prohibit any regular traffic along the route on March 13, 1913.

The march went down the original route Paul had desired. Inez Milholland, a well known labor lawyer, dressed in white and rode a horse as the parade’s leader. Not only did women march through D.C., but they were also accompanied by floats, bands, banners, squadrons, and chariots to represent the lives of all women. The lead banner, which stated “We Demand an Amendment to the United States Constitution Enfranchising the Women of the Country.”, was perhaps the most notable sight. The parade was viewed by over half a million people, but sufficient police protection was not provided, leading to the parade nearly turning into a riot. Onlookers pressed so close to the women, making them unable to keep going down the parade route. Police did not do much to save the women from the rioters either. Later on, a senator who had participated in the parade testified that he had taken 22 officers badges as they stood idle. The Massachusetts and Pennsylvania national guards and Maryland Agricultural College students eventually stepped in to make a human barrier so the women could pass. Some people even said that Boy Scouts jumped in to provide first aid to any women injured. Due to this incident, more awareness and sympathy was given to the NAWSA because of the police’s response to the parade.

The NAWSA focused on lobbying for an amendment to the constitution after the parade to give all women voting rights. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton and fought for this amendment year prior as leaders of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA).

However, Paul’s methods created tensions between her and the NAWSA’s leaders. They believed she was moving too aggressively in Washington, leading to disagreements about strategy and tactics. This then led to the breaking up of the NAWSA. Paul went on to form the Congressional Union for Women’s Suffrage and the National Woman’s Party (NWP) in 1916. The NWP introduced methods that had been used in the British suffragist movement and it focused on a constitutional amendment that granted lal women voting rights. Multi-millionaire socialite Alva Belmont was paul’s largest donor. The weekly Suffragist and press coverage accompanied the NWP.

In the western states, Paul campaigned with the NWP during the US Presidential election to go against Wilson’s continuous refusal to support a suffrage amendment. Their main reason for campaigning in the west was because women in these states already had voting rights. The NWP staged their first political protest in January of 1917 at the White house. The pickets held banners demanding voting rights at the nonviolent civil disobedience campaign called the “Silent Sentinels”.

Many people began to view the Silent Sentinels as disloyal when the United States entered the Great War in April of 1917. Picketers were arrested for “obstructing traffic” that June. For the next six months to come, Paul and many other picketers were incarcerated in Virginia at the Occoquan Workhouse and the District of Columbia Jail.

Some of the public was surprised when they learned of the news of the leading suffragists going to prison for peaceful protests. Wilson was given bad publicity because of this and he was livid that he had been forced into such a position. Two days after the women had been sentenced, he pardoned the first women, but this did not put an end to their arrests and abuse.

After Wilson pardoned the suffragists, they continued picketing outside of the White House with banners that read slogans like, “Mr. President, How Long Must Women Wait for Liberty?”. Despite their peaceful protests, they were opposed violently. Young men beat and harassed the women who protested, and the police never intervened to save the women. Sometimes, the police would arrest men who tried to help the women when they were beat. The suffragists gained public support through their peaceful protests, despite that this was all going on while the country was at war. However, more and more protesters were sent to either Occoquan or the District Jail and Wilson no longer offered pardons.

On October 20, 1917, Paul started a seven-month jail term in the District Jail. Her and other activists in the NWP had purposely tried to receive these sentences. The women were never given special treatment as political prisoners, living in poorly sanitized harsh conditions with infested food. Paul began a hunger strike in protest of the District Jail’s conditions. Instead, they moved her to the psychiatric ward and force-fed her raw eggs through a feeding tube.

Becoming known as the “Night of Terror”, the suffragists at Occoquan endured brutal treatment on November 14, 1917. To protest the treatment of the suffragists, the NWP went to court. As Paul was suffering, the women at Occoquan were moved to the District Jail. Paul experienced brutality, but remained brave and undaunted. Finally, all the suffragists were released from prison on November 27-28, 1917.

Along with continuous demonstrations and Paul’s hunger strike, press coverage kept Wilson and his administration pressured. Wilson began to strongly urge Congress to pass legislation allowing women to vote in January of 1919. The NWP put an end to their picketing in response., but returned once again when the Senate failed to pass the amendment later that September. They began staging more confrontation demonstrations afterwards in the winter of 1918-19. Women in the NWP would climb statues, burn “watch fires” in front of the White House while Wilson was in Versailles, and chained themselves to fences. The women also set fire to banners with his words on democracy from the Peace Conference.

The Senate finally passed the suffrage amendment in June of 1919, and now the state legislatures had to ratify it. In August of 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment was finally ratified and passed. Eventually, every single state (With the exception of Hawaii and Alaska, as they had not been states at the time), would ratify the amendment. The amendment nearly didn’t get passed because the Tennessee Assembly was short one vote, until Assemblymember Harry Burn changed his vote when his mother sent him a telegram asking him to.

Alice Paul was the Equal Rights Amendment’s original author in 1923. It was passed in 1972 by the House and the Senate, but only thirty-five states voted in favor of the amendment in time for the deadline instead of the required thirty-eight. To this day, efforts are being made to revive the ERA.

In the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Paul played a major role later in her life to give women more protection. Powerful Virginian Democrat Howard W. Smith added a prohibition on sex to the Civil Right ACT. His amendment was passed in the House with a vote of 168 to 133. Smith sponsored the Equal Rights Amendment for twenty years in the House. He believed in equal rights for women, but opposed equal rights for African-Americans. Smith had also been close with Paul and the NWP. She had worked with him since 1945 to find a way to include sex as a protected civil right.

Until Paul suffered from a stroke in 1974, Paul continued her work towards equal rights for women. At ninety-two years old, Alice Paul died on July 9, 1977 at a Quaker facility in Moorestown, New Jersey, the Greenleaf Extension Home.