At 3 o’clock on an April afternoon in 1925, a reporter from the Chicago Daily Tribune stopped a line of schoolchildren and asked a simple question: “What do you do after school hours?”

The answers were not about soccer practice, tutoring, or scrolling a phone. They were about delivering groceries, watching baby brothers, listening to the radio, and grabbing a few minutes of play on the sidewalk before dark.

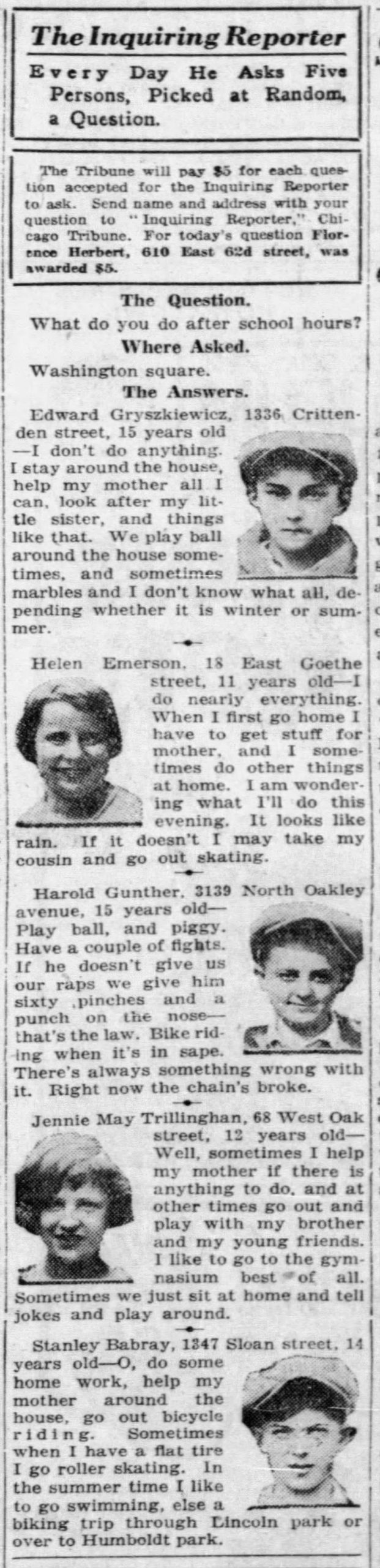

That kind of “inquiring reporter” column, printed on April 25, 1925, caught a snapshot of ordinary childhood in the interwar years. It showed what American kids actually did between the last bell and bedtime. By looking at those answers and the wider record, you get a very different picture of childhood than the nostalgic myth of endless carefree play.

Here are five things kids in 1925 really did after school, with concrete examples and why each one mattered for families, cities, and the idea of childhood itself.

1. They worked: chores, street jobs, and unpaid family labor

For many children in 1925, “after school” did not mean free time. It meant work. Some of that work was paid, like delivering newspapers or clerking in a shop. Much of it was unpaid labor for the family, from farm chores to minding younger siblings.

By the mid‑1920s, formal child labor in factories was declining, but kids’ work had not vanished. It had moved into the gray zone of “helping out” and casual street jobs.

A concrete example: look at the newsboys on any big‑city corner. In Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia, thousands of boys, often between 10 and 15, still sold papers after school. The famous 1910s “newsies” strikes had forced some reforms, but in 1925 you could still find kids like Louis “Kid Blink” Baletti’s successors hawking the Tribune or the New York World until dinnertime. Census data from 1920 show hundreds of thousands of boys listed as “newsboys, newsdealers, and newsvendors.”

In rural America, the work looked different but was just as real. A 12‑year‑old Iowa farm boy in 1925 might come home from a one‑room schoolhouse and go straight to feeding livestock, hauling water, or helping with milking. Agricultural work was explicitly carved out of many child labor laws, so parents and kids treated it as normal, not as “child labor” in the reformers’ sense.

Girls’ work was often invisible in statistics but obvious in daily life. A Chicago “inquiring reporter” column from the 1920s has a girl casually explain that after school she “helps mother with the washing” and looks after her baby sister. That kind of unpaid domestic work filled the hours between school and bedtime for countless girls, especially in working‑class and immigrant families.

Why it mattered: this after‑school work blurred the line between “student” and “worker.” Reformers could claim victory against factory child labor, yet families still depended on kids’ labor to make ends meet. The fact that so much of it happened after school helped sell the idea that America had protected childhood, even as many children were still part‑time workers in everything but name.

2. They did real housework and sibling care, especially girls

If you were a girl in 1925 and the reporter asked what you did after school, there was a good chance your answer involved a broom, a stove, or a baby.

Household labor was not just a few chores. In many homes it was a second shift. Girls in particular were expected to help with cooking, laundry, cleaning, and what we would now call childcare.

Take the example of Italian and Polish immigrant families in cities like Chicago and Cleveland. Social workers’ reports from the 1920s describe older daughters, sometimes only 11 or 12, racing home from school to start dinner before their mothers returned from factory or cleaning jobs. The girls watched toddlers, boiled potatoes, and ironed shirts while trying to squeeze in homework. One 1920s Chicago settlement house worker wrote about “little mothers” who “keep house for the family from three o’clock until their parents come home.”

Even in middle‑class homes, the expectation that daughters would learn housework early was strong. Advice columns in magazines like Good Housekeeping urged mothers to give girls regular after‑school duties so they would be “prepared for their future homes.” Boys might mow the lawn or take out the ashes, but girls were more likely to be cooking, sewing, or bathing younger siblings.

This work was unpaid, but it had real economic value. In families that could not afford hired help or daycare, an older daughter’s labor made wage work possible for parents. In effect, many girls were the invisible domestic staff of their own households.

Why it mattered: these after‑school responsibilities trained girls for a life of unpaid domestic labor and limited their time for study and play. The gendered division of after‑school hours helped lock in expectations about women’s roles, even as more women were entering paid work. It also meant that when educators talked about “the child” after school, they were often imagining a boy, not the girl stirring a pot with a baby on her hip.

3. They played outside, mostly unsupervised and in the street

Not every child went straight from class to work. For many, especially boys in cities, the first stop was the street, the vacant lot, or the nearest park.

Children’s play in 1925 was typically outdoors, improvised, and adult‑free. There were no organized soccer leagues on every corner. There were stickball games, marbles, jump rope, sandlot baseball, and elaborate neighborhood “gangs” with their own rules.

In New York’s Lower East Side, kids turned tenement courtyards and alleys into makeshift playgrounds. Jacob Riis’s earlier photos show this world, and by the 1920s it had not gone away. A boy might tell the inquiring reporter that after school he “plays ball” or “runs with the fellows.” That could mean anything from a casual game to roaming several blocks away, out of sight of any adult.

Reformers worried about this. The playground movement, which had grown since the early 1900s, pushed cities to build supervised play spaces. Chicago’s progressive reformers helped create the South Park playgrounds, and by 1925 many schools had some kind of yard or gym. Yet kids still preferred the freedom of the street. Police and social workers complained about “gangs of boys” hanging around pool halls and street corners between 3 and 6 p.m.

Girls played too, but their range was often smaller. They jumped rope on the sidewalk, played hopscotch, or gathered on stoops to play jacks and clapping games. The street was a social world, a place to trade gossip and candy, not just to burn off energy.

Why it mattered: these unsupervised hours shaped neighborhood culture and fed adult fears about delinquency. The gap between how kids actually used the streets and how reformers wanted them to use playgrounds drove new policies on juvenile courts, curfews, and recreation programs. The after‑school street scene became a battleground over who controlled children’s time and space.

4. They discovered new media: radio, movies, and cheap fiction

By 1925, a new kind of after‑school activity was creeping into American homes and downtowns: media consumption. Kids listened to the radio, went to the movies, and devoured cheap magazines and comic strips.

Radio was the big newcomer. In 1922 there were only a few hundred stations. By 1925 there were more than 500 across the United States. Families that could afford a set often gathered around it in the late afternoon or evening. While many children in 1925 still had no radio at home, those who did might rush home after school to catch music or early children’s programs.

One example: in Chicago, station WGN, owned by the Chicago Tribune, began experimenting with children’s programming in the 1920s. Kids wrote letters to radio hosts, entered contests, and formed “radio clubs.” Even if the timing skewed toward evening, the excitement carried into the after‑school hours as kids talked about what they had heard and planned to tune in again.

Movies were even more established. Nickelodeons had been around since the 1900s, and by the mid‑1920s, neighborhood movie theaters were common. A child in 1925 might spend Saturday after school at a matinee, watching a silent comedy with Charlie Chaplin or a Western starring Tom Mix. In some cities, theaters offered cheap weekday afternoon shows that drew in kids once their classes ended.

Print culture filled the gaps. Boys’ adventure magazines like The American Boy and dime novels about detectives and cowboys were widely read. Newspaper comic strips, from “Little Orphan Annie” (which debuted in 1924 in the Chicago Tribune) to “Mutt and Jeff,” gave kids daily serialized stories that they might catch up on after school.

Parents and reformers were ambivalent. They worried that movies and “trash fiction” would corrupt morals or distract from homework. Censorship boards and “clean movies” campaigns were partly a reaction to the sight of children streaming into theaters after school.

Why it mattered: these new media began to standardize childhood culture across regions and classes. A kid in Chicago and a kid in Kansas could laugh at the same Chaplin gag or follow the same comic strip hero. After‑school hours became a key market for entertainment industries, which would later target children even more directly with radio serials, comic books, and, eventually, television.

5. They went to clubs, churches, and settlement houses for ‘safe’ time

Adults in 1925 were not blind to the fact that kids had several loose hours between school and bedtime. Reformers, churches, and civic groups tried to fill that time with supervised, “uplifting” activities.

After‑school clubs and programs were a growing part of urban childhood. Settlement houses, YMCAs, YWCAs, and church basements hosted reading rooms, gym classes, sewing circles, and boys’ and girls’ clubs that met right after school.

Hull House in Chicago, founded by Jane Addams, is a clear example. By the 1920s it ran clubs for children and teenagers that met in the late afternoon. Kids could take art or music lessons, join drama groups, or use the gym. The idea was to keep them off the streets, help immigrant children “Americanize,” and provide some recreation that was not just work or wandering.

Religious groups joined in. Catholic parishes in cities like Boston and New York organized after‑school catechism classes, youth sodalities, and sports teams. Protestant churches ran “Christian Endeavor” societies and boys’ brigades. The Boy Scouts and Camp Fire Girls, both founded in the 1910s, held meetings that often started soon after school let out, teaching badges, camping skills, and a particular moral code.

For rural kids, 4‑H clubs, which were expanding in the 1920s, offered after‑school and weekend activities focused on agriculture, home economics, and “character building.” A farm boy or girl might head to a neighbor’s barn or the local schoolhouse for a 4‑H meeting after chores and classes.

These programs were not neutral. They aimed to shape children’s values, habits, and identities. They taught English to immigrant kids, pushed temperance and patriotism, and tried to steer boys away from saloons and pool halls.

Why it mattered: organized after‑school programs were an early attempt to institutionalize what we now call “after‑school care.” They reflected adult anxiety about unsupervised youth and helped move childhood from the street and home into semi‑formal institutions. The tug‑of‑war between free time and structured time that defines modern childhood was already underway in 1925.

The Chicago reporter’s question in April 1925, “What do you do after school hours?” sounds casual. The answers, if you read them against the wider evidence, are anything but.

Kids in 1925 were workers and caregivers, street players and media consumers, club members and church kids. Their afternoons were a mix of responsibility and freedom that does not map neatly onto today’s schedules of organized sports, homework, and screen time.

Why it still matters: when we romanticize “simpler times,” we erase the labor and limits that shaped children’s lives a century ago. Looking closely at those after‑school hours in 1925 shows how ideas about childhood, work, and leisure were already contested. The gap between what reformers wanted kids to do and what kids actually did has never really closed. It just moved from the tenement street to the group chat and the minivan.

Frequently Asked Questions

What did kids actually do after school in the 1920s?

Many children in the 1920s worked after school at paid jobs or unpaid family labor, especially chores and sibling care. Others played outside in streets and vacant lots, went to movies, listened to the radio, or attended clubs and church programs. Their time was a mix of work, informal play, and emerging organized activities.

Did children in 1925 have homework and free time like today?

Yes, many schoolchildren in 1925 had homework, but the amount varied by school and grade. Free time existed, but it was shaped by class and gender. Working‑class kids often had less leisure because of jobs and chores, and girls were more likely to spend after‑school hours on housework and childcare rather than play.

Were kids still working as child laborers in 1925?

Formal child labor in factories had declined by 1925 due to laws and enforcement, but many children still worked. They sold newspapers, clerked in shops, helped on farms, and did significant unpaid labor at home. Much of this work happened after school, which made it easier for society to ignore it as “real” child labor.

Did children listen to the radio or go to movies after school in the 1920s?

Yes. In families that owned a radio, children often listened in the late afternoon or evening, including some early kids’ programs. Many also went to neighborhood movie theaters for matinees, especially on Saturdays. Silent comedies, Westerns, and serials were popular with young audiences and became a shared cultural experience.