On a spring day in 1925, a New York newspaper sent a photographer into the streets with a nosy little question: “Are you satisfied with the name with which you were christened?”

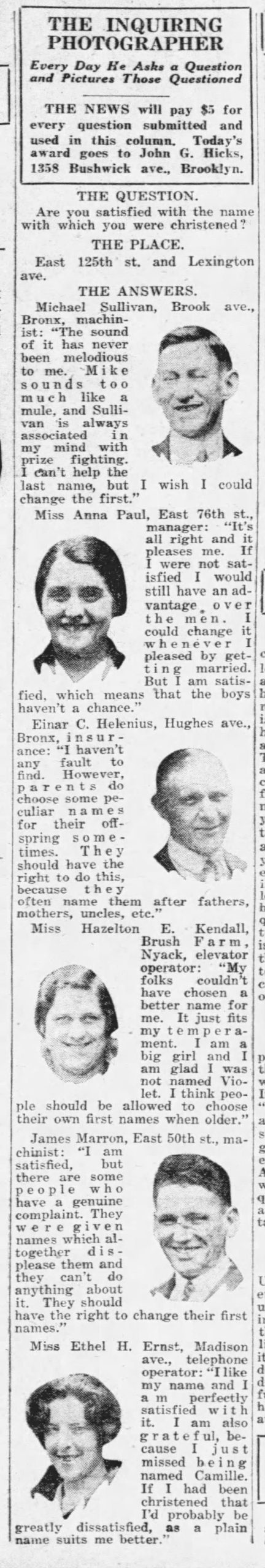

This was the New York Evening World’s “Inquiring Photographer” feature, a proto–man-on-the-street column that paired candid photos with short quotes. It usually asked about politics or baseball. On May 28, 1925, it asked about something far more personal: your own name.

On the surface, it sounded like a light question. But in a city full of immigrants, suffragists, showgirls, and strivers, a name was not just a label. It was an argument about who you were and who you wanted to be.

By looking at that one question in 1925, you can see how names tied into immigration, gender, celebrity culture, religion, and the rise of bureaucracy. Here are five things that simple street-corner survey reveals about identity in the 1920s.

1. Names Were a Battleground for Immigrant Identity

What it is: In the 1920s, millions of Americans were first- or second-generation immigrants, and their names carried the weight of where they came from. A question like “Are you satisfied with the name with which you were christened?” hit right at the tension between Old World heritage and New World pressure to fit in.

In 1925 New York, nearly 36 percent of residents were foreign-born. Italian, Jewish, Irish, German, Polish, and other communities filled the tenements and outer boroughs. Their names often announced their origins before they said a word.

Contrary to the popular myth, Ellis Island officials did not usually change immigrants’ names at the dock. Most name changes happened later, in city courts or informally at work and school. But the pressure was real. A surname that sounded “too foreign” could cost you a job interview or mark you for discrimination.

A classic example from this era is the comedian born Jacob Rodney Cohen in 1921 to a Jewish family. He grew up hearing jokes and slurs about his name and background. When he entered show business, he adopted the stage name Rodney Dangerfield. He was a bit younger than the 1925 respondents, but his story reflects a pattern that was already common: drop the ethnic-sounding first name, keep or smooth the last name, and hope for wider acceptance.

Another example from the period is Fiorello La Guardia, the future mayor of New York. Born in 1882 to an Italian father and Jewish mother, he kept his Italian given name and surname. When he ran for Congress in 1916 and later for mayor in the 1930s, his name was both a badge of pride for Italian Americans and a barrier with nativist voters. He refused to anglicize it, and his eventual success showed that an ethnic name could win elections in a city of immigrants.

Immigrant families often split the difference. Parents might keep a traditional surname but give children more “American” first names. A Polish family named Kowalski might name their son John instead of Jan. That way the family line stayed visible, but the child had a name that fit on an English-language job application.

So when the Inquiring Photographer asked if people liked their christened names, many immigrant New Yorkers were really weighing something larger: Do I cling to the name my grandparents used, or do I adopt the name my boss can pronounce?

So what? The 1925 name survey captured a moment when millions of Americans were renegotiating their identities, and immigrant names were often the first thing put on the bargaining table.

2. Women’s Names Exposed the Rules of Gender and Marriage

What it is: For women in 1925, a name was not just a personal label. It was tied to marriage, respectability, and legal status. The question “Are you satisfied with the name with which you were christened?” hit differently for women who had already been forced to change their names once they married.

By custom and law, most American women took their husband’s surname at marriage. Their maiden names often vanished from everyday use. In legal documents, a woman might be “Mrs. John Smith,” her own first name erased behind her husband’s. That made the “christened” name feel like something you lost, not something you owned.

One example from this era is the writer and activist Crystal Eastman. Born Crystal Catherine Eastman in 1881, she kept her name in her public work even after marrying twice. She wrote legal articles and feminist essays under “Crystal Eastman,” not under her husbands’ surnames. Her choice to keep her birth name in print was a quiet rebellion against the assumption that a woman’s identity should be folded into her husband’s.

Another example is Lucy Stone, a suffragist from an earlier generation, who famously kept her maiden name after her 1855 marriage to Henry Blackwell. By the 1920s, women who kept their birth names were sometimes called “Lucy Stoners.” That label carried into the new century. In 1921, the Lucy Stone League formed in New York to fight for a woman’s right to keep her name after marriage. By 1925, their arguments were circulating in the same city where the Inquiring Photographer was quizzing women about their christened names.

Even for women who did take their husband’s surnames, first names were political. The 1920s saw a surge in modern-sounding names for girls: Thelma, Mildred, Dorothy, and especially the flapper-adjacent “Gladys” and “Evelyn.” These names signaled a break from older, more biblical names like Martha or Sarah. A woman in bobbed hair and a knee-length dress named “Evelyn” sent a different message than a “Gertrude” in a high collar, even if they were the same age.

Newspapers of the time sometimes joked about “old maid” names versus “modern” names. Underneath the jokes was a real anxiety: if your parents had christened you with a stiff Victorian name, did that mark you as old-fashioned in the Jazz Age?

So what? The 1925 question about christened names exposed how women’s identities were tied to marriage law and fashion, and how some women were already pushing back by clinging to or reshaping their own names.

3. Celebrity Culture Was Teaching People to Rebrand Themselves

What it is: By 1925, Hollywood and Broadway were teaching Americans that you could reinvent yourself with a new name. Stage names and screen names were everywhere. That made the question “Are you satisfied with the name with which you were christened?” feel like an invitation to imagine a more glamorous self.

The 1920s were the first full decade of mass movie stardom. Studios wanted short, catchy, Anglo-sounding names that could fit on a marquee. Many actors obliged. The actress born Lucille Fay LeSueur, for example, entered Hollywood in the mid-1920s. MGM executives thought her name sounded awkward. In 1925, the fan magazine Photoplay held a contest to rename her. The winning entry: Joan Crawford. Her new name helped launch one of the most famous film careers of the century.

Another case is the actor born Issur Danielovitch in 1916 to Jewish immigrant parents. He grew up in New York and, like many boys in the 1920s, watched the rise of movie heroes with simple names like Tom Mix and John Gilbert. When he went to Hollywood after World War II, he changed his name to Kirk Douglas. His choice reflected a habit that had already taken hold in the 1920s: if your birth name sounded too ethnic or complicated, you swapped it for something short and “American.”

Even outside Hollywood, entertainers and hustlers were rebranding themselves. In New York’s nightlife scene, chorus girls and vaudeville performers often adopted names that sounded more refined or exotic than the ones on their birth certificates. A girl born Mary Smith might dance under the name “Mimi LaRue.” The point was not legal accuracy. It was selling an image.

Newspapers fed this trend. Gossip columns and theater pages regularly mentioned performers under their stage names, rarely noting their birth names. Readers absorbed the idea that names were flexible, especially if you were chasing fame or success.

So when the Inquiring Photographer asked passersby if they liked their christened names, they were answering in a culture where changing your name for effect was no longer shocking. It was something movie stars did, and ordinary people could daydream about.

So what? The rise of celebrity culture in the 1920s helped normalize the idea that a name was part of your personal brand, not a fixed destiny, and that made people more willing to question or change the names they had been given at birth.

4. Bureaucracy Made Names Feel Permanent, Even When People Wanted Change

What it is: While culture was telling people they could reinvent themselves, the expanding machinery of government and business was doing the opposite. In 1925, your name was increasingly tied to official records, paychecks, and legal documents. That made the question “Are you satisfied with the name with which you were christened?” more than a matter of taste. It brushed up against the growing power of bureaucracy.

The early 20th century saw a surge in record-keeping. Cities kept stricter birth records. Public schools maintained enrollment lists. Employers kept personnel files. Banks tracked accounts. The federal government had just finished drafting millions of men for World War I, a process that depended on names, addresses, and birth dates.

One example of how sticky names became is the case of Social Security, which would arrive a decade later. The Social Security Act passed in 1935, and by 1937 the government was issuing numbers tied to names. From then on, your official name mattered in a new way. But the habits that made that system possible were already in place by 1925: clerks, forms, and filing cabinets that expected a single, stable name.

Court records from the 1910s and 1920s show steady traffic in legal name changes, especially in big cities. Judges often approved requests from immigrants who wanted simpler names. A man named Giuseppe Esposito might legally become Joseph Espos. But the process required paperwork, fees, and sometimes newspaper notices. It was not as simple as just introducing yourself differently at a party.

At the same time, informal name changes were common. A boy christened “William” might be known as “Bill,” “Billy,” or even “Red” if he had the hair to match. A woman named “Margaret” might answer to “Maggie,” “Peggy,” or “Meg.” These nicknames often appeared in social columns and on calling cards, but not on legal documents.

So the people answering the Inquiring Photographer in 1925 were caught between two systems. In daily life, names were flexible and negotiable. In official life, names were becoming fixed entries in ledgers and files. If you hated your christened name, you could escape it in conversation, but not always on paper.

So what? The 1925 survey reveals a society in transition, where expanding bureaucracies were freezing names in place at the very moment individuals were feeling more freedom to reshape their identities.

5. The Question Exposed Tension Between Religion and Modern Individualism

What it is: The phrase “the name with which you were christened” was not neutral. It pointed directly to religious ritual, especially in Christian traditions where baptism or christening formally gave a child their name. Asking if you were “satisfied” with that name quietly challenged the idea that a name given in a sacred ceremony should be accepted without question.

For many Catholics, Orthodox Christians, and some Protestants, christening was a serious rite. Parents chose saints’ names or biblical names. A child might be named Mary after the Virgin Mary, or Joseph after the earthly father of Jesus. The name linked the child to a religious story and a heavenly protector.

In heavily Catholic neighborhoods of New York, it was common to see long strings of names honoring multiple saints and relatives. A boy might be christened “Antonio Giuseppe Maria” after a grandfather, a saint, and the Virgin. In daily life, he might answer to “Tony.” The nickname was modern and American. The christened name was old and sacred.

One clear example of religious naming is Alfred Emmanuel Smith, the New York politician who would run for president in 1928. His middle name, Emmanuel, meant “God with us” and reflected Catholic tradition. When he campaigned, he usually appeared as “Al Smith,” a stripped-down, friendly version of his more formal, religiously flavored full name. The split between “Alfred Emmanuel” on paper and “Al” on the stump mirrored the split many people felt between their christened names and their everyday identities.

By 1925, American culture was tilting toward individual choice. The same decade that brought flappers, jazz, and psychoanalysis also brought a new willingness to question family and church authority. Sigmund Freud’s writings were being translated into English and discussed in magazines. The idea that you had an inner self, perhaps different from the one your parents imagined, was gaining ground.

So when a newspaper asked if you liked the name given to you at your christening, it was poking at that tension. Were you bound by your parents’ religious choices, or did you have the right to rename yourself in line with your own desires?

So what? The 1925 name question captured a quiet shift from names as religious obligations to names as personal choices, reflecting the broader move from traditional authority toward modern individualism.

Put together, those street-corner answers in May 1925 were about far more than personal taste. They revealed how names sat at the crossroads of immigration, gender, celebrity, bureaucracy, and faith.

Today, people still argue with their own birth certificates. Trans people fight for the right to have their chosen names recognized by the state. Immigrant families weigh whether to give their children names from home or names that will blend in at school. Parents scroll baby-name websites looking for something that sounds unique but not strange.

The Inquiring Photographer’s question feels surprisingly modern because the stakes have not really changed. A name is still the first story the world hears about you. In 1925, on a busy New York sidewalk, people were already deciding whether that story was one they wanted to keep.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did immigrants really have their names changed at Ellis Island?

No. Historians agree that Ellis Island officials rarely changed names. Passenger lists were created in Europe, and inspectors usually copied from those documents. Most name changes happened later, in U.S. courts, workplaces, or schools, when immigrants or their children chose to simplify or anglicize their own names.

How common were legal name changes in the 1920s?

Legal name changes were not rare, especially in big cities with large immigrant populations. Court records from the 1910s and 1920s show steady numbers of petitions, often from people who wanted shorter, more “American” names. But many people simply adopted new names informally without going through the courts.

Why did so many actors in the 1920s change their names?

Film studios and theater managers preferred short, catchy, Anglo-sounding names that were easy to print and remember. Performers with long, ethnic, or hard-to-pronounce names often adopted stage names to appeal to wider audiences. This practice helped normalize the idea that a name could be part of a public persona, separate from a private identity.

Did women in the 1920s ever keep their maiden names after marriage?

Yes, but it was unusual. A small number of women, often involved in feminist or professional circles, kept their birth surnames. Activists like Crystal Eastman and groups like the Lucy Stone League argued that women should not be forced to give up their names. Most women, however, still took their husband’s surnames in both law and custom.