“It’s mind-boggling and unpredictable. We don’t really know what is in here. Every single telegram has a story behind it, from the president to the greatest generals and to the privates and telegraph operators. It’s like putting together a huge jigsaw puzzle.” – Olga Tsapina, curator of the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Civil War Documents.

15,971 telegrams were recovered in a wooden foot locker in 2012. They’d been lost for over a century. Now, finally, their voices are being heard. They tell a raw, uncensored story of the Civil War as seen through the eyes of Abraham Lincoln, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, and others. Beyond that, there’s the thoughts and plans of the regular soldier on the battlefield – of captains, colonels, privates, and everything in between. They paint an invaluable picture of the war – a play-by-play that reads whip-quick and desperate.

One telegram read: “We will not remain undisturbed tonight. Even the Rail Road men have been ordered to leave.” Others tell a story not often spoken aloud. In 1865, Ulysses S. Grant composed a telegram to the Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, saying, “I would call attention to the fact that our white troops are being paid whilst the colored troops are not. If paymaster could be ordered here immediately to commence paying them it would have a fine effect.”

The telegrams reflect the questions, concerns, and whispered, coded thoughts of the Union Army – hundreds of thousands of men trying desperately to hold together a nation on the brink of collapse. The country was falling apart at the seams.

They’re powerful because they’re raw. They’re made of every-day stuff, reminding us that the people we read about in the history books were real, with their own thoughts and concerns. Some were as lofty as battle strategies, others as mundane as ordering a barrel of whisky to keep men’s spirits up in the desolate, dark battle ahead.

A Play-by-Play Tale

The telegrams were eventually compiled into one place and kept in Thomas T. Eckert’s papers. He was a friend and confidant of President Lincoln, and head of the U.S. military telegraph office at the War Department. He kept the documents in storage, and from there, after his death, they disappeared.

They briefly flashed into view in 2008 at an auction in New York, and were sold to a rare books company. In 2012, the footlocker and papers were sold to the Huntington Library. They had been well looked after – stored in a clean, dry place. The pages were crisp, carefully kept, with barely a tear, the pages only a little yellowed.

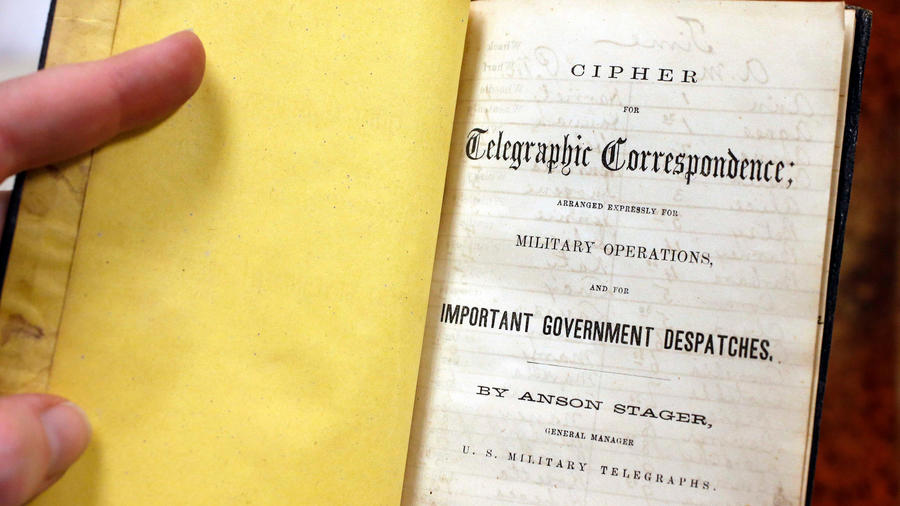

Many of the documents were written in code. Many are real-time communications between Lincoln himself and his commanders in the field. The president would spend hours pouring over the telegraphs.

500 of the telegrams in the documents were either sent by or addressed to President Lincoln himself. These won’t be displayed to the general public, as they’re not particularly gripping.

“I don’t believe they’ll be secret revelations coming out of these telegrams,” Daniel W. Stowell, director and editor of the papers of Abraham Lincoln said in an interview with the Los Angeles Times, “But the immediacy of them is a new way to see the fog of war.”

One telegram tells of a “great battle very soon”. It was sent the same day of the Battle of Gettysburg.

In June 1863, Maj. Gen. Robert Schenck sent a telegram that’s included in the group of papers detailing the formations of Robert E. Lee’s army. “Their Cavalry force at Culpepper is probably more than thrice twelve thousand. I would advise that the militia of Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Ohio be at once called out as there is doubtless a mighty raid on foot.”

Just two weeks later, the Union Army had Lee’s army surrounded. A telegram to Lincoln says, triumphantly: “If the thing is pressed I think Lee will surrender.” Lincoln responded: “Let the thing be pressed.”

History unfolded. The Union Army did, indeed, press on Lee. On April 9th, 1865, the Southern general surrendered.

Jumping forward in the telegrams to a week after the Union’s victory, the telegraph lines lost their victorious tone. They told of the President’s assassination.

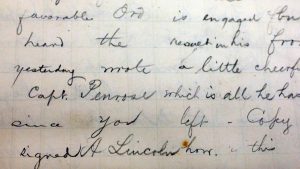

“The president continues insensible and is sinking,” Stanton wrote in one. A few hours passed the country in a nonsensical blur. At 7:22 AM, on April 15, 1865, President Lincoln was dead. “Now,” Stanton typed in a later telegram, “he belongs to the ages.”

It’s a chilling story – an amazing, unique play-by-play of the entire Civil War as told in military dispatches. Seth Kaller, a rare books dealer, remarked: “This was one of the most undervalued lot of archives that I’ve handled.”

Now, the telegrams rest in good hands at the Huntington Library. Never again will their stories be lost, their voices silent. They tell us a war story in vivid living color.