Picture a line of infantry watching a wall of horses thunder toward them. The ground shakes, the air fills with snorting and metal. Then a strange thing happens in many real battles: the horses do not simply mow men down like bowling pins. They slow, they veer, they stop short.

So what actually happened when a medieval cavalry line hit a body of men on foot? Did warhorses really trample people, or did instinct kick in and make them shy away? The answer sits at the intersection of animal behavior, training, and tactics, and it is not what Hollywood taught you.

What was a medieval cavalry charge, really?

A medieval cavalry charge was not just “horses running fast into people.” It was a coordinated attack by mounted warriors who used speed, mass, and fear to break an enemy’s formation or morale. The horse was a weapon, but also a living, thinking partner with its own limits.

In simple terms: a cavalry charge is an attempt to hit an enemy formation with enough shock that it breaks. That shock can come from physical impact, from the threat of impact, or from the psychological pressure of a wall of horses and armed riders bearing down.

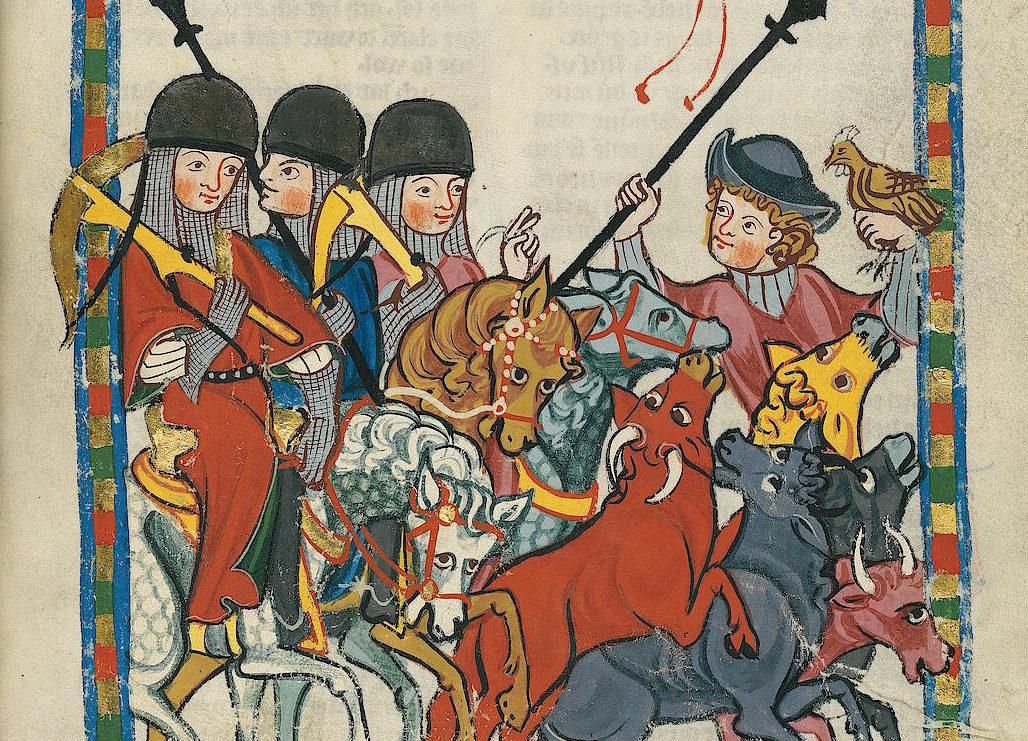

Warhorses were usually stallions or geldings, bred heavier and more muscular than ordinary riding horses. In Europe, the classic image is the destrier, though that word was more about use and status than a specific breed. In the Islamic world and Central Asia, lighter but very tough steppe and Arabian horses dominated.

These animals were trained to tolerate noise, blood, crowds, and pain. They were taught to move toward danger, not away from it. They could bite, strike with their forehooves, and kick. A single kick can kill a person. A 500-kilogram animal landing on you can crush bones.

But even the best-trained warhorse still had instincts. Prey animals avoid smashing into solid objects. So a cavalry charge was always a negotiation between human intent and equine self-preservation. That tension shaped how battles were actually fought, which is why understanding it changes how we read medieval warfare.

What set it off: instinct vs training in warhorses

The Reddit question gets to the heart of it: a horse’s instinct is to avoid obstacles, not plow through them. That is true. Left to its own devices, a horse will not happily run chest-first into a solid wall of bodies and spears.

Horses are prey animals with strong flight responses. Their eyes are set to the side, giving them a wide field of vision. They are very good at spotting threats and avoiding collisions. Anyone who has ridden a nervous horse past a plastic bag knows how quickly they can shy away from something unfamiliar.

Warhorse training, from antiquity through the Middle Ages, tried to override part of that response. Manuals from later periods, like the early modern riding schools, describe desensitizing horses to drums, gunfire, flags, and close-packed formations. Earlier, the process would have been less formal but similar in spirit: expose the horse to chaos until it stops panicking.

Riders also trained specific combat behaviors. Horses could be taught to shoulder into people, to step on fallen enemies, to strike out with their forelegs. There are medieval references to horses biting in battle. None of this means the horse wanted to “kill.” It means the animal had learned that moving into human bodies, even aggressively, was allowed and rewarded.

Yet there was a hard limit. You can condition a horse to run at a line of men who look like they might move. You cannot easily convince it to ram full speed into what it perceives as a solid, immovable barrier bristling with sharp things. That is why disciplined infantry with spears or pikes were so dangerous to cavalry. The horses themselves often refused to complete the impact.

This balance between instinct and training meant cavalry were terrifying against scattered or wavering troops, but far less effective against tight, confident formations. That difference shaped who won and lost battles.

The turning point: what actually happened at impact?

So when horse met human, what did it look like?

In many medieval and early modern battles, the decisive moment came before physical contact. If infantry wavered, opened gaps, or ran, the cavalry did not have to smash into a solid wall. They chased, cut down fugitives, and rode through broken ranks. That is when trampling and crushing happened most often: when people were already falling, not standing firm.

When infantry held, the story changed. Accounts from the Hundred Years’ War, for example, show French cavalry failing to break English defensive lines at battles like Crécy (1346) and Poitiers (1356). Arrows, terrain, and dismounted men-at-arms all played a role, but so did the simple fact that horses would not throw themselves onto a dense hedge of spears and men.

Later, in the age of pikes and muskets, we have even clearer evidence. At battles like Waterloo (1815), British infantry formed squares against French cavalry. Contemporary descriptions repeatedly mention horses coming up to the bayonets and veering away. Riders could not force their mounts to impale themselves. The same basic dynamic would have applied in earlier centuries with spear walls.

That does not mean no one was trampled. Fallen soldiers in front of a formation, wounded men crawling away, or individuals who broke ranks could absolutely be run over. A charging horse can knock a person flat, break ribs, crush limbs. But the idea of horses casually bowling through a tight, braced line of healthy adults is not supported by what we know of equine behavior or battlefield accounts.

So the “impact” of a cavalry charge was often more psychological and positional than purely kinetic. It was about making the other side blink first. That reality explains why morale and discipline mattered so much in premodern warfare.

Who drove it: riders, horses, and the tactics they used

The key figures in this story are not just famous kings and generals. They are the mounted elites who invested years in training themselves and their horses, and the commanders who learned when cavalry could be decisive and when it would die on a hedge of spears.

In Western Europe, the knight was the classic heavy cavalryman. From roughly the 11th to 14th centuries, mounted shock combat was central to aristocratic identity. Knights trained from youth to control their horses with legs and seat, leaving their hands free for lance and sword. They practiced charging in formation, wheeling, and rallying.

Yet even they did not simply expect their mounts to act like mindless battering rams. Chronicles describe knights circling, probing for weak points, and dismounting when conditions were bad for horses. At the Battle of Courtrai in 1302, French knights charged Flemish infantry in marshy ground and were cut down. The problem was not just the men on foot. It was that the terrain and the tight pike formations turned the horses’ advantages into liabilities.

Elsewhere, cavalry tactics varied. Steppe nomads like the Mongols relied on light, fast horses and missile fire. They rarely tried to crash into solid infantry. Instead they showered enemies with arrows, feigned retreats, and attacked flanks and stragglers. Their horses were deadly in a different way: as platforms for mobile archery and pursuit.

In the Islamic world and Byzantium, medium and heavy cavalry mixed shock and missile tactics. Again, the goal was usually to create or exploit disorder, not to commit suicide against a braced wall of spears.

All these riders understood, consciously or not, what their horses would and would not do. Their tactics grew from the physical and mental limits of the animals. That human-animal partnership, with its constraints, shaped the entire character of medieval warfare.

What it changed: infantry, armor, and the myth of the invincible charge

Once you accept that horses will not happily run into a solid obstacle, a lot of medieval military history looks different.

First, it explains why infantry never disappeared. Even in periods when knights dominated the social order, foot soldiers with spears, good morale, and some protection could blunt cavalry. The Battle of Legnano (1176), where Lombard infantry held against the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa’s cavalry, is one example among many where men on foot stopped mounted elites.

Second, it clarifies why certain weapons spread. Long spears, pikes, and later halberds and bills made infantry formations look and feel more like solid hedges to a charging horse. A single spear might be dodged. A forest of spearpoints, held by steady men, looked like death. Horses reacted accordingly.

Third, it reframes armor. Heavy armor for cavalry was not just about surviving a direct hit. It was also about letting riders get close enough to threaten infantry without being shot out of the saddle. If you could ride up to within a few meters of a line and make them flinch, you might never need the horse to actually crash into them. The armor bought you that approach.

Finally, it punctures a popular myth: that medieval battles were decided by unstoppable knightly charges flattening peasants. Sometimes cavalry did roll over poorly trained or already frightened infantry. More often, their success depended on timing, terrain, and the enemy’s nerve. The limits of the horse’s body and brain kept pure shock action from being a magic win button.

Seeing those limits helps explain the long, messy contest between mounted and foot forces that shaped medieval politics and warfare.

Why it still matters: horses, myths, and how we picture the past

So, would cavalry horses kill people by running over them? Yes, they could and did trample, kick, and crush individuals, especially once formations broke or men fell. No, they were not four-legged bulldozers happily smashing into dense, braced lines of armed humans.

The horse’s instinct to avoid solid obstacles remained strong, even in trained warhorses. Training could push them to move into crowds, to accept chaos, and to use their bodies aggressively. It could not easily make them commit suicide on a wall of spears. That limit shaped tactics, weapon design, and the balance between cavalry and infantry for centuries.

This matters because our mental picture of medieval warfare is often wrong. Films and games love the image of cavalry mowing down ranks like wheat. That image erases the skill of infantry who held their ground, the tactical judgment of commanders who knew when not to charge, and the animal reality of the horses themselves.

Understanding what horses would and would not do gives us a more human, and more honest, view of the Middle Ages. It reminds us that even in war, people fought within the constraints of muscle, bone, fear, and training, not in the physics-free world of legend.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a horse really kill a person in battle?

Yes. A horse can kill a person with a kick, a strike from its forehooves, or by trampling and crushing someone on the ground. In battle, many injuries came from people being knocked down and then stepped on or ridden over during pursuit or chaos, rather than from horses smashing into tight, standing formations.

Did medieval warhorses actually run into infantry lines?

Trained warhorses would charge toward infantry and could move into loose or wavering groups, but they usually avoided ramming full speed into dense, braced lines of spears or pikes. Their prey-animal instincts made them shy away from what they perceived as solid, dangerous obstacles. Cavalry relied more on fear, speed, and exploiting gaps than on pure collision.

Could you train a horse to ignore its instinct and trample people?

You could train a horse to tolerate crowds, noise, and violence, and to use its body aggressively by biting or striking. You could not easily train it to commit suicide by running chest-first into a solid wall of armed men. Training expanded what the horse would accept, but it did not erase basic self-preservation instincts.

Why were medieval cavalry charges so feared if horses avoided solid obstacles?

Cavalry charges were feared because of their speed, noise, and the social status of the riders. The psychological shock often made infantry panic or break before impact. Once a formation wavered or ran, cavalry could ride through, cut down fugitives, and trample the fallen. The threat of being run down was real, even if horses rarely smashed into perfectly solid lines.