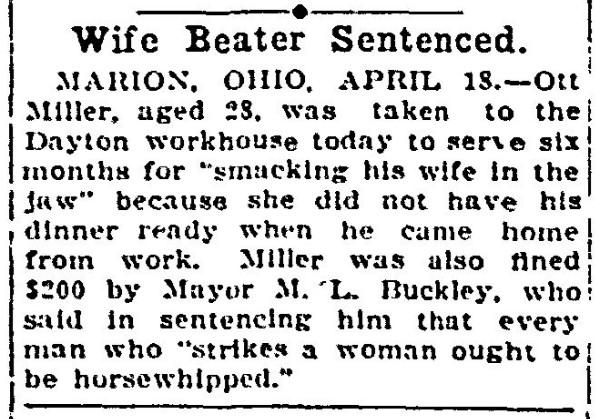

Picture a cramped police court in April 1925. A man in a work shirt, jaw clenched. A woman with a bruised cheek, eyes fixed on the floor. The newspaper the next morning sums it up in three blunt words: “Wife Beater Sentenced.”

That kind of headline popped up all over American and British papers in the 1920s. It looks simple: violent husband, quick justice. But it hid a messy world of domestic violence, weak laws, and women trying to bend the system to protect themselves.

Domestic violence in the 1920s was common, rarely prosecuted, and wrapped in shame. When a paper bothered to print “Wife Beater Sentenced,” it usually meant something unusual had happened. Either the case was unusually brutal, the sentence was unusually harsh, or a judge was trying to make an example.

Here are five things that headline from April 19, 1925 really points to: what counted as “wife beating,” how the law treated it, what options women actually had, and why these short, sharp stories mattered in the long run.

1. “Wife beating” was a legal category, not just an insult

When a 1920s paper wrote “wife beater,” it was not just name-calling. In many places it described a specific offense in law or at least a familiar category in police and court records: assault on a wife by her husband.

By the late 19th century, most U.S. states and many European countries had formally outlawed a husband’s right to physically “correct” his wife. Courts had once tolerated a certain level of violence as a private matter. By the 1920s, on paper, that right was gone.

For example, in North Carolina, the state supreme court had long been quoted for saying that a husband could whip his wife with a switch no thicker than his thumb. By the early 1900s that old rule was being rejected, and judges were more willing to call such behavior criminal assault. In Britain, the 1895 case R v. Jackson had already made it clear that husbands could not imprison or physically control their wives as property.

Yet the phrase “wife beating” stayed in use. It showed up in police blotters, reform campaigns, and headlines. In some American cities, like Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, municipal courts kept informal tallies of “wife beaters” brought in for short jail terms or fines.

So when a 1925 headline reads “Wife Beater Sentenced,” it is not just describing a man who happened to hit his wife. It is signaling a recognized social type, the “wife beater,” that reformers, judges, and journalists were already talking about as a problem.

That matters because it shows society was beginning to name domestic violence as a distinct wrong, not just a private quarrel, which is the first step toward treating it as a public crime.

2. Sentences were usually light, even when headlines sounded tough

The word “sentenced” in a 1925 headline sounds heavy. In reality, most “wife beater” sentences were short, symbolic, or conditional. The law treated domestic violence as a nuisance more often than as a serious felony.

Typical punishments in the 1920s included small fines, a few days to a few months in a city jail, or suspended sentences on the condition that the man “behave” or support his family. Judges often warned men in open court but then let them go home.

For a concrete example, take the way some American cities used the “workhouse.” In Cleveland and other industrial towns, a convicted wife beater might get 30 days in the workhouse, doing hard labor. Newspapers would print the sentence as a warning. Yet many first-time offenders walked out with a suspended term if their wives pleaded for financial support instead of jail.

Even the rare “harsh” sentences were modest by modern standards. In 1911, a New Jersey judge sentenced a man named John C. Flaherty to six months in jail for beating his wife, and it made national news because it was considered unusually severe. In the 1920s, similar cases still drew attention precisely because they were not the norm.

So that April 19, 1925 headline probably masked a fairly mild outcome. A few weeks in jail, a fine, or a warning. The drama was in the words, not always in the punishment.

That matters because it reminds us that press coverage could give an impression of tough justice while the legal system continued to treat domestic violence as a low-level offense.

3. Women’s options were narrow, and the law often pushed them to stay

The woman behind the headline had very few good choices. Reporting her husband could mean losing his wages, facing retaliation at home, or public shame in court. Divorce was expensive, slow, and socially risky.

In the 1920s, divorce rates were rising, but a woman still needed specific grounds, like “extreme cruelty,” and had to prove them. In many U.S. states and in Britain, judges were reluctant to grant divorces, especially to working-class women who might end up in poverty.

A concrete case: in New York City’s Domestic Relations Court, created in 1919, judges often urged “reconciliation.” A wife might come in with bruises and ask for protection. The judge could order the husband to pay support, maybe issue a suspended sentence, then tell the couple to try again. Social workers attached to the court would visit homes and report back, but they too tended to push for keeping the family together.

Charity organizations and settlement houses heard countless stories of “wife beating” but had limited tools. They could help a woman find temporary shelter, sometimes in a church-run home, or help her file a complaint. Long-term safety was another matter. Police might refuse to intervene in “family disputes” unless the violence was extreme.

So when a woman in 1925 went far enough to get a “wife beater sentenced” headline, she had probably already endured a lot. She might have been pushed into court by neighbors, a priest, or a social worker. She might have hoped that a brief sentence would scare her husband straight, not end the marriage.

That matters because it shows that the legal system was not built to free women from violent homes. It was built to discipline men just enough to keep families intact.

4. Public shaming was part of the punishment, by design

Those blunt headlines were not just reporting. They were a form of public shaming. Judges, reformers, and editors knew that having your name printed under “Wife Beater” could hurt your reputation, job prospects, and standing in your community.

Some officials leaned into that. In the early 1900s, a few American cities experimented with “wife beater’s courts” or special dockets where all such cases were heard together. The idea was that men would be embarrassed in front of other men. In some places, like Maryland and Delaware, there were even short-lived laws allowing whipping as a punishment for convicted wife beaters, and those whippings drew crowds and headlines.

By the 1920s, whipping was rare and controversial, but the logic of public shame remained. Newspapers printed names, addresses, and sometimes employers. A 1923 Chicago report on domestic cases noted that some men begged the judge not to publish their names, fearing they would be fired.

Reformers in groups like the National Conference of Social Work debated this tactic. Some argued that public exposure was the only thing some men feared. Others worried that it punished families twice, by making it harder for the man to earn a living.

In Britain, local papers did the same. A short item might read: “John Smith, 35, laborer, of High Street, was fined 40 shillings for beating his wife.” No commentary, just facts that everyone in town could read.

So that 1925 “Wife Beater Sentenced” line was not just a neutral label. It was meant to sting, to mark the offender as a certain kind of man in the eyes of neighbors and employers.

That matters because it shows how early responses to domestic violence relied on shame and reputation, not just on formal prison time, to try to change behavior.

5. These cases fed into early debates about gender, alcohol, and reform

Every “wife beater sentenced” case slotted into bigger arguments of the 1920s about what kind of behavior the state should police. Domestic violence sat at the crossroads of debates over alcohol, masculinity, and women’s new political power.

Alcohol was the most common excuse and explanation. During Prohibition in the United States (1920–1933), temperance activists claimed that banning liquor would reduce wife beating. Court records do show many cases where men were described as drunk when they attacked their wives. Judges often lectured offenders about drink. A 1920s headline might even read “Drunken Wife Beater Sentenced,” tying the two together.

Women’s suffrage also mattered. American women gained the vote in 1920, British women over 30 in 1918 and over 21 in 1928. Suffrage leaders had long used stories of wife beating to argue that women needed political power to protect themselves and their children. After they got the vote, some pushed for stronger family courts, better police training, and more shelters.

For example, in New York, women reformers helped shape the Domestic Relations Court, which opened in 1919. They wanted a place where family violence and non-support could be handled more seriously than in ordinary police courts. The court was imperfect, but it marked a shift toward treating domestic issues as a public concern.

At the same time, there were anxieties about masculinity after World War I. Millions of men had returned from the trenches. Some came back with trauma that no one had language for. Others struggled to find work. Newspapers sometimes framed wife beating as a symptom of “degenerate” or “unmanly” behavior, a way to talk about male failure without talking about war or unemployment directly.

So a small 1925 item about a wife beater being sentenced was not isolated. It plugged into arguments about whether the state should step into the home, whether alcohol laws worked, and what kind of authority husbands should have.

That matters because it shows how domestic violence cases, even when treated as routine, helped push societies to rethink gender roles and the boundary between private life and public law.

Why a three-word headline from 1925 still matters

“Wife Beater Sentenced” looks simple on the page. Behind it were a frightened woman, a man on a bench, a judge juggling law and custom, and a society only starting to admit that violence at home was not just a private matter.

Those 1920s cases did not end domestic violence. Sentences were often light. Many women stayed silent. But the very fact that newspapers named “wife beaters,” that courts tracked them, and that reformers argued about them, helped move the issue from the shadows into public view.

Modern debates about restraining orders, mandatory arrest policies, and survivors’ rights all grow out of that long, uneven history. When we read a 1925 headline about a wife beater being sentenced, we are looking at an early, imperfect stage of a fight that is still going on: the struggle to treat violence inside the home as seriously as violence on the street.

Frequently Asked Questions

What did “wife beater” mean in the 1920s?

In the 1920s, “wife beater” was a common term for a husband who assaulted his wife. It was used in police records and newspapers to describe men charged with domestic assault, not just as a casual insult.

Were wife beaters really punished harshly in the 1920s?

Usually no. Despite tough-sounding headlines, most convicted wife beaters received small fines, short jail terms, or suspended sentences. Serious prison time was rare and tended to make news because it was unusual.

Could women in the 1920s get protection from abusive husbands?

Their options were limited. Women could file complaints and seek support orders, and some cities had special domestic relations courts. But police often avoided “family disputes,” divorce was hard to obtain, and many women were pressured to reconcile.

How did alcohol and Prohibition affect domestic violence cases?

Alcohol was frequently mentioned in domestic violence cases, and temperance activists argued that drink caused wife beating. During Prohibition in the U.S., reformers claimed banning liquor would reduce abuse, but court records show that violence in the home did not disappear.