Picture two Greeks, both from the same peninsula, separated by only a few centuries.

The first is a Mycenaean warrior around 1300 BCE. He wears a tight, patterned kilt, a fitted, colorful tunic, maybe a boar’s tusk helmet. His hair is long and carefully styled. Frescoes show bare chests, bright dyes, and complex patterns that look more at home in a palace than a battlefield.

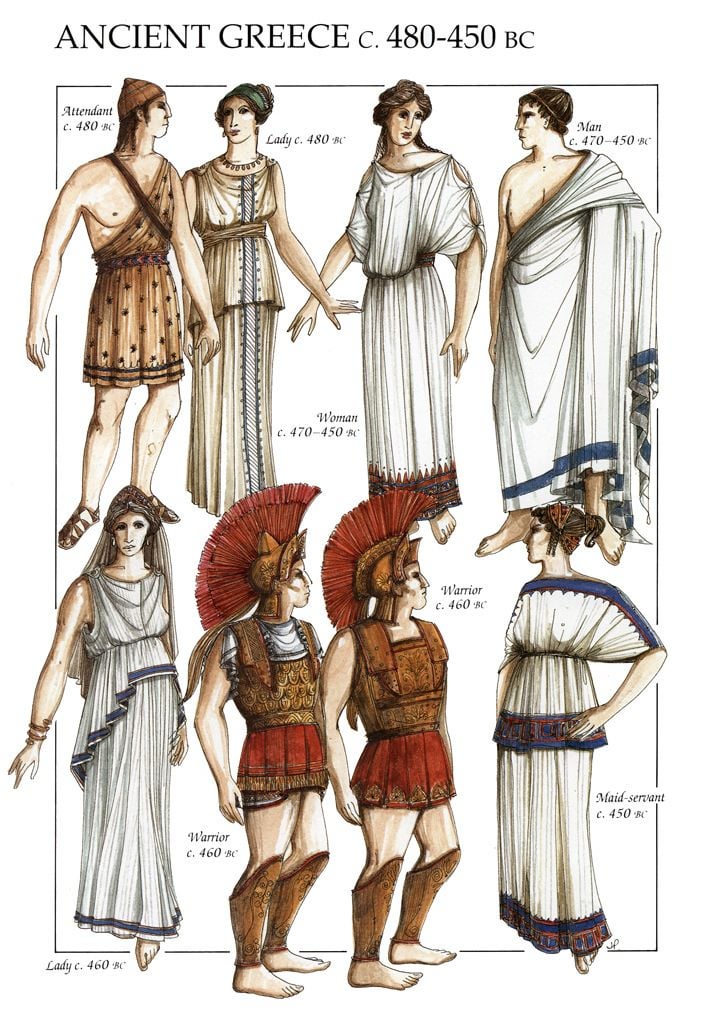

The second is an Athenian citizen around 450 BCE. He wears a plain woolen himation, basically a big rectangle of cloth draped around the body. Under it, a simple tunic. His hair is short. His beard is full. The colors are muted. No flashy patterns, no tight tailoring.

These are both “Greek,” yet they look like people from different worlds. Something happened between the fall of the Mycenaean palaces around 1200 BCE and the rise of classical Greece. Greek clothing went from fitted, colorful, and palace-luxurious to simple, draped, and almost austere.

So what forced this radical change? The short answer: the Bronze Age collapse wrecked the old palace economy, cut off trade in luxury goods, and helped create a new social and political order that preferred simplicity over display.

What was Greek clothing before and after the Bronze Age collapse?

First, a clean definition. The “Bronze Age collapse” in the eastern Mediterranean was a period around 1200–1100 BCE when several palace-based states, including Mycenaean Greece, disintegrated. Before that collapse, Mycenaean elites wore tailored, colorful garments. After it, Greeks in the so-called Dark Age and Archaic period shifted to simpler, draped clothing.

Mycenaean clothing, as we know it from frescoes, figurines, and Linear B tablets, was surprisingly elaborate. Men could wear short, tight kilts, patterned tunics, and sometimes long robes. Women wore layered skirts with flounces, fitted bodices, and exposed breasts in some Minoan-influenced art. Both sexes are shown with bright colors and complex designs. This was fashion tied to palace culture, imported dyes, and specialized textile workshops.

By contrast, the classical Greek wardrobe was built around a few basic, unsewn rectangles of cloth:

• Chiton: a tunic made from a rectangle of linen or wool, pinned or sewn at the shoulders.

• Himation: a larger woolen cloak or mantle, draped over the chiton or bare body.

• Peplos (for women): a large rectangle of wool, folded and pinned at the shoulders, belted at the waist.

These garments were not tailored in the Mycenaean sense. They were draped and pinned. Decoration existed, but the overall look was much simpler. Classical art, especially from the 5th century BCE, tends to show solid colors or modest borders, not the busy patterns of Bronze Age frescoes.

So the basic story is: Mycenaean Greece had palace-supported, highly crafted, colorful clothing. Post-collapse Greece moved toward simpler, draped garments that used less tailoring and, often, less ostentatious decoration. That visual shift marks a deeper change in how Greek society was organized.

What set off the change in Greek clothing after the Bronze Age?

The root cause was not a fashion trend. It was the collapse of the entire economic and political system that had supported Mycenaean luxury textiles.

Between roughly 1200 and 1100 BCE, the major Mycenaean palace centers like Mycenae, Pylos, and Tiryns were destroyed or abandoned. Archaeologists still argue over the exact mix of causes: earthquakes, internal revolts, drought, invasions, or all of the above. Whatever the trigger, the result is clear. The palace system that had dominated Greece in the Late Bronze Age vanished.

Those palaces were not just royal residences. They were economic engines. Linear B tablets from Pylos and Knossos record large-scale textile production: flocks managed by the palace, wool quotas, teams of weavers, and distribution of finished cloth as rations or gifts. The palace controlled access to fine wool, imported dyes, and skilled artisans.

The Bronze Age collapse disrupted long-distance trade networks that brought in luxury items and materials. Indigo, murex purple, tin for bronze, and possibly certain fine linens were all tied to those routes. When those networks frayed, the supply of high-status, high-labor textiles shrank.

Without palaces organizing and financing specialized workshops, textile production shifted back toward smaller, household-based work. People still spun and wove, but the scale and specialization dropped. Simpler garments, made from rectangles of cloth woven on household looms, fit that new reality better than tailored, multi-piece outfits.

So the first big answer to “what forced the Greeks to change their clothing?” is economic. The destruction of the Mycenaean palaces and their trade networks removed the infrastructure that had made elaborate, colorful clothing common among elites.

What was the turning point from Mycenaean style to classical simplicity?

There is no single year when Greeks woke up and decided to grow beards and wear plain chitons. The change unfolded over several centuries, from the so-called Dark Age (c. 1100–800 BCE) into the Archaic period (c. 800–500 BCE).

In the immediate post-collapse centuries, archaeological evidence suggests a drop in complexity across the board. Settlements shrank. Writing disappeared. Burials became simpler. That likely applied to clothing too, though textiles rarely survive. We see fewer depictions of highly patterned garments. Jewelry and metal accessories also become rarer.

By the 8th and 7th centuries BCE, Greek communities were recovering and growing again. This is the era of Homeric poetry, the rise of the polis, and renewed trade with the Near East. Art from this period, like geometric pottery and early sculpture, shows people wearing simple tunics and cloaks, not the tight, patterned outfits of Mycenaean frescoes.

At the same time, Greeks were in contact with the Near East and Egypt, and some clothing ideas flowed in. The Ionian chiton, a lighter linen tunic, probably had eastern inspirations. Yet the basic Greek solution remained the same: large rectangles of cloth, draped and pinned, not cut and stitched into complex shapes.

Hair and beards also changed. Mycenaean men are often shown clean-shaven with long hair. By the Archaic period, the Greek ideal for a free male citizen was a short-haired, bearded man. That shift is cultural, not simply economic. Beards became markers of adult male status, while long hair in some city-states was reserved for youths or particular elites, or later associated with “barbarians.”

By the time we reach classical Athens in the 5th century BCE, the look is fixed in our imagination: simple draped garments, short hair, beards, and relatively restrained use of color and pattern. The turning point was not a single fashion revolution, but the slow solidification of new norms in a world no longer run by palace kings.

So the turning point was the long Dark Age and early Archaic recovery, when Greek communities rebuilt without palaces and settled into new, simpler clothing habits that matched their new political and social structures.

Who drove the change: elites, households, or ideology?

Fashion is never just about what is technically possible. It is about what people want to signal. In post-Mycenaean Greece, the people who mattered most in setting those signals were no longer palace kings, but citizen elites in emerging city-states.

In the Bronze Age, kings and their courts used elaborate clothing to display hierarchy. The palace controlled the best textiles, so wearing them showed your place in that system. After the collapse, power shifted to smaller-scale local leaders, then to aristocracies, and in some places to broader groups of citizens.

By the Archaic and Classical periods, Greek elites had a new ideal: moderation. The word was sophrosyne, a mix of self-control, restraint, and balance. In that moral universe, dressing in wildly ornate, body-hugging outfits could look suspiciously like luxury, softness, or even Eastern decadence.

Philosophers and moralists did not invent the chiton, but they helped give simple clothing a positive spin. Later writers like Xenophon and Plato praise modest dress and criticize excessive adornment. Herodotus, writing about Persians in rich trousers and long robes, uses their clothing as a shorthand for their difference from Greeks.

Households drove the practical side. Most Greek clothing was made at home by women using vertical looms. Rectangular pieces of cloth were easier to produce and adapt. You could use the same basic loom width for a chiton, a himation, or a peplos. Cutting and sewing wasted precious fabric. Draping conserved it.

So the drivers were mixed: economic limits, domestic production, and a new ideology that saw virtue in simplicity. Greek elites chose to embrace and codify a style that matched their political values and social realities, instead of trying to resurrect the ostentatious palace fashions of their Mycenaean ancestors.

So the change was driven by a new class of citizen elites and household producers who turned practical constraints into a moral and cultural ideal of simple, draped clothing.

What did this change in clothing actually do to Greek society?

Clothing is not just decoration. It shapes how people move, how they see each other, and how they mark identity. The shift from Mycenaean fashion to classical Greek dress had several concrete consequences.

1. A more uniform look among male citizens

The classical Greek male wardrobe was relatively standardized. A citizen in Athens, Corinth, or Thebes might all wear some version of chiton and himation. Status could still show in fabric quality, color, and jewelry, but the basic silhouette was shared. That visual uniformity fit a world where free male citizens claimed to be political equals, even if wealth and power differed.

2. Clearer visual markers of gender and status

Women’s clothing remained more conservative and enclosed, especially in classical Athens. The peplos and later the Ionic chiton covered the body more fully. Combined with veils in some contexts, this created a stronger visual divide between male and female appearance than we can easily see in Mycenaean art.

Slaves and foreigners could be marked by different styles, fabrics, or the presence of trousers, which Greeks associated with non-Greek peoples like Persians and Scythians. Clothing helped draw the line between “Greek citizen” and “everyone else.”

3. A new aesthetic of the body

Mycenaean art often clothes the body in patterned, fitted garments. Classical Greek art, especially sculpture, uses drapery to reveal the body’s form. The simple chiton and himation became tools for artists to suggest muscles and movement beneath cloth. The ideal male body, often shown nude in art, was framed by simple garments in daily life.

That aesthetic fed into Greek ideas about athletics, warfare, and beauty. The same society that dressed its citizens in plain drapery also celebrated nude athletes and heroic warriors. The contrast with the richly clothed, trouser-wearing Persians in Greek art is not accidental.

4. Memory and distance from the Mycenaean past

By the classical period, Greeks had myths about Mycenaean heroes like Agamemnon, but they did not dress like them. The visual gap between Bronze Age and classical clothing helped turn the Mycenaean era into a semi-mythic age, grand but distant.

So the clothing change did not just reflect new realities. It helped create a shared citizen identity, sharpen gender and status lines, and reinforce Greek ideas about their own bodies and their distance from both their ancestors and their eastern neighbors.

Why does this shift in Greek clothing still matter today?

The question that sparked this whole discussion is a modern one: why did Greeks go from colorful, flamboyant Mycenaean outfits to simple, bearded classical looks and never really go back?

The answer matters for a few reasons.

First, it reminds us that “Greek” is not a single, timeless style. The toga-clad, bearded philosopher in a plain garment is a product of a specific historical moment, not an eternal Greek essence. Earlier Greeks dressed very differently, and later Greeks under Hellenistic and Roman rule changed again.

Second, it shows how fashion can be driven by collapse as much as by creativity. The Bronze Age collapse forced Greeks into a world with fewer resources, less centralized production, and new political forms. Their clothing adapted. What began as necessity became virtue. Simplicity, drapery, and beards turned into symbols of moral seriousness and civic identity.

Third, it helps explain why our own mental picture of “ancient Greece” is so narrow. Classical art survived better than Bronze Age frescoes. Marble statues lost their paint. The result is a modern myth of white, simple-clothed Greece. When we compare that to the colorful Mycenaean past, we see how much of our image is shaped by what survived, and by one particular era’s choices.

Finally, the story connects fashion to power. When the palace system died, its clothing died with it. When citizen elites rose, they chose a style that fit their values. Every time we see a statue of a draped Athenian or a vase painting of a bearded hoplite, we are looking at the long shadow of a collapse that forced Greeks to rethink not just their politics and economy, but what they wore on their backs.

So the shift from flamboyant Mycenaean dress to simple classical drapery matters because it is a visible thread that runs from the Bronze Age collapse straight into the way we still imagine ancient Greece today.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why did ancient Greek clothing become simpler after the Bronze Age?

Greek clothing became simpler after the Bronze Age because the Mycenaean palace system collapsed around 1200–1100 BCE. Those palaces had organized large-scale textile production and long-distance trade in luxury materials. When they fell, textile production shifted to households, trade networks shrank, and elites in the new city-states embraced a style of simple, draped garments that matched their more modest economic and political realities.

Did the Bronze Age collapse directly change how Greeks dressed?

Yes, indirectly. The Bronze Age collapse destroyed the palace economies that supported elaborate, colorful clothing and cut off many trade routes for fine dyes and fabrics. Without centralized workshops and easy access to luxury materials, clothing production became smaller-scale and more practical. Over the following centuries, Greeks adopted simple rectangular garments like the chiton and himation, which were easier to weave at home and fit the new social order.

Why did classical Greek men wear beards but Mycenaean men often did not?

Mycenaean art often shows clean-shaven men with long hair, reflecting Bronze Age courtly styles. In the Archaic and Classical periods, Greek culture developed a new ideal in which a full beard signaled adult male status and self-control. Short hair with a beard became the norm for free male citizens, while long hair or being clean-shaven could mark youth, certain elites, or foreigners. This change is cultural and ideological rather than purely economic.

Were classical Greek clothes really all white and plain?

No. Classical Greek clothing could be dyed and decorated, and some garments had colored borders or patterns. However, compared to the highly patterned and tailored clothing of the Mycenaean period, classical garments were simpler in cut and often more restrained in decoration. Modern misconceptions come from weathered marble statues that have lost their paint and from the survival of more classical art than Bronze Age frescoes.