In the summer of 1241, near the village of Mohi in Hungary, European knights watched their enemies ride away and thought they were winning.

The Mongols had crossed the Sajó River, loosed clouds of arrows, then seemed to break. The Hungarian cavalry spurred forward in pursuit. That is when the trap closed. Fresh Mongol units appeared on the flanks, more horse archers poured arrows into the packed knights, and the Hungarian army disintegrated. King Béla IV barely escaped.

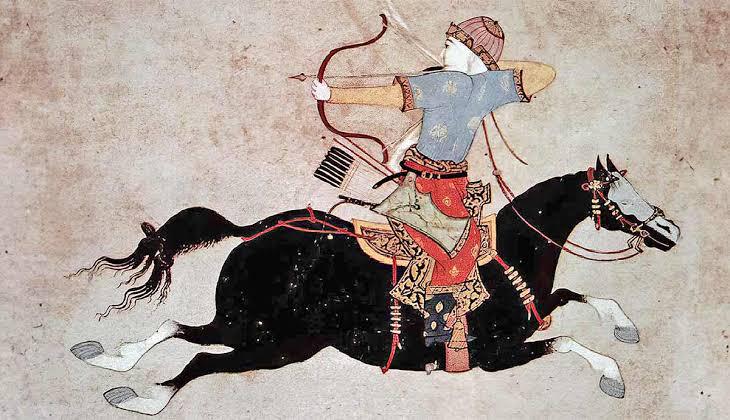

Scenes like Mohi explain the reputation of mounted horse archers. From the Scythians and Parthians to the Huns, Turks, and Mongols, steppe armies terrified settled states. A mounted horse archer was a fast-moving missile platform: hard to catch, hard to kill, and deadly at range.

Mounted horse archers were feared because they combined mobility, range, and endurance in a way most premodern armies could not match. They could choose when to fight, where to fight, and when to vanish. That is a simple, snippet-ready definition of their power.

So here is the counterfactual: what if the major medieval powers had really copied them? Not just hiring a few nomad mercenaries, but reshaping their armies around mounted archery the way the steppe peoples did.

Three scenarios make sense to test. A Latin Christian Europe that turns into a horse archer culture. A Byzantine Empire that doubles down on its own mounted archers. And an Islamic world that leans even harder into Turkic steppe warfare. Each runs into hard limits of land, money, and politics. Each would have changed the story of medieval warfare in different ways.

Why were mounted horse archers so feared in real history?

Before twisting history, you need the baseline. What did mounted horse archers actually do that made people write panicked chronicles about them?

The classic steppe horse archer was a light rider on a small, hardy horse, armed with a powerful composite bow. He carried several quivers, often a sabre or lance, and sometimes a lasso. He usually had multiple remounts. A Mongol warrior might have three to five horses. That meant he could ride far, rest mounts in rotation, and still fight effectively.

Horse archers were feared because they could attack without being caught. They fired from outside the effective range of most infantry weapons. If heavy cavalry charged, they could retreat, shoot while withdrawing, and draw the enemy into bad ground or an ambush. Ancient writers called this the “Parthian shot”. Medieval observers watching Turks or Mongols saw the same trick.

They were also a system, not just a troop type. Steppe societies bred huge numbers of horses, trained boys to ride and shoot from childhood, and organized armies around tumens and tribal units that could live off the land. Logistics and culture did as much work as the bow.

That system had limits. True steppe-style horse archer armies needed vast grazing lands, a population raised in the saddle, and a political structure that could mobilize nomad clans. They were less effective in deep forests, mountains, or swampy terrain. They struggled with long sieges without allied engineers or subject peoples.

So the question is not “why did not everyone just copy them?” The question is: under what realistic conditions could settled states have moved closer to that model, and what would that have done to medieval history?

Getting the real strengths and weaknesses of horse archers straight matters, because it sets the limits for any believable what-if scenario.

Scenario 1: What if Latin Europe became a horse archer culture?

Imagine a different 11th and 12th century Europe. Instead of doubling down on the mail-clad knight with a couched lance, Western rulers decide that the future belongs to mounted archers, and they act like it.

There is a small seed of reality here. The Normans used mounted archers at Hastings in 1066, though not in steppe fashion. The Spanish and Portuguese fought alongside light cavalry in the Reconquista. Crossbow-armed mounted troops appear in sources. But Latin Europe never turned into a horse archer civilization.

For this to change, you need a shock and a model. The shock could be the 1090s and 1100s, when Western knights in the First Crusade met Turkish horse archers in Anatolia and Syria. At Dorylaeum in 1097, the Seljuk Turks nearly destroyed the crusader vanguard with mounted archery and feigned retreats. Chroniclers noticed how vulnerable dense knightly charges were to hit-and-run tactics.

In our scenario, those lessons are taken far more seriously. Instead of treating Turks as exotic enemies, some crusader leaders decide to copy them. They recruit Turkic mercenaries, Armenian and Syrian horse archers, and bring them back to Europe in large numbers. A few ambitious kings, say in France or the Holy Roman Empire, start funding horse breeding programs and archery training for their own vassals.

The obstacles are huge. Western Europe has far less open steppe than Central Asia. Much of it is forested or heavily cultivated. Peasant agriculture and manorialism leave little room for the massive pastures needed to sustain steppe-level horse herds. A Mongol-style warrior with three to five horses is economically unrealistic for most European lords.

There is also culture and class. The knight is not just a weapon system. He is a social order. His identity is tied to heavy armor, the lance charge, and close combat. Asking him to become a light horse archer is like asking a medieval bishop to take up carpentry. It cuts against status and ideology.

So a Latin horse archer revolution would probably look like a hybrid. You might see more emphasis on lighter cavalry with bows or crossbows, more mounted sergeants trained to skirmish, and some aristocrats who pride themselves on archery skill. Think of something closer to the later Hungarian or Polish light cavalry, but on a wider scale.

On the battlefield, that could change a few things. The classic clash between French knights and English longbowmen in the Hundred Years’ War might look different if both sides had large numbers of mobile missile troops. French armies that historically charged into arrow storms at Crécy (1346) and Agincourt (1415) might instead try to screen with their own mounted archers, trading arrows and probing flanks rather than committing to suicidal frontal charges.

Strategically, more horse archers would make raiding and chevauchées even more common. The Hundred Years’ War already featured mounted raids burning crops and villages. With faster, more lightly equipped horse archers, those raids would be harder to intercept and more destructive. Rural France, already hammered, might suffer depopulation on an even larger scale.

Yet Europe would still not become a true steppe power. The density of castles, hedges, woods, and walled towns would limit the full expression of horse archer warfare. You would get more skirmishing cavalry and more fluid tactics, but not Mongol-style operational art sweeping across entire kingdoms in a single campaign season.

So what? A Latin Europe that embraced mounted archery would likely see fewer catastrophic knightly defeats by infantry and more prolonged, mobile wars of attrition, but geography and social structure would still keep it from turning into a second Eurasian steppe.

Scenario 2: What if Byzantium doubled down on mounted archers?

If any medieval state was well placed to go “full horse archer,” it was the Byzantine Empire.

Byzantium already used mounted archers. From at least the 6th century, imperial armies fielded cavalry units trained to shoot from horseback, influenced by Huns, Avars, and later steppe peoples. Manuals like the 10th century “Taktika” of Nikephoros Phokas describe combined-arms tactics with heavy cavalry, infantry, and horse archers.

The empire also controlled, at various points, parts of the Balkans and Anatolia that bordered or overlapped steppe-like grasslands. It hired and settled steppe peoples as federate troops. In the 10th and early 11th centuries, Byzantine armies under generals like John Tzimiskes and Basil II used mobile cavalry forces to good effect.

Our counterfactual hinges on the 11th century crisis. Historically, the empire lost much of Anatolia to the Seljuk Turks after the battle of Manzikert in 1071 and the civil wars that followed. Those losses stripped Byzantium of many of its best recruiting grounds for native cavalry and horse archers.

In the what-if version, the empire avoids or mitigates that disaster. Either Manzikert is a draw instead of a rout, or the political collapse afterward is less severe. The emperors keep control of central and eastern Anatolia, where they already had themes (military provinces) that produced cavalry.

Facing constant pressure from Seljuk and other Turkic horse archers, the Byzantines respond by transforming their own army. They expand the recruitment of native Anatolian horse archers, settle more Turkic groups inside the empire as military colonies, and invest in horse breeding on imperial estates. The tagmata, the central field army, becomes more cavalry-heavy, with a larger proportion of mounted archers integrated into each formation.

Economically, this is just within reach. Byzantium in its stronger centuries had a sophisticated tax system, a monetized economy, and imperial estates that could support horse herds. It could not match the raw horse numbers of the open steppe, but it could field a higher ratio of cavalry than most Western kingdoms.

Politically, it is tricky. Landed magnates in Anatolia already had strong local power. Giving them more mounted troops risks creating semi-independent warlords. The Komnenian emperors in the late 11th and 12th centuries historically balanced this by tying aristocrats closely to the imperial family. In our scenario, that balancing act becomes even more delicate as cavalry-rich families gain leverage.

On the battlefield, a more horse-archer heavy Byzantium could fight Turks on closer to equal terms. Instead of relying heavily on foreign mercenaries and Latin heavy cavalry, imperial armies might use their own mounted archers to contest the skirmish phase, screen infantry, and conduct deep raids into enemy territory.

This could change the map. A stronger, more mobile Byzantine army might hold more of Anatolia, slowing or even preventing the rise of some Turkish beyliks that later formed the core of the Ottoman state. The Seljuk Sultanate of Rum might remain a frontier principality rather than a major power.

It might also change the Crusades. If Byzantium fields effective horse archer forces, Western crusaders arriving in 1096–99 would be dealing with a more confident, less desperate empire. The First Crusade might be more tightly controlled by Constantinople. Later, a stronger Byzantine cavalry arm could resist or deter Latin aggression, perhaps avoiding the sack of Constantinople in 1204.

There is a ceiling, though. Even a horse-archer heavy Byzantium is still a settled, bureaucratic empire with cities, tax registers, and court politics. It cannot simply become a Mongol horde with Greek inscriptions. Its armies would still need infantry for sieges, garrisons, and defense of mountain passes. Its cavalry would be expensive to maintain and vulnerable to fiscal crises.

So what? A Byzantium that leans harder into mounted archers could survive longer, hold more of Anatolia, and reshape Turkish and Crusader history, but its urban, bureaucratic nature would still limit how far it could copy nomad warfare.

Scenario 3: What if the Islamic world fully embraced steppe warfare?

The third scenario is the least counterfactual. The medieval Islamic world already moved a long way toward steppe-style mounted archery.

From the 9th century onward, Abbasid caliphs in Baghdad imported large numbers of Turkic slave soldiers, or ghilman, from the Central Asian steppes. Many were trained as mounted archers. Over time, these troops and their descendants became military elites in their own right. In the 11th century, the Seljuk Turks, themselves a steppe people, took control of much of the Islamic Middle East. Their armies were built around mounted archers.

Later, in the 13th century, the Mamluk sultans of Egypt created a ruling military class of slave soldiers, many of them of Turkic or Caucasian origin, trained intensively in mounted archery. The Mamluks defeated the Mongols at Ayn Jalut in 1260 using a mix of horse archers and heavy cavalry.

So what is the counterfactual? Imagine that this trend is even more thorough and more unified. Instead of fragmented sultanates and emirates, suppose a single large Islamic empire, perhaps a stronger Seljuk or an early Ottoman-style state, manages to keep political control over Anatolia, Syria, Iraq, and Iran from the 11th through the 13th centuries, with mounted archers as its core.

Economically, this region has some advantages. Parts of Iran and Central Asia have steppe or semi-steppe zones suitable for horse breeding. The Islamic world also controls rich agricultural lands and trade routes, giving it tax revenue to pay for professional troops. A centralized sultanate could maintain a large corps of trained horse archers, supported by iqta (land grants) or direct salaries.

In this scenario, the state commits to a professional, highly trained mounted archer corps on a scale larger than the historical Mamluk or Seljuk systems. Instead of relying heavily on tribal levies, it keeps more of its cavalry under direct central control, with regular training in archery, maneuver, and combined arms tactics.

On the battlefield, that would make an already dangerous opponent even more formidable. Crusader states in the Levant, which historically survived for nearly two centuries, might be crushed more quickly if faced with a unified, professionally organized horse archer empire. The 12th century battles where Latin heavy cavalry sometimes managed to break through Turkish lines would become rarer if those lines were deeper, better drilled, and better supplied.

To the east, such an empire might resist the Mongols more effectively. Historically, the Khwarazmian Empire collapsed under Mongol attack in the 1220s, in part because of poor leadership and internal tensions. A more cohesive, long-lived Seljuk or related state with a strong mounted archer tradition might not stop the Mongols entirely, but it could blunt their advance, forcing them into longer, costlier campaigns.

There are trade-offs. A heavy reliance on a professional mounted archer elite risks creating a military caste with its own interests, as the Mamluks later showed. Sultans could find themselves dominated or overthrown by their own troops. The cost of maintaining horse herds and training facilities would strain the treasury in bad years.

Geography also matters. While parts of the Islamic world suit horse archers, others do not. Egypt is rich but not horse country on the same scale as the Eurasian steppe. Arabia has deserts that are hard on large horse herds. So the empire would still depend on specific regions for its cavalry base, making it vulnerable if those areas are lost.

Still, of all the regions, the Islamic Middle East already came closest to integrating steppe horse archery into a settled imperial framework. Pushing that trend a bit further is easier to imagine than turning France into Mongolia.

So what? A more unified Islamic empire built around professional mounted archers could have shortened the life of the Crusader states and slowed the Mongols, shifting the balance of power across Eurasia, but it would still wrestle with the political risks of a powerful cavalry elite.

Which horse archer world is most plausible, and how would it change things?

Of the three scenarios, the Islamic and Byzantine ones are the most plausible. They build on real trends: Turkic and Mamluk mounted archers in the Islamic world, and long-standing cavalry traditions in Byzantium. Latin Europe had the steepest cultural and ecological climb.

The limiting factors are the same everywhere. True steppe-style horse archer dominance needs three things: cheap horses, people raised in the saddle, and political structures that can mobilize and control them. Settled states can buy some of this with money and training, but not all.

Byzantium had the bureaucracy and some of the land. It could realistically have fielded more horse archers and held Anatolia longer. That, in turn, might have delayed or reshaped the rise of the Ottoman Empire. A stronger Byzantine buffer in Anatolia would have changed how Turkish power reached the Balkans and how the late medieval Christian world faced the eastern threat.

The Islamic world had the best mix of access to steppe manpower and rich agricultural cores. A more unified, mounted-archer heavy empire from Iran to Egypt could have made Crusader adventures far shorter and less successful. It might also have given the Mongols a harder time, forcing them into negotiated frontiers rather than sweeping conquests in the Middle East.

Latin Europe could have increased its use of light cavalry and mounted archers, and in some regions it did. Hungary, Poland, and later states on the steppe frontier adopted more of these tactics. But the dense patchwork of fields, hedges, and castles, along with the social prestige of the heavy knight, meant that Europe was always going to be a mixed-arms, fortress-heavy world rather than a horse archer playground.

One more constraint cuts across all scenarios: siege warfare. Even the best horse archers do not knock down stone walls by themselves. Medieval power rested on controlling fortified cities and castles. That meant infantry, engineers, and siege trains. Any state that tried to go “all in” on horse archers would discover, fast, that it still needed slow, expensive, unglamorous siege capability.

So the most believable alternate timeline is not one where everyone turns into Mongols. It is one where a few states, especially Byzantium and a big Islamic empire, field larger, better integrated mounted archer forces. Battles become more fluid. Raids are faster and deeper. Some famous defeats and victories change hands.

What does not change is the basic trade-off. Mounted horse archers were terrifying in the open field because they weaponized mobility and distance. Copying them meant paying in horses, training, and social change. Most medieval states, even in this what-if world, would still be arguing over budgets, recruitment, and who got to wear the heaviest armor.

So what? Thinking through these scenarios shows why mounted horse archers were not a universal solution: their power depended on ecology and society as much as on tactics, and even in a world that copied them more widely, castles, cities, and politics would still keep warfare from turning into one long Mongol raid.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why were mounted horse archers so effective in ancient and medieval warfare?

Mounted horse archers were effective because they combined speed, range, and endurance. They could hit enemies with arrows from beyond the reach of most infantry, avoid close combat by retreating, and use feigned flights to lure opponents into ambushes. Their armies were built on societies that bred many horses and trained riders from childhood, turning mobility into a strategic weapon.

Why did medieval Europe not widely adopt steppe-style horse archers?

Medieval Europe had less suitable grazing land for large horse herds, a social order built around heavily armored knights, and a dense network of castles and towns that favored mixed-arms warfare. While some regions used light cavalry and mounted archers, turning the whole of Latin Europe into a steppe-style horse archer culture would have required major economic and social changes that were unlikely under real conditions.

Did the Byzantine Empire use mounted horse archers?

Yes. The Byzantine Empire used mounted archers influenced by Hunnic, Avar, and later Turkic tactics. Imperial manuals describe cavalry who could shoot from horseback and fight alongside heavy cavalry and infantry. However, the empire never became a pure horse archer power, because it also relied heavily on infantry, siege warfare, and a bureaucratic tax system tied to cities and farmland.

Could any medieval state have matched the Mongols at horse archer warfare?

Matching the Mongols would have been very difficult. The Mongols drew on vast steppe lands, a culture where almost every man was a skilled rider and archer, and a disciplined military organization. Some states, like the Seljuk and Mamluk realms, came closer by integrating Turkic mounted archers into professional armies, but no settled empire had the same combination of ecology, social structure, and leadership that made Mongol warfare so devastating.