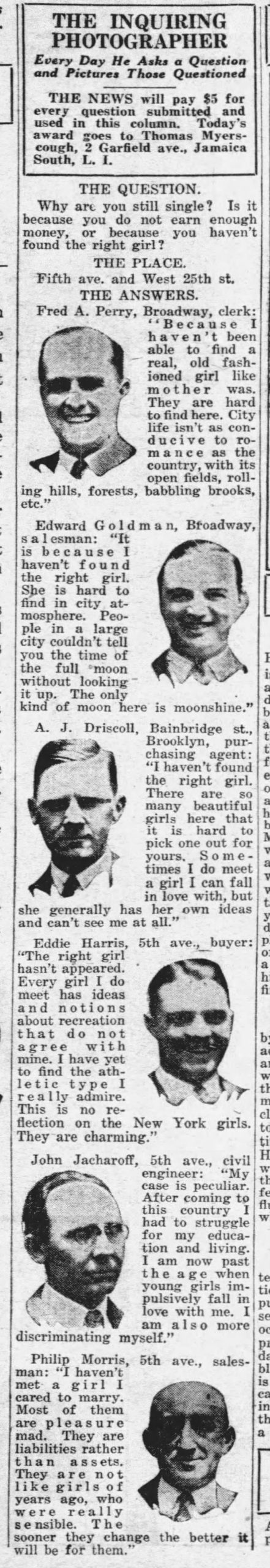

On a Wednesday in late May 1925, a New York newspaper sent its “Inquiring Photographer” into the streets with a simple question for men: “Why are you still single? Is it because you do not earn enough money, or because you haven’t found the right girl?”

He came back with portraits and quotes, the kind of human-interest feature that filled columns between war scares and stock prices. But that question captured something real. In the mid‑1920s, American men were marrying later than their fathers, worrying about wages, and eyeing a new kind of woman who bobbed her hair and wanted a job.

So what if their answers had been different? What if those 1925 bachelors had married earlier, or for different reasons, or not at all? And what would that have done to money, gender roles, and family life over the next century?

Why were so many men single in 1925?

To imagine different futures, you have to know the baseline. In 1925, the United States was in the middle of what people later called the Roaring Twenties. The war was over, the economy was humming, and cities like New York were swelling with young workers.

Census data from 1920 and 1930 show a pattern: men tended to marry a bit later than women. The median age at first marriage for men hovered around 24–26, for women around 21–23. That does not sound very old now, but it was a shift from the late 19th century, when rural norms and farm work pushed earlier marriages.

Several forces were at work:

• Money and work. Wages were rising on average, but they were uneven. A clerk or factory worker in New York might earn 20–30 dollars a week. Respectable middle‑class culture said a man should not marry until he could support a wife and children. That meant steady work, maybe a bit of savings, and often a rented flat of their own rather than a crowded tenement.

• Urban life and choice. In big cities, young men and women were no longer tied to family farms or small-town expectations. They could live in boarding houses, go to dance halls, and date more freely. That made it easier to stay single longer, or to be choosier.

• New women, old expectations. Women had just won the vote in 1920. College enrollment for women was climbing. Many worked as teachers, typists, or shopgirls before marriage. Yet the cultural script still said a man should be the main breadwinner and a woman should leave paid work when she married.

When the Inquiring Photographer asked, “Is it money or the right girl?”, he was tapping into a real tension. Men were caught between economic caution and new romantic ideals. Marriage was no longer just a practical alliance. It was supposed to be about love, compatibility, and, increasingly, fun.

That matters because any counterfactual about 1925 marriage has to reckon with this mix of old duty and new choice. Change one piece, and the rest moves.

Scenario 1: What if 1920s men had married much earlier?

Imagine the men the photographer stopped on the sidewalk in 1925 giving different answers. Instead of saying, “I don’t make enough” or “I haven’t met the right girl,” they shrug and say, “I’ll marry soon, money or not.”

For this scenario, assume that by the early 1920s, social pressure and policy push men toward earlier marriage. Maybe churches and civic groups run campaigns praising early family formation. Maybe employers start offering small “family wages” or housing allowances to married men. The result: the median age of first marriage for men drops a few years, to around 21–23, closer to women’s ages.

Economic strain at the bottom. The first impact would be felt in cramped apartments and boarding houses. A 22‑year‑old clerk earning 25 dollars a week who marries and has a child within a year is not building a nest egg. He is treading water. That likely means more extended families doubling up, more wives taking in laundry or boarders, and more children in crowded conditions.

Early marriage without higher wages does not magically create stability. It spreads one income across more mouths. That could slightly raise urban poverty rates in the late 1920s, especially among recent immigrants and Black families who already faced discrimination in hiring and pay.

Different Great Depression families. When the stock market crashed in 1929, an earlier-marriage cohort would be in a different place. Men who in our timeline were 24 and single might now be 24 with two children. That changes how the Depression hits.

• Relief programs in the 1930s often prioritized “heads of households.” If more young men were already married with children, a larger share of them might qualify for early relief or Works Progress Administration jobs.

• At the same time, more dependents per worker means more acute hardship when jobs vanish. Breadlines and eviction rates in big cities could spike even higher in 1930–1932.

There is a trade‑off: earlier marriage might slightly increase political pressure for relief, but it also deepens the pain when the economy collapses.

Impact on women’s work and autonomy. Earlier male marriage usually implies earlier female marriage. That would cut short many women’s years in the workforce. A 21‑year‑old woman who in our timeline might have worked as a secretary until 25 before marrying could now leave the office at 20.

That has knock‑on effects:

• Fewer years of wages and savings for women.

• Fewer women staying long enough in offices or professions to rise into supervisory roles in the 1930s.

• A stronger cultural association between womanhood and early motherhood, which could stiffen resistance to later waves of feminism.

Earlier marriage would also mean more children born before World War II. The famous “baby boom” after 1945 might be muted or shifted. Some of the children who were born in 1946–1950 in our timeline might have been born in the late 1930s in this one, to parents who married in the early 1920s.

By pulling marriage and childbearing forward, this scenario would make families larger and poorer in the short term and would slow the growth of women’s independent economic power. So what?

Scenario 2: What if 1920s men had stayed single much longer?

Now flip the script. Imagine that when the photographer asks why they are still single, many men answer bluntly: “Because I like it this way.”

In this scenario, urban culture and economics both push toward later marriage. Rents are high. Consumer goods are tempting. Movies, jazz clubs, and travel eat up disposable income. The idea of bachelor apartments and shared flats becomes glamorous, not pathetic.

By 1930, the median age at first marriage for men creeps up to 28–29, and for women to 25–26. This is closer to late 20th‑century norms, but arriving half a century early.

Different dating and gender norms. Longer single years mean more time dating. The 1920s already saw the rise of “dating” as a concept, with couples going out for entertainment rather than courting under parental eyes. Stretch that period and you get:

• More premarital sexual relationships, especially in cities.

• A stronger market for cheap restaurants, dance halls, and small apartments aimed at singles.

• A cultural script that treats the twenties as a time for self‑development and fun, not immediate family formation.

That last point is familiar today, but in 1925 it would have been jarring. Churches, parents, and moral reformers would push back. Some would warn of “race suicide” if native‑born Americans delayed childbearing while immigrant families had more children.

Women’s education and work expand faster. If men are not in a rush to marry, women have more reason to stay in school or on the job. A woman who expects to marry at 27 rather than 22 might:

• Finish college in greater numbers.

• Train as a nurse, teacher, or even lawyer and actually practice for several years.

• Accumulate savings and a sense of professional identity before marriage.

That would likely raise the share of women in skilled and semi‑professional roles by the 1930s. It might also normalize the idea that married women could keep working, since many would already have careers by the time they wed.

Fewer children, different politics. Later marriage usually means fewer children. If the average couple in this scenario has two children instead of three or four, the long‑term population growth of the United States slows slightly.

That could have subtle political effects:

• Smaller school‑age cohorts in the 1940s and 1950s.

• A less dramatic postwar baby boom, since many couples would already be in their thirties by 1945.

• Slightly less pressure for massive suburban expansion in the 1950s, though cheap cars and mortgages would still matter.

On the other hand, a larger pool of single adults in the 1930s and 1940s might feed into social movements. Unmarried men and women with jobs and no children are more likely to join unions, political clubs, and protest campaigns. The New Deal coalition might include a more vocal bloc of young, urban singles demanding labor protections and social insurance.

By stretching bachelorhood and single womanhood, this scenario accelerates trends toward individualism, women’s work, and smaller families. So what?

Scenario 3: What if money stopped being the main gate to marriage?

The photographer’s question framed the choice as money versus romance: “Do you not earn enough, or have you not found the right girl?” That reflects a deep assumption of the time. A man’s earning power was supposed to be the ticket into marriage.

What if that assumption had cracked in the 1920s?

In this scenario, two things shift:

• Women’s wages and job opportunities rise a bit faster, especially in clerical and retail work.

• Cultural norms soften around the idea that a wife must leave paid work after marriage.

The result is that by the late 1920s, a noticeable minority of young couples treat marriage as a partnership of two earners, at least for a few years.

Dual‑earner marriages before their time. There were already married women working in 1925, especially among the poor and among Black families in the South and North. What changes here is respectability. Middle‑class couples in cities might decide that both will work until they have saved for a home or until their first child reaches school age.

That would blunt the “I cannot afford to marry” argument. A 24‑year‑old man earning 25 dollars a week might marry a 22‑year‑old woman earning 18 dollars a week and share rent. Their combined income gives them more room than either alone.

Marriage becomes less of a single‑earner gamble and more of a joint economic project.

Different Great Depression coping strategies. When the Depression hits, dual‑earner couples have more flexibility but also face new risks. Employers in the 1930s often fired married women first, arguing that jobs should go to men. In this scenario, there would be more married women in offices and shops, so the backlash might be sharper.

On the other hand, if some employers and unions accept married women’s work as normal, families might weather unemployment better. If the husband loses his job, the wife’s income could keep the household afloat, or vice versa.

This could slightly reduce the number of families falling into destitution and might change how New Deal programs are designed. Policymakers might think more in terms of supporting households with mixed work patterns, not just male breadwinners.

Gender roles and later feminism. If middle‑class women in the 1920s and 1930s stay in paid work longer into marriage, the idea that a respectable woman can be both wife and worker gains ground earlier.

That would have ripple effects:

• More married women in unions and professional associations by the 1940s.

• More women with resumes and contacts when World War II opens factory jobs.

• A stronger base of women with their own earnings and bank accounts by the 1950s.

The “housewife ideal” of the 1950s, already more myth than reality for many, might be weaker. Popular culture could feature more working wives and fewer ads assuming that a woman’s entire world is the kitchen.

By loosening the link between male income and marriage, this scenario turns the photographer’s question on its head. The right girl is not someone a man can afford. She is someone who can afford him too. So what?

Which scenario is most plausible, and what would it change today?

Of the three, the third scenario is the most plausible given the real constraints of 1925.

Here is why.

Early marriage ran into hard economic limits. Wages in the 1920s were not high enough for most young men to support a family at 20 or 21 without help. Housing in cities was tight. Food and coal were not cheap. You could get some movement through moral pressure, but not a wholesale drop in marriage age without either higher wages or major subsidies that no one in Washington was proposing.

So a world of much earlier marriage would have required a bigger economic shift than was on offer.

Much later marriage clashed with strong social norms. On the other side, a big jump toward late‑20s marriage would have run into church teachings, parental expectations, and fears about “loose morals.” Some educated urbanites might have embraced it, but in 1925, large parts of the country still expected people to marry in their early twenties.

You could imagine a slow drift toward later marriage, but not a sudden leap. That drift did happen in the late 20th century, but it took decades of changing work, contraception, and culture.

Shared earning was already emerging at the margins. The third scenario, where money stops being the sole male gate to marriage, builds on trends that were already visible. Women’s labor force participation was rising. Typewriters and telephones had opened clerical jobs to women. Some couples were already quietly acting as dual earners, even if etiquette books frowned on it.

A modest cultural shift that normalizes married women’s work, especially in cities, does not require miracles. It requires a few influential employers, some popular novels or films with working wives, and perhaps a recession that makes single‑earner households look risky.

If that had happened, the long‑term effects on today’s world could be significant:

• The idea of the dual‑earner couple might feel less like a post‑1970s adjustment and more like a long‑standing norm.

• Women might have entered management, law, and politics in larger numbers earlier, since more would have had continuous work histories.

• The sharp “traditional 1950s housewife” image that still haunts debates about gender roles might be weaker, because it would have had less time as the dominant cultural script.

We might still argue in 2025 about work, parenting, and marriage, but the arguments would rest on a different story. Instead of treating the mid‑20th century male breadwinner model as the default that was later disrupted, we might remember the 1920s as the decade when couples first widely treated marriage as a joint economic project.

That is the quiet power of the Inquiring Photographer’s question. It caught a moment when money, romance, and gender expectations were all in play. Change how those 1925 men answered on the sidewalk, and you change who has money, power, and choices a hundred years later.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why were so many men single in the 1920s?

Many men in the 1920s stayed single into their mid‑twenties because of economic caution and changing social norms. Respectable culture said a man should not marry until he could support a wife and children, which required steady wages and housing. At the same time, urban life and new dating customs made it easier to delay marriage while looking for romantic compatibility rather than just a practical match.

Did men in the 1920s really avoid marriage because of money?

Yes, money was a common reason men gave for delaying marriage in the 1920s. Wages for clerks, factory workers, and service workers often made it hard to support a family without sharing housing or relying on relatives. Cultural expectations that the husband should be the main breadwinner made low or unstable income feel like a barrier, even when women were also working.

How would earlier marriage in the 1920s have changed the Great Depression?

If men had married earlier in the 1920s, more young families would have faced the Great Depression with children and few savings. That could have increased urban poverty and raised demand for relief, since more unemployed men would be supporting dependents. At the same time, earlier marriage would not have fixed low wages, so it likely would have deepened hardship rather than prevented it.

Could 1920s couples have been dual earners like today?

Some were, especially in poorer and Black families, but it was not widely accepted in the middle class. A plausible alternative path is that more employers and communities normalized married women’s work in offices and shops during the 1920s. That would have made marriage less dependent on a man’s income alone and could have given women more economic power and continuity in their careers decades earlier.