On a spring day in 1925, a New York newspaper sent a photographer into the streets with a question that should make your stomach turn.

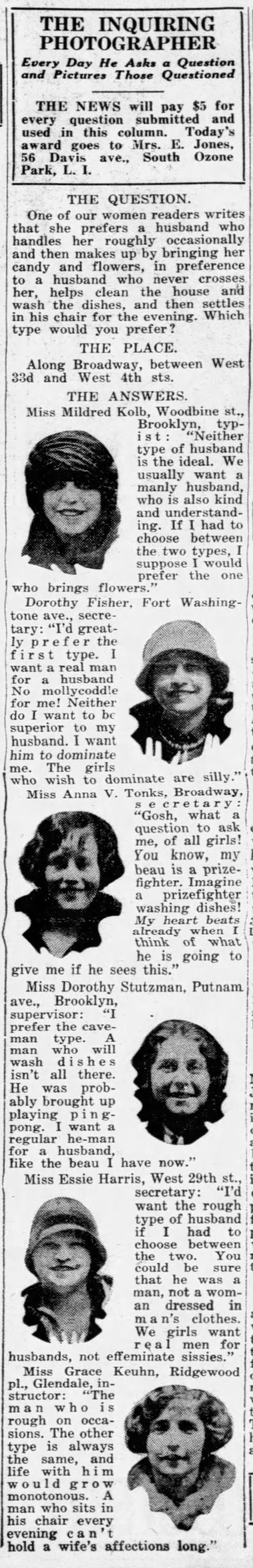

“One of our women readers writes that she prefers a husband who handles her roughly occasionally and then makes up by bringing her candy and flowers, in preference to a husband who never crosses her… Which type would you prefer?”

The feature was called “The Inquiring Photographer.” The premise was light. The subject was not. Domestic violence was turned into a personality quiz, something to banter about between ads for soap and corsets.

In 1925, marital rape was legal in every U.S. state. Police routinely sent battered wives back home. Jokes about “a good spanking” landed in cartoons and vaudeville. The question was not whether a husband had the right to “handle” his wife, but how much roughness was acceptable.

So what if that had been different? What if, at the very moment a New York paper was treating abuse as a quirky preference, American culture had gone another way and treated it as a crime and a moral outrage?

Domestic violence in the 1920s was widely normalized and legally tolerated. A very different response in that decade could have shifted U.S. law, policing, and gender norms for the rest of the century.

Why did 1920s America treat violence at home as a joke?

To imagine alternatives, you have to start with the world as it was.

In 1925, the United States had just given women the vote (1920), but not real equality in marriage. In most states, husbands controlled marital property and had wide latitude over household decisions. The common law idea of “domestic discipline” had been formally eroded in the 19th century, but in practice, police and judges still treated a man’s home as his domain.

Newspapers reflected that. “The Inquiring Photographer” was a regular New York feature that asked passersby a question and printed their portraits and answers. The tone was breezy. The editors knew exactly what they were doing when they framed abuse as a spicy personality choice. They were tapping into a shared assumption: a little violence, wrapped in romance, was part of married life.

Why did readers accept this?

First, the law. In 1925 there were almost no specific statutes against “wife beating” that were enforced with any consistency. Assault laws existed, but police often refused to apply them inside marriage. Marital rape exemptions were standard. A husband’s sexual access to his wife was treated as a given.

Second, economics. Many married women had no independent income. Even the new “flapper” generation, with its bobbed hair and short skirts, usually left paid work when they married. Leaving a violent husband meant poverty, social shame, and losing your children in court. That reality shaped what women told themselves they could “prefer.”

Third, culture. Freud’s ideas about female masochism were circulating in popular form. Hollywood films and popular fiction romanticized jealous, domineering men. Jokes about “a woman who likes a strong hand” were everywhere. When a woman reader wrote in to say she preferred a husband who “handles her roughly occasionally,” she was repeating a script she had been handed.

So the 1925 photographer’s question was not an outlier. It was a snapshot of a culture that normalized harm and wrapped it in candy and flowers. That baseline matters, because any alternate history has to push against those legal, economic, and cultural constraints.

So what? Understanding how deeply normalized abuse was in 1925 shows that changing attitudes would have required more than a few brave editorials. It would have taken law, money, and organized pressure.

Scenario 1: What if early feminists had made domestic violence their main fight?

In our timeline, the U.S. women’s movement of the early 20th century focused on suffrage, temperance, and basic legal rights. Domestic violence was present in their rhetoric, but usually as a side effect of male drunkenness or economic injustice, not as a central target.

Imagine a split in that history.

Say around 1910–1915, a cluster of high-profile cases hits the New York and Chicago papers. A judge refuses to grant a divorce to a battered woman. A husband kills his wife after years of documented abuse. A few reform-minded journalists, maybe someone like Ida B. Wells or a younger muckraker, decide to treat “wife beating” the way earlier writers treated child labor or tenement fires: as a scandal that demands reform.

That is not far-fetched. Progressive Era reformers loved causes that could be framed as moral crusades. They created juvenile courts, pure food laws, and anti-prostitution campaigns. Domestic violence could have fit that mold, especially if it was tied to protecting children.

Now add the suffrage movement’s infrastructure. By 1915, groups like the National American Woman Suffrage Association had chapters in dozens of cities, experience with lobbying, and sympathetic allies in state legislatures. In this scenario, a faction inside that movement decides that “the right to vote” must go hand in hand with “the right not to be beaten.” They start collecting affidavits from abused wives, publishing pamphlets, and lobbying for specific “wife assault” statutes with mandatory penalties.

What changes?

By the early 1920s, a few key states, probably in the Northeast and Midwest, could plausibly pass clearer laws: defining assault within marriage, removing marital rape exemptions in limited form, and funding small “refuges” for women and children. These would not look like 1970s shelters, but perhaps like expanded charity homes with a legal aid office attached.

Police training is still primitive, but reform-minded chiefs in big cities might issue orders that “wife beating” complaints must be recorded and referred to special magistrates. Newspapers, already primed by the earlier scandals, begin to cover high-profile prosecutions.

By 1925, when the Inquiring Photographer frames abuse as a preference, there is pushback. Maybe the paper runs an editorial the next week from a women’s organization condemning the question. Maybe a judge in the city has recently sentenced a man to six months for beating his wife, and that case is fresh in readers’ minds.

This does not erase abuse. It does change the range of what is sayable in public. The woman who writes that she “prefers” a rough husband now sounds less like a normal reader and more like someone defending the indefensible. Some readers still nod along. Others write angry letters.

So what? If early feminists had centered domestic violence, the 1920s could have seen the first serious legal and institutional pushback against marital abuse, making it harder for media to treat it as a joke.

Scenario 2: What if Prohibition had triggered a moral panic about wife beating?

There was already a ready-made frame for condemning domestic violence in 1925: alcohol.

The Women’s Christian Temperance Union and allied groups had spent decades arguing that drunken husbands ruined families. Their posters showed weeping wives and children, sometimes with black eyes. When national Prohibition took effect in 1920, many supporters saw it as a way to protect women from violent men.

In our reality, Prohibition enforcement focused on bootleggers, speakeasies, and organized crime. Domestic violence remained mostly a private matter. But the ingredients for a different path were there.

Imagine that by 1922–1923, official statistics and press reports start to claim that “wife beating” cases have not dropped after Prohibition, or have even risen as men drink illegal, stronger liquor. Reformers need a new angle to defend the dry law, which is already unpopular.

So they pivot. Instead of just saying “alcohol causes abuse,” they start saying “the state must protect women from violent men, drunk or sober.” They push for special “family courts” with the power to issue protective orders. They lobby for federal funds, tied to Prohibition enforcement, to create “protective bureaus” for women and children in major cities.

Politicians who want to save Prohibition from repeal seize on this. They hold hearings where battered wives testify. They invite doctors to describe the physical and psychological harm of repeated beatings. Newspapers, always hungry for drama, run sympathetic features. The phrase “wife beating” becomes a moral panic category, like “white slavery” had been a decade earlier.

By 1925, this panic has legs. Some states pass “habitual offender” laws that allow judges to jail men who repeatedly assault their wives. Social workers are hired to monitor high-risk homes. Police departments create small “women’s bureaus” that, in this scenario, are tasked not just with policing female offenders but with responding to domestic complaints.

Now picture that Inquiring Photographer question landing in that climate. You can almost hear the editor’s meeting. Someone pitches the question as edgy. Someone else worries it will look out of step with the new moral crusade. Maybe it still runs, but the paper frames it more carefully, or pairs it with a sidebar quoting reformers who condemn “rough handling.”

The key here is that the shift is not driven by feminism alone, but by a coalition of moralists, social workers, and politicians trying to shore up Prohibition. Their motives are mixed. Their impact is real.

So what? If Prohibition-era moralists had tied their cause to protecting women from violence, domestic abuse could have become a national scandal in the 1920s, forcing media and police to treat it as a public problem rather than a private joke.

Scenario 3: What if a sensational trial had changed the law in the mid‑1920s?

Sometimes a single case reshapes public opinion. Think of the Lindbergh kidnapping in 1932 and the resulting federal kidnapping law. Something similar could have happened with domestic violence in the mid‑1920s.

Imagine a case in 1924 or 1925 in a big media city like New York, Chicago, or Los Angeles. A middle-class woman, not poor and not an immigrant, kills her husband after years of documented abuse. Neighbors testify to screams and bruises. Doctors produce records. Maybe she had tried to get help from the police and was turned away.

In our timeline, there were such cases, but they rarely became national causes. In this scenario, a savvy defense lawyer and a women’s organization decide to make it a test case. They argue “battered woman’s self-defense” long before that phrase exists. They bring in early psychologists to talk about trauma. Reporters latch on.

The trial becomes a media circus. Cartoonists draw sympathetic images of the defendant. Editorials ask why the state protects abusive husbands more than their wives. When the jury acquits her, or convicts on a minor charge, the courtroom erupts.

Legislators, sensing public outrage, introduce “Battered Wife Relief Acts” in several states. These might do a few things:

• Make it easier for abused wives to get divorces without proving adultery.

• Allow judges to issue early forms of restraining orders.

• Clarify that assault laws apply fully within marriage.

Courts are still conservative. Police still drag their feet. But now lawyers have statutory language to cite. Women’s groups have a martyr figure to rally around. Newspapers have a narrative they like: the long-suffering wife who fought back.

By the time the Inquiring Photographer goes out in May 1925, readers have this trial in their heads. The question, “Which type of husband do you prefer?” now brushes against a recent, bloody story of what “rough handling” can mean. Some respondents might still treat it as a joke. Others might answer sharply that no husband has the right to lay a hand on his wife.

So what? A single sensational trial in the mid‑1920s could have created legal tools and public sympathy for abused women decades earlier, making it harder to romanticize violence in mainstream media.

Which alternate path is most plausible, and how far could it really go?

All three scenarios stay within the constraints of 1920s America. None imagines universal gender equality or modern trauma-informed policing appearing overnight. The question is which path fits best with the politics, economics, and media of the time.

The Prohibition-driven moral panic is probably the easiest to imagine. Reformers were already linking alcohol and domestic misery. Congress and state legislatures were already passing aggressive social laws. Turning “wife beating” into a headline-grabbing evil to justify Prohibition would have fit the era’s style of politics.

The early feminist focus on domestic violence is plausible, but it would have required a strategic shift. Many suffrage leaders were wary of being painted as anti-marriage. They often framed their cause as improving, not attacking, the family. Making abuse their main banner would have risked alienating moderate supporters. Still, a faction could have pushed it harder, especially after women got the vote and needed new issues.

The sensational trial scenario is almost a coin flip. Cases like that did happen. What they often lacked was a media environment willing to treat the wife as a sympathetic figure rather than a hysterical criminal. That, in turn, depended on the kind of groundwork imagined in the first two scenarios.

So the most plausible alternate history is a blend: temperance and Prohibition reformers push domestic violence into the headlines as a social evil, early feminists seize the opening to demand specific legal protections, and one or two big trials crystallize the issue in the public mind.

Even then, how far could it go by 1925?

Realistically, you might get:

• Clearer assault laws that explicitly include spouses.

• Early, limited challenges to marital rape exemptions in a few states.

• Small urban refuges for abused women, often run by charities.

• A norm in respectable newspapers that joking about “rough handling” is in bad taste.

You would not get widespread no-fault divorce, mass economic independence for married women, or fully trained domestic violence units in police departments. The economic and gender structures of the 1920s are too rigid for that.

But even those modest changes would have mattered. They would have given some women real options. They would have planted legal doctrines that later generations of lawyers could expand. They would have made it harder for a newspaper to present a reader who “prefers” a rough husband as just another voice in a harmless quiz.

So what? The most plausible alternate path is not a 1920s free of domestic violence, but a 1920s where the law, media, and reformers start challenging it decades earlier, softening the ground for the later women’s movement.

Why that 1925 question still matters now

It is tempting to read that 1925 Inquiring Photographer question and dismiss it as “just the times.” People did not know better, we tell ourselves. That is only half true.

Even in the 1920s, some women left violent husbands. Some judges granted divorces on grounds of cruelty. Some reformers talked about “wife beating” as a social evil. The idea that abuse was wrong existed. It simply did not dominate law, media, or politics.

That is what the counterfactuals expose. None of the alternate scenarios require modern values to be parachuted into the past. They require existing strands of thought to be taken more seriously, earlier, and by people with power.

They also force a harder question back on us. When we see modern media romanticize controlling partners, or treat “he’s just jealous” as a compliment, we are not as far from that 1925 question as we like to think. The line between “rough handling” as a joke and as a crime is drawn, erased, and redrawn in every generation.

The 1925 photographer probably thought he was asking a clever, slightly naughty question. Instead, he gave us a snapshot of what a society is willing to laugh off. Alternate histories remind us that those boundaries are not fixed. They are choices, made or not made, by people who could have acted differently.

So what? Looking at how 1920s America might have treated domestic violence differently is not about rescuing the past. It is about seeing how close the world came to a better path, and how much work it still takes to move from “preference” to protection.

Frequently Asked Questions

How common was domestic violence in 1920s America?

Exact rates are impossible to know, because most abuse was hidden and rarely recorded. Court records, social work reports, and memoirs all suggest that domestic violence was widespread across classes and regions. What we can say clearly is that the legal system and popular culture in the 1920s treated much of that violence as a private matter or even as a normal part of marriage.

Was marital rape legal in the United States in 1925?

Yes. In 1925 every U.S. state recognized some form of the marital rape exemption, the idea that a husband could not be prosecuted for raping his wife. This came from older English common law. Challenges to that exemption did not gain real traction until the late 20th century, and most states only removed it between the 1970s and 1990s.

Did early feminists talk about domestic violence at all?

They did, but usually indirectly. Many suffragists and temperance activists used images of battered wives and children to argue against alcohol or for women’s political rights. However, they rarely made domestic violence a central, standalone issue. Concerns about being seen as anti-marriage and the limits of their political capital pushed them to focus on suffrage, property rights, and labor protections first.

When did domestic violence start being treated as a serious public issue in the U.S.?

Domestic violence began to be treated as a major public and policy issue in the 1960s and 1970s, with the rise of second-wave feminism. Activists opened the first modern shelters, pushed for restraining order laws, and challenged police practices that ignored abuse. Some earlier reformers had condemned “wife beating,” but the sustained, nationwide focus on domestic violence as a human rights issue is a late 20th-century development.