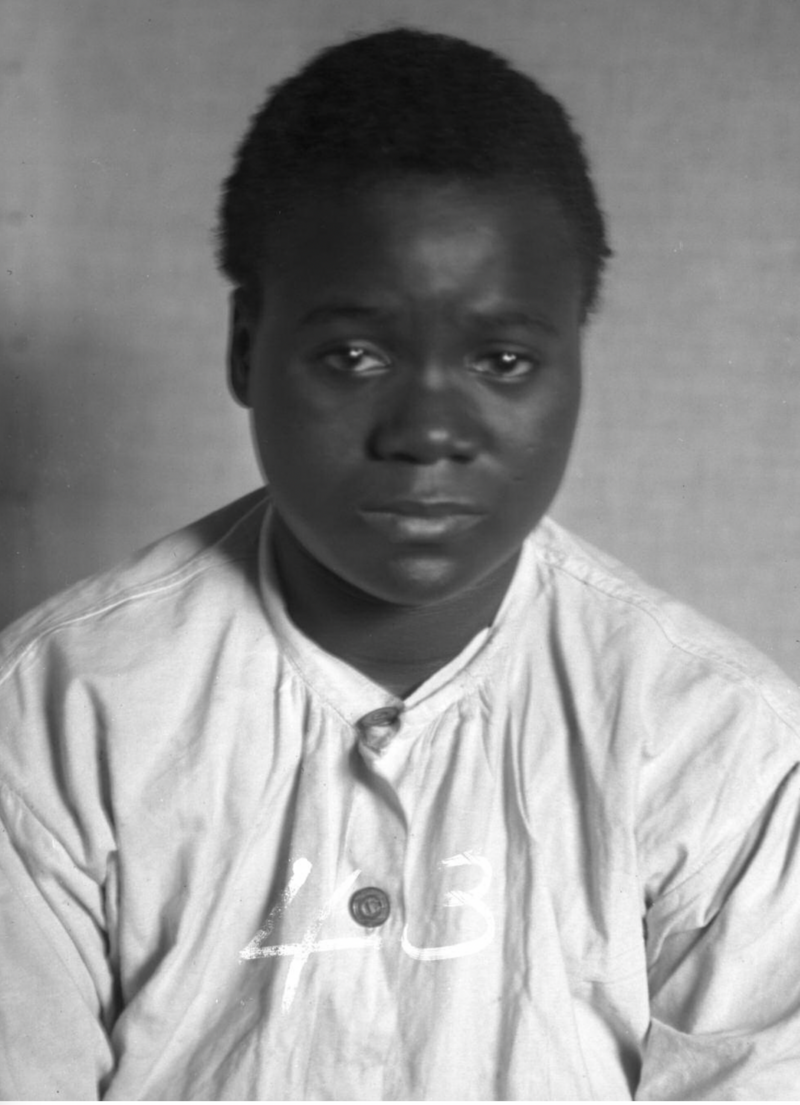

On the morning of August 16, 1912, a 17-year-old Black girl was led into Virginia’s electric chair. She had turned seventeen the day before. Her name was Virginia “Gennie” Christian, and she would be the last female minor legally executed in the United States.

She had killed her white employer, Ida Belote, after a violent confrontation in a Hampton laundry room. She said it was self-defense. An all-white, all-male jury took only a short time to decide she deserved death. The governor refused mercy. Then the state flipped the switch.

Virginia Christian’s case is often reduced to a grim trivia fact: the last executed female minor. The real story is messier and more revealing. It exposes how race, gender, poverty, and power shaped who lived and who died in Jim Crow America.

Here are five things her case tells us about American justice, then and now.

1. A 16-year-old laundress carried the weight of her family and her employer’s rage

Before she became a defendant, Virginia Christian was a working child. Born in 1895 to poor Black parents in Hampton, Virginia, she left school around age 13 when her mother became paralyzed. She went to work so her family could eat.

Her job: laundress for a white woman named Ida Virginia Belote. The pay was about four dollars a week. That was not pocket money. It was survival money. Her father and aunt warned her not to take the job. Belote, they said, had a violent temper and a reputation for abusing Black workers. The family needed the income, so Virginia went anyway.

On March 18, 1912, that simmering imbalance exploded. Belote came to the Christian home and accused Virginia of stealing a skirt. Virginia’s mother, unable to walk, told her daughter to go to Belote’s house and sort it out. That decision sent a teenager straight into a confrontation she did not control.

At the Belote home, the accusations escalated. Belote now claimed Virginia had taken not just a skirt but a gold locket too. Virginia denied it and threatened to quit. According to Virginia’s later confession, Belote attacked first, striking her with a spittoon. Virginia grabbed a broom handle and hit back.

In the chaos that followed, Belote ended up dead. Virginia said she stuffed a towel in her employer’s mouth to stop her screaming. The towel went several inches down the throat and Belote suffocated. Virginia took Belote’s pocketbook, which held about four dollars and a ring, and left.

This was the world of domestic labor in the Jim Crow South. Black girls and women worked inside white homes under white authority, with almost no legal protection. When conflict turned violent, the presumption of innocence did not travel with them.

So what? The killing was not just a crime scene. It was the collision point of child labor, racial hierarchy, and gendered power, and it set the stage for how the justice system would treat Virginia from that moment on.

2. Her “confession” and trial show how self-defense looked different for Black girls

Virginia was arrested the same day. She quickly confessed to the killing, but from the start she insisted it was self-defense. She described being hit with a spittoon, fighting back with a broom handle, and shoving the towel in Belote’s mouth to stop the screaming, not to kill her.

The journalist who recorded her confession, according to later accounts, was struck by how frightened and childlike she seemed. Others who met her described her as slow, possibly intellectually disabled. That would become a major point of debate, but not in time to save her.

Her trial moved fast. Virginia was indicted, tried, and convicted within months. She faced an all-white, all-male jury in a state where Black people were systematically excluded from juries through poll taxes, literacy tests, and outright discrimination. No one on that panel shared her race, gender, or social position.

Self-defense law did exist in 1912 Virginia, but it lived in a world where white fear and white property carried far more weight than Black survival. A white woman killed by a Black teenage domestic worker was not just a homicide. To white jurors, it looked like an assault on racial order.

Virginia’s defense argued for mercy, pointing to her age and circumstances. The jury heard that she had no prior arrests. They heard that Belote had a reputation for violence. It did not matter. The jury convicted her of murder and sentenced her to death.

In theory, the law treated self-defense as a universal right. In practice, who could claim it depended heavily on race, gender, and status. A 16-year-old Black laundress who fought back against her white employer was not seen as defending herself. She was seen as stepping out of her place.

So what? The trial showed that in Jim Crow Virginia, self-defense was not a neutral legal category. It was filtered through racial and gender expectations that made it nearly impossible for someone like Virginia to be seen as a victim fighting for her life.

3. The death sentence sparked rare biracial outrage, but the governor refused mercy

When the death sentence came down, it shocked people far beyond Hampton. Newspapers covered the case. Civil rights activists, Black community leaders, and even some white observers were appalled that the state planned to execute a girl who had just turned 17.

Virginia’s case drew comparisons to other young defendants, like later cases of George Stinney in South Carolina (executed at 14 in 1944) and Alexander McClay Williams in Pennsylvania (executed at 16 in 1931). In each, race, youth, and dubious legal process collided with the death penalty.

In 1912, petitions for clemency poured into the office of Virginia’s governor, William Hodges Mann. Mann was a Confederate veteran and a Democrat of the Jim Crow era. He had built a political career defending white supremacy in Virginia’s laws.

Journalists who had met Virginia, including the one who took her confession, joined the call for mercy. They described her as childlike, frightened, and possibly mentally impaired. Clergy wrote. Black organizations wrote. Some white citizens wrote too. They did not all agree on the facts, but many agreed that killing a teenage girl was wrong.

Governor Mann had the power to commute her sentence to life in prison. He refused. He also denied requests for a formal mental examination, despite the questions raised about her intellectual capacity. His public statements framed the case as a straightforward matter of law and order.

Executions are not just legal acts. They are political choices. Mann chose to send a message: the racial and social order would be defended with the harshest penalty, even when the condemned was a teenage girl with a credible claim of self-defense.

So what? The failed clemency campaign revealed both the limits of public sympathy in a Jim Crow state and the hard edge of gubernatorial power, which could have saved her life but instead reinforced a racialized idea of justice.

4. Questions about her mental capacity foreshadowed later bans on executing the disabled

Several people who met Virginia in jail believed she was intellectually disabled, though the language they used at the time was blunt and offensive by modern standards. They described her as slow, childlike, and unable to fully grasp what was happening to her.

There was no formal psychological evaluation. Governor Mann refused requests to order one. The court record does not show a serious inquiry into her mental state. She was treated as fully responsible, fully adult, and fully eligible for the electric chair.

Her final written message, often quoted in modern accounts, is haunting. She wrote that she believed she was “getting no more than I deserve,” that she was prepared to answer for her sins, and that she hoped to meet Mrs. Belote in heaven. She thanked those who tried to help her and said she blamed no one.

Whether that letter reflects resignation, religious teaching, confusion, or some combination is impossible to say with certainty. What is clear is that no one in power paused long enough to ask if she understood the process or could meaningfully assist in her own defense.

Decades later, the U.S. Supreme Court would rule that executing people with intellectual disabilities violates the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment. In 2002, in Atkins v. Virginia, the Court specifically barred such executions. The case came from Virginia, the same state that killed Virginia Christian ninety years earlier.

By modern standards, her case raises red flags: youth, possible disability, a chaotic crime scene, and a confession taken from a frightened teenager with little education. None of those were treated as reasons to stop the machinery of death in 1912.

So what? The ignored questions about Virginia’s mental capacity show how far the law had to move before recognizing that executing the intellectually disabled is unconstitutional, and they cast her death in an even harsher light when viewed through today’s standards.

5. Her execution helped end the practice of killing female minors, but her conviction still stands

Virginia Christian was executed by electrocution at the Virginia State Penitentiary in Richmond on August 16, 1912. She had turned seventeen the day before. Contemporary reports say she was calm, dressed in a simple prison garment, and that the execution was carried out quickly.

She would be the last female minor legally executed in the United States. After her death, states grew more reluctant to execute girls and very young women, even as they continued to execute teenage boys, especially Black boys, for decades.

Her case did not immediately change the law. There was no sweeping reform in 1912. But it lingered in public memory, particularly in Virginia. It became part of a pattern that later critics of the death penalty pointed to when arguing that the system was warped by race, class, and gender.

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, courts and activists revisited other child executions. George Stinney’s 1944 conviction for killing two white girls in South Carolina was vacated in 2014, with a judge calling his trial a “fundamental injustice.” Alexander McClay Williams’s 1931 conviction in Pennsylvania was vacated in 2022, after new scrutiny of the evidence and his coerced confession.

Virginia’s case has not been formally overturned. There has been no posthumous pardon, no vacated conviction, no formal apology from the state. Her story survives through newspaper archives, court records, and that single, stark fact: the last female minor executed in America.

Her case also sits in the background of later Supreme Court decisions that set age limits for the death penalty. In 2005, in Roper v. Simmons, the Court barred executions for crimes committed by anyone under 18. That ruling arrived 93 years too late for Virginia.

So what? Her death helped mark the outer boundary of what the public would accept, pushing the country away from executing girls and, much later, away from executing minors at all, even as her own conviction remains frozen in place.

Why the story of Virginia “Gennie” Christian still matters

Virginia Christian’s life was short and harsh. A Black girl pulled from school to support a disabled mother, sent into a white woman’s home despite warnings, caught in a violent confrontation she could not walk away from. The state responded by killing her and calling it justice.

Her case matters today for concrete reasons, not abstract lessons. It shows how easily self-defense claims can be dismissed when the defendant is young, Black, female, and poor. It shows how governors can use or ignore mercy. It shows how mental disability, when inconvenient, can be waved away.

It also explains why modern debates about the death penalty, juvenile justice, and racial bias are not theoretical. They are about real people who died in electric chairs and gas chambers, often after trials that moved too fast and cared too little.

When people ask how the United States ever executed children, or why so many Black defendants ended up on death row, Virginia “Gennie” Christian is part of the answer. Her story is not just a sad anecdote. It is a record of what the law once allowed, and a warning about what it can still excuse when power goes unchecked.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was Virginia “Gennie” Christian?

Virginia “Gennie” Christian was a Black teenager from Hampton, Virginia, born in 1895. At age 16 she killed her white employer, Ida Belote, during a violent confrontation and was convicted of murder. In 1912, one day after her 17th birthday, she was executed in Virginia’s electric chair, becoming the last female minor legally executed in the United States.

Why was Virginia Christian executed if she claimed self-defense?

Virginia Christian told authorities that she acted in self-defense after her employer, Ida Belote, attacked her with a spittoon. She admitted hitting Belote with a broom handle and stuffing a towel in her mouth to stop her screaming, which caused suffocation. Tried before an all-white, all-male jury in Jim Crow Virginia, her self-defense claim was effectively rejected, and racial bias, gender expectations, and her status as a poor Black domestic worker all contributed to the decision to sentence her to death.

Was Virginia Christian mentally disabled?

Several contemporaries who met Virginia Christian believed she was intellectually disabled, describing her as slow and childlike, but there was no formal psychological evaluation. Requests to the governor for a mental examination were denied. Because no proper assessment was done, historians cannot say with certainty, but her case is often cited in discussions about executing people with possible intellectual disabilities.

Has Virginia Christian ever been pardoned or had her conviction overturned?

No. Unlike later cases such as George Stinney in South Carolina and Alexander McClay Williams in Pennsylvania, Virginia Christian’s conviction has not been vacated or formally overturned. There has been no posthumous pardon from the state of Virginia, and her death sentence remains on the historical record, even as modern law now forbids executing minors and people with intellectual disabilities.