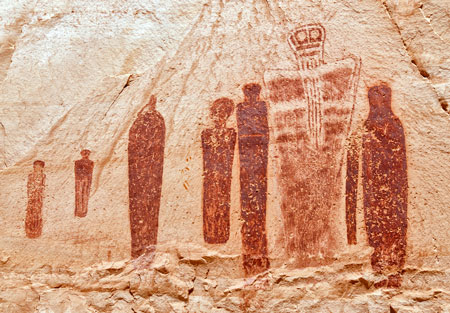

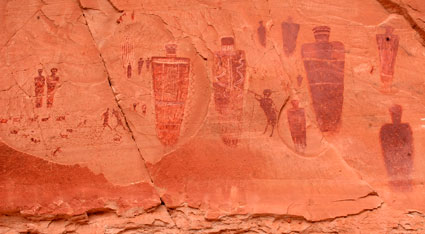

At Utah’s Canyonlands National Park, on a remote sandstone wall, limbless anthropomorphic figures look down like sentries on tourists and archaeologists alike. The orange-colored wraiths had, originally, been thought to be as much as 7,000 years old, but new testing has revealed a very different picture.

It’s one of the most iconic works of Ancient American art. The figures are larger-than-life size, and are considered the defining example of Barrier Canyon style. It’s called the Great Gallery, and experts have been debating for years about the artists who created the figures, and about just how old the figures might be.

Archaeologists wrote in the most recent issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that their discovery has finally ended the debate.

Rock art is horrifically difficult to date among all the types of art studied in archaeology. Usually, pictographs like the ones found in the Great Gallery are easier than most because they have pigments that can be tested, but… strangely enough, previous research at Barrier Canyon revealed that the ancient rock art there had no organic pigments. So, radiocarbon dating was out of the question.

But, our new team of archaeologists and research returned to Barrier Canyon with a trump card: a new technology called “optically stimulated luminescence dating”, and it’s proven extremely useful in determining when mineral deposits that have been buried were last exposed to sunlight, and not only that, but determining how long they were exposed for. It’s proved absolutely invaluable in dating the canyon’s rock art.

The international team of researchers was led by Utah State University archaeologist Joel Pederson, and they set about dating a maximum age for the Great Gallery by using their new technique to date the canyon floor. Two strata, or layers of sediment, that they studied told a story of important geological events.

The first layer they found tells a tale of a flood-driven sediment that originally filled the canyon far above the level of the Great Gallery. It stayed there until about 8,000 years ago. Over the following 5,000 years, the sediment was eroded away, exposing the sandstone panel that the Great Gallery was painted on. So, of course, the art had to have been younger than the top of that layer.

A second, newer layer of sediment was laid down between 3,000 and 800 years ago. This layer of sediment is what we now see as the modern canyon’s floor. It’s likely that this layer was a platform for the Great Gallery’s artists.

Between the two of these layers, a reasonable time frame for when the Great Gallery was created can be inferred, and the date is much younger than the original oldest proposed dates for the Gallery. So, the archaeologists knew that anything older than 5000 BC would be improbable, and anything much older than that was entirely impossible. So, how young might the artwork be?

They found that answer out by studying a remnant of the Great Gallery that had collapsed during an ancient, cataclysmic rockfall.

Using luminescence dating, the archaeologists tested the quartz grains from the face of the fallen rock, as well as the sediment that the falling rock landed on. Further study of the rock, and the archaeologists got lucky. An ancient leaf pinned between the sediment and the rock could be dated, too, using radiocarbon dating. These two dates provide a very solid minimum age constraint of AD 1100, the height of the Fremont culture in Colorado and Utah.

Now, there was one more point of data that could be used to pinpoint the date of the rock art even more accurately: bleaching. Luminescence technology can not only be used to measure the last time a mineral was exposed to sunlight, but also how long it was exposed for. The researchers determined that the rockfall had been exposed to sunlight for at least 700 years before it collapsed. That put the date for the artwork’s creation somewhere in the 5th century.

So, judging by all of their data, the artwork was created between 900 and 2,000 years ago, a period when immigrant groups from the Four Corners region were first moving into the area north of the Colorado River. They introduced the local cultures to agricultural techniques and village settlements. It was a time of change for the local Native American cultures.

It’s likely, then, that this dating has settled the debate not only of when the artwork was made, but who made it. The team concluded that it was made by peoples of contrasting heritage, where multiple cultures mingled together to form a larger society. Their rock art would, eventually develop into its own distinctive and geometrical style: the compelling work of the Barrier Canyon Style.