On a gray February morning in 1977, Indianapolis watched a man march through its streets with a shotgun wired to another man’s head.

The kidnapper was 44‑year‑old Tony Kiritsis, a small-time real estate investor who believed a bank and its loan officer had ruined him. The hostage was mortgage broker Richard O. Hall. A wire ran from the trigger of Kiritsis’s sawed-off shotgun to his own finger, and the barrel was lashed to the back of Hall’s neck. If police shot Kiritsis, his hand would spasm and blow Hall’s head off.

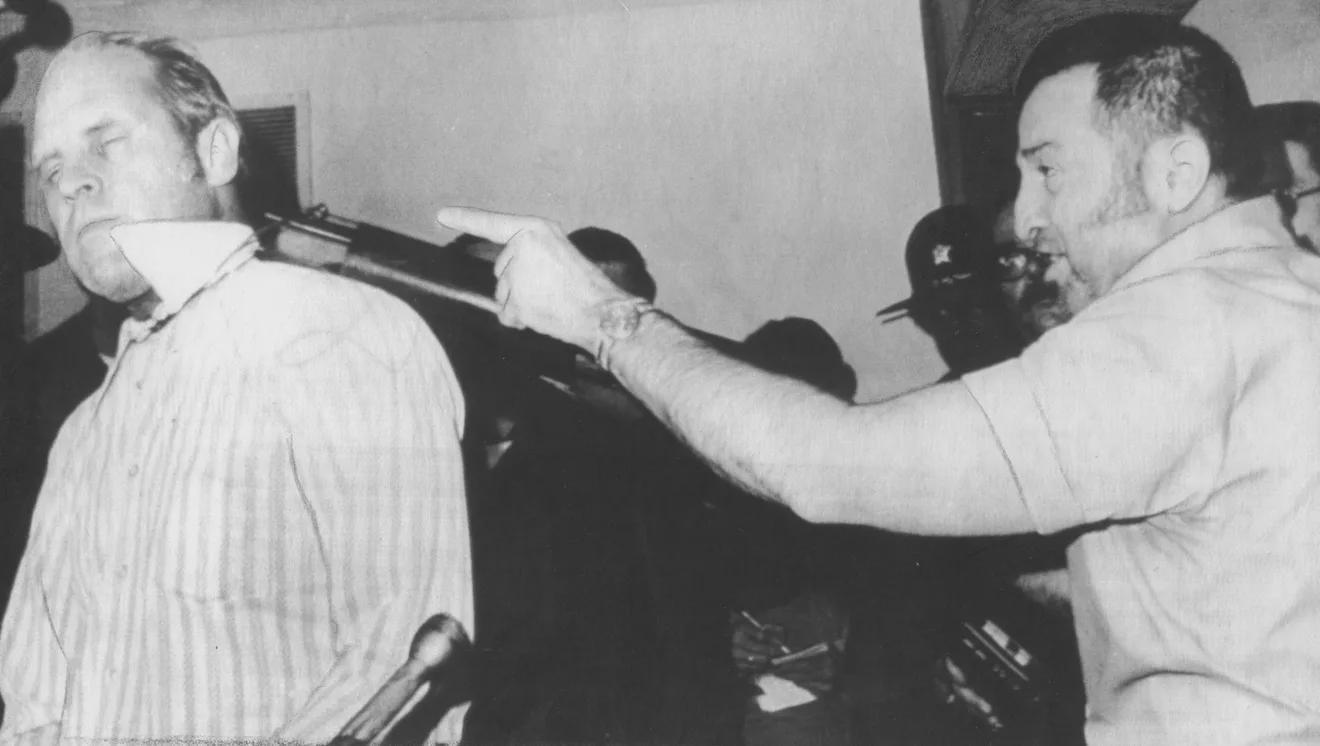

For 63 hours, the city, then the country, watched. The Pulitzer Prize-winning photo from that week freezes the horror: Hall’s face clenched in terror, Kiritsis wild-eyed behind him. The standoff ended without a death and with a controversial insanity verdict. But it could easily have gone another way.

The Tony Kiritsis hostage crisis was a live, televised collision of mental illness, financial desperation, and 1970s media ethics. The outcome shaped how police, courts, and newsrooms handled high-risk standoffs. Changing that outcome changes the story of American hostage policy and media restraint.

What actually happened in the Tony Kiritsis hostage crisis?

On February 8, 1977, Kiritsis stormed into the Indianapolis office of Meridian Mortgage, furious over a land deal and a loan he believed was predatory. He took loan officer Richard Hall hostage at gunpoint. Then he did something that made this case different from a standard armed kidnapping.

Kiritsis rigged a wire from the shotgun’s trigger to his own finger and tied the barrel to Hall’s neck. The device created what police negotiators later called a “dead man’s line.” If Kiritsis was shot, startled, or killed, the wire would yank the trigger. Hall would die instantly.

For three days, Kiritsis dragged Hall through the city, then holed up in his apartment. He called radio stations. He ranted on live television. He demanded that the bank publicly admit it had wronged him and that he receive a financial settlement. Police, terrified of triggering the shotgun, held back and negotiated.

The climax came on February 10. Surrounded by cameras and microphones in his apartment, Kiritsis read a long, angry statement on live TV. At the end, he suddenly announced he was not going to kill Hall. He had, he said, decided to let him go. He then dramatically released the shotgun mechanism and surrendered. Hall walked out alive.

In 1977, Indianapolis kidnapper Tony Kiritsis held mortgage broker Richard Hall hostage for 63 hours with a wired shotgun. He surrendered on live TV and was later found not guilty by reason of insanity. The case became a reference point for insanity defenses, media ethics, and police hostage tactics.

Kiritsis was charged with kidnapping and armed extortion. In 1978, a jury found him not guilty by reason of insanity. He spent years in a state mental hospital and was released in 1988. Hall survived, though by all accounts deeply traumatized. The photo of the shotgun wired to his head won a Pulitzer and burned the incident into public memory.

That real outcome matters because it created a rare example of a high-profile, televised hostage crisis that ended without bloodshed, and it fed a growing backlash against the insanity defense in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Scenario 1: What if police had taken the shot and killed Kiritsis?

One of the most obvious counterfactuals hangs over every frame of the photo: why did no one shoot him? In many hostage cases, police snipers look for a clean shot. In this one, they had a technical and ethical nightmare.

The shotgun was wired to Kiritsis’s finger. If he was hit, the fear was that his muscles would contract and pull the trigger. Forensic and tactical experts at the time did not have a clear, tested model for how that mechanism would behave. So officers erred on the side of not firing. But imagine an alternate moment.

Say a sniper, under pressure from city officials or fearing Kiritsis was about to pull the trigger, took the shot during one of the public walks or at the apartment. Two outcomes are most likely:

1) Kiritsis is killed and Hall dies instantly from the triggered shotgun. 2) Kiritsis is killed and, by luck or physics, the gun does not fire, leaving Hall alive.

If both men died, the public story becomes one of double tragedy and police overreach. The narrative shifts from “mentally ill man surrenders on TV” to “hostage killed in police rescue attempt.” In the 1970s, American policing was already under scrutiny after the civil rights era and the 1971 Attica prison uprising. A failed rescue with a dead hostage would have fed a national debate about when police should use deadly force in standoffs.

In that world, Indianapolis would likely have launched a formal inquiry into the decision to shoot. Police hostage policies, still relatively new, might have moved faster toward strict “contain and negotiate” doctrines that became standard in the 1980s. The Kiritsis case, instead of being cited as a negotiation success, would be cited as a cautionary tale about tactical impatience.

If Hall survived and Kiritsis died, the legal and political fallout would look different. There would be no insanity trial to fuel arguments about defendants “getting off” on mental health grounds. Instead, the story becomes one of a heroic rescue and a dead perpetrator. That tends to close off public discussion about mental illness and financial desperation, because the central actor cannot testify, cannot rant on the stand, cannot be examined by psychiatrists in public.

Either way, the Pulitzer-winning photo would be reinterpreted. Rather than a symbol of a crisis defused, it would be a prelude to a fatal shot. Journalists and editors, already uneasy about broadcasting live crises, might have pulled back faster from airing standoffs in real time if viewers had watched a man die on camera because of a tactical decision.

This scenario matters because a police decision to shoot, especially if it killed the hostage, would likely have accelerated national restrictions on live coverage of standoffs and pushed hostage doctrine toward stricter rules on when snipers can fire.

Scenario 2: What if Kiritsis had killed Hall on live TV?

Another chilling possibility lurked every minute of those 63 hours: what if Kiritsis had pulled the trigger himself, especially during the televised speech?

On the final day, Kiritsis invited reporters and cameras into his apartment. He ranted at length about being cheated by the bank. At one point, he put the shotgun to Hall’s head and shouted that he could kill him right there. In our world, he backed down and surrendered. In a darker branch of history, he does not.

Imagine that, mid-rant, he fires. The killing is broadcast live, unedited, into homes across Indiana and, via network feeds, across the country. Children see it. Politicians see it. Prosecutors see it. News executives see their worst nightmare.

Television news in the 1970s was still figuring out the boundaries of live coverage. The 1972 Munich Olympics massacre had already shown the dangers of broadcasting hostage situations, as terrorists watched their own coverage. A live execution in Indianapolis would have been a domestic shock of similar magnitude.

The first consequence would be a ferocious backlash against local stations that carried the feed. Congressional hearings on media responsibility in covering violence would be almost guaranteed. The Federal Communications Commission, which regulates broadcast licenses, would face pressure to set rules about airing live standoffs, suicides, and hostage crises.

Inside newsrooms, the lesson would be brutal and immediate: no more truly live coverage of volatile armed situations. Instead, a delay system becomes standard years earlier than it did in reality. Editors would insist on a time buffer to cut away if violence erupts. The Kiritsis case would be the cited reason every time a network declined to air a live police chase or standoff.

Legally, a live-on-air killing would harden public attitudes against insanity defenses. In the real case, jurors could weigh psychiatric testimony and see a man who had not actually killed. In this alternate case, they would have watched the murder with their own eyes. The pressure to convict, and to narrow the insanity defense in Indiana law, would be enormous.

That could ripple outward. The 1980s saw a national backlash against the insanity defense after John Hinckley Jr. shot President Reagan and was found not guilty by reason of insanity. A televised Kiritsis killing in 1977 would add fuel earlier. State legislatures might have tightened insanity standards in the late 1970s instead of waiting for the Reagan case.

For banks and lenders, the optics would be brutal. A hostage-taker killing a loan officer on live TV, while ranting about foreclosure and unfair terms, would make every small-town bank PR officer sweat. Industry groups might have pushed harder for quiet settlements in similar disputes to avoid copycats. At the same time, security protocols for loan officers and bank staff would likely have been upgraded faster.

This scenario matters because a live televised killing would have accelerated both media self-censorship around violent events and political efforts to restrict the insanity defense, changing how Americans saw mental illness and violent crime on their screens.

Scenario 3: What if Kiritsis had been convicted and sent to prison?

In reality, the jury accepted that Kiritsis was legally insane at the time of the crime. He was committed to a mental institution rather than prison. That verdict angered many people who saw a man who had planned a kidnapping, built a device, and negotiated publicly. They believed he knew what he was doing.

So what if the jury had gone the other way?

Suppose prosecutors persuaded jurors that the planning and execution showed clear intent, and that psychiatric testimony was not convincing. Kiritsis is found guilty of kidnapping, criminal confinement, and attempted murder or related charges. Given the severity and publicity, he likely receives a long sentence, possibly decades.

On the surface, this seems like a small change. One man goes to prison instead of a hospital. But the symbolic meaning shifts.

A conviction would have been cited by prosecutors around the country as proof that juries could and should reject insanity claims in dramatic cases. Defense attorneys would have a harder time convincing clients to pursue an insanity strategy in hostage or mass-violence cases, fearing a Kiritsis-style rejection.

Inside Indiana, lawmakers might feel less urgency to tinker with the insanity statutes, because the public would see the system as having “worked.” In our reality, the not-guilty-by-reason-of-insanity verdict fed a sense that the law was too lenient, which later blended into the national mood after the Hinckley case. A conviction would blunt that specific grievance.

There is also the question of Kiritsis himself. In a prison, a mentally ill, high-profile inmate with a history of extreme violence can become a management problem. If he deteriorated or harmed others, that would feed another debate: whether prisons were being used as warehouses for the mentally ill.

By the late 1970s, America was already deep into deinstitutionalization, closing many state psychiatric hospitals and pushing people with serious mental illness into jails, streets, and underfunded community programs. A convicted Kiritsis deteriorating in prison might have become a case study for critics of that trend.

For Richard Hall, a conviction might have brought a different kind of closure. Knowing his kidnapper was in a prison cell instead of a hospital bed could change how victims and their families talk about justice in cases involving mental illness. Victim advocacy groups, which grew in influence in the 1980s, might have pointed to the Kiritsis conviction as a model for “tough but fair” outcomes.

This scenario matters because a conviction would have shifted the symbolic weight of the case from a controversial insanity verdict to a story about punishment, affecting how later high-profile defendants and lawmakers thought about mental illness and crime.

Which alternate outcome is most plausible, and what would it change long term?

Not all counterfactuals are created equal. Some are barely a step away from what happened. Others require people to act wildly out of character or ignore strong incentives. So which of these alternate Kiritsis worlds sits closest to reality?

The most plausible change is Scenario 3: a conviction instead of an insanity verdict.

Juries in the 1970s were already skeptical of insanity defenses. The legal standard in Indiana required that the defendant be unable to appreciate the wrongfulness of his actions or conform his conduct to the law. Prosecutors had a strong argument that Kiritsis planned the crime, understood leverage, negotiated with police, and took steps to avoid being shot. Those are classic markers of legal sanity.

All it would have taken was one or two jurors persuaded that, however disturbed he was, he still knew right from wrong. That is a small shift in human judgment, not a radical rewrite of events.

By contrast, Scenario 1, a sniper taking the shot, runs against the documented caution of police on the scene. They were deeply worried about the wired shotgun. There is no evidence that commanders were close to authorizing a shot. It would have required a breakdown in discipline or a sudden misreading of Kiritsis’s intentions.

Scenario 2, a live-on-air killing, is psychologically possible. Kiritsis was volatile and angry. But his behavior across the 63 hours shows a man who wanted leverage and an audience, not a corpse. He repeatedly threatened to kill Hall yet did not. He seemed to want humiliation and a settlement from the bank more than murder. For him to suddenly execute Hall on camera would require a sharper break from that pattern.

If we accept Scenario 3 as the closest alternate path, the long-term changes are more subtle but still real. The Kiritsis case becomes a precedent for rejecting insanity in elaborate hostage crimes. Indiana’s insanity law might face less immediate pressure, which could, in turn, slightly soften the later backlash after the Hinckley verdict. Defense lawyers in the 1980s might cite Kiritsis less and other cases more.

Media behavior, police tactics, and bank security would likely evolve along lines similar to our reality, because the key visual, the wired shotgun photo, and the long standoff still happened. The difference is in how people talk about mental illness and responsibility when they point back to 1977.

That matters because high-profile cases like Kiritsis are not just local tragedies. They become reference points in arguments about insanity, policing, and media ethics for decades afterward. Change the verdict or the ending, and you change which arguments get the most ammunition.

The 1977 Tony Kiritsis hostage crisis is remembered for a single frozen image: a terrified mortgage broker with a shotgun wired to his head. Behind that image sits a chain of decisions by a desperate man, cautious police, and a jury wrestling with sanity and blame. The fact that no one died and that a jury chose insanity gave later Americans a specific story to tell about mental illness and mercy. In other nearby worlds, the same photo would lead into a story about police overreach, media horror, or unbending punishment. The stakes of that week in Indianapolis were not just one life or two. They were the stories we tell about what drives a man to wire a gun to another man’s neck, and what we decide to do with him after he puts it down.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was Tony Kiritsis and why did he take a hostage?

Tony Kiritsis was a 44-year-old Indianapolis man who, in February 1977, kidnapped mortgage broker Richard Hall. Kiritsis believed Hall and the bank had cheated him on a land deal and refused to extend his mortgage. In rage and desperation, he wired a shotgun to Hall’s head and held him hostage for 63 hours to force a public admission of wrongdoing and a financial settlement.

Did anyone die in the Tony Kiritsis hostage situation?

No. Despite the terrifying setup and repeated threats, no one died in the Tony Kiritsis hostage crisis. Kiritsis held Richard Hall at gunpoint for about 63 hours, often in public and on live TV, but eventually released him unharmed and surrendered to police. The lack of fatalities was unusual for such a high-risk, televised standoff.

What happened to Tony Kiritsis after the 1977 standoff?

After the 1977 standoff, Tony Kiritsis was charged with kidnapping and related offenses. In 1978, an Indiana jury found him not guilty by reason of insanity. He was committed to a state mental hospital rather than prison and remained under psychiatric supervision for years. Reports indicate he was released from institutional care in 1988, subject to conditions and monitoring.

Why is the Tony Kiritsis photo so famous?

The photo of Tony Kiritsis holding a shotgun wired to the head of Richard Hall is famous because it captures a rare, raw moment of a live hostage crisis in a U.S. city. Taken in Indianapolis in 1977, the image shows Hall’s terror and the bizarre wired gun device. It won a Pulitzer Prize and became a symbol of the dangers of live media coverage, the complexity of mental illness in crime, and the high stakes of police negotiation.