At one point during WWII, the only thing standing between the Nazi’s and nuclear weaponry was heavy water, an element they needed to facilitate a nuclear explosion. The Nazi’s had already sacked Norway, which meant they had control of the Vemork Hydroelectric Plant, a rich source of heavy water.

The allies had already drained the plant of heavy water prior to the sack, but that wouldn’t stop the German’s from producing more. We had to destroy the actual plant.

The solution came in the form of three operations, missions that almost failed. The clutch maneuver that succeeded was an operation called Gunnerside. It was the follow-up to two other missions, Grouse and Freshman. Grouse was a success, but Freshman left wrecked bombers and gliders in Norway. It put the survivors of the crashes in the hands of the torturous Nazi’s.

When the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) launched Operation Gunnerside, it was not only to save the soldiers still on the ground, but save the world from Nazi nuclear armament. It had to work.

Operation Grouse

To understand Gunnerside, you have to understand Operation Freshman. To understand that one, you have to know about Grouse. Operation Grouse was to function as part one to Freshman. At that time the Germans had no idea of the allies’ intentions, thus they kept little security covering Vemork.

October 18th, 1942. Leveraging intel from a technician inside the plant, whom the British had already smuggled out then returned via parachute, they successfully launched Grouse. There had been several previous attempts, all thwarted by bad weather, but in time it worked.

It was a simple plan; drop four men trained with all the intel received by their inside man. The four men were all Norwegian locals with substantial survival skills already, but the Brits trained them for war. From them, they learned sabotage and radio transmission.

Once dropped in Norway, the four men hiked for over two weeks until they could rendezvous with the brother of the inside man. That, however, was not their mission.

They were to set up for the cavalry, which would arrive with Operation Freshman. They needed to find a landing site for a couple of gliders, which they did, but they also need to plan the details of the attack on the plant.

Operation Freshman

Even without the German awareness of their plan, the allies were still in a pickle. The land around the plant was formidable enough.

There was little flat ground. The weather was a constant issue. Forest and vertical rises surrounded the plant and the neighboring village. It wasn’t just a matter of where they would land, but how they would attack the plant.

The Germans kept a thin defense, a reported a dozen men at the plant, twelve more at the dam and another 40 in a nearby village. Two men guarded the one bridge that spanned the valley to the plant.

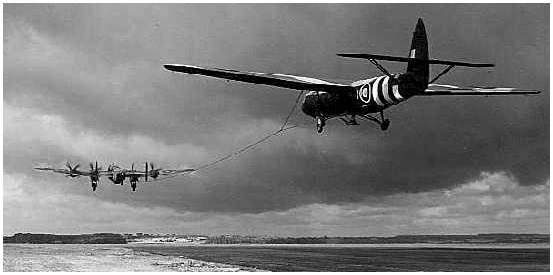

Unfortunately for the men of Operation Freshman, they would never get the chance to face these men. Two bombers towed two gliders a long way to Norway, through some ugly weather. Suffering from the trip and weather, the first bomber released its glider, then crashed into the mountains. Nobody from that bomber survived. The glider also lost control, but crash landed, leaving survivors.

The second bomber had trouble finding the landing site and chose to abort. As the bomber and glider turned to leave, the tow rope broke, leaving the second glider to crash land as well. There were survivors from that crash too.

Those who survived the crash landings might have preferred death. The Germans marched them through the cold, then interrogated, tortured and killed them. Operation Freshman was a failure.

Operation Gunnerside

With four men still in hiding, the allies had to regroup. Operation Gunnerside suffered no illusions. The Germans would now know of the ally interest in the plant by now. In fact, they’d even secured maps and plans for the attack in the wreckage from Freshman. Using that information, they fortified their security around the plant.

Where Freshman intended to land gliders, Gunnerside would repeat the success of Grouse by dropping more parachuters. Those soldiers were to rendezvous with the still-present Grouse soldiers, five, if you count the inside man. The allies still had their intel on the plant.

The Brits again trained six Norwegian soldiers, this time using a life-sized replica of the plant so the soldiers would know exactly where they were going. By the time the Gunnerside team landed, the Germans had mines, floodlights and plenty of security around the plant, but everything else was the same.

What the Germans did not count on was that anyone could climb down and cross the ravine below the single bridge. That’s just what the Norwegian team did. The six-man team took a few days to find the men from Operation Grouse, navigating the terrain of Norway on cross country skies. Once they found them, the team organized their plan of attack.

After climbing down the decline above the ravine, they crossed the freezing water, then ascended the hill using an old railway path. This routed them around the guards. Once inside the plant, they found an aging Norwegian caretaker who did not get in their way.

They set their explosives on every heavy water electrolysis chamber, left, then lit the fuses. Operation Gunnerside was a success. It destroyed what heavy water the Germans had, forcing them to start over, buying the allies time to attack again.

That’s just what we did. We hit them with a series of air raids, which were not so successful that we stopped the Germans from producing more heavy water, but we made them take drastic measures.

When they attempted to transport the heavy water they had, on the SF Hydro, three allied soldiers sank that ferry with explosives.

Had it not been for Operation Gunnerside, one can only guess what the Germans would have done with nukes. History records the actions of these soldiers as monumental to the ultimate success of the allies.