“The English are, as far as I know, the hardest worked people on whom the sun shines. Be content if in their wretched intervals of leisure they read for amusement and do no worse.” – Charles Dickens

Perhaps best known as one of the most influential writers of English literature to date, Charles Dickens was a man who sought to write about topics society didn’t want to see. His books, books like Oliver Twist, A Christmas Carol, A Tale of Two Cities, and Great Expectations appear in school book lists around the world. They’re dearly loved by bookworms, historians, and English teachers alike. They transcend the story of Western History, delving in to the gritty, darker sides of human nature and our story on this planet. But, who was Charles Dickens, really? Why did he start writing? Specifically, What was Oliver Twist all about and what kind of history inspired characters like Fagin and Bill Sikes, Dodger and Oliver and Nancy?

Early Life

Charles Dickens was born on bleak February 7, 1812, in Portsmouth in England. He had seven siblings, out of whom he was the second oldest. His father was a naval clerk and his mother was a teacher. Her parents dreamed of being rich, but never quite made it. His father had a horrible habit of living beyond his means, and was eventually sent to debtor’s prison when Charles was twelve. The teenager had to leave school to work at a factory along the smelly, dirty Thames. He earned six shillings a week, and that was all he could do to support his family. It marked a loss of his innocence, and soon a sense of utter betrayal, loneliness, and abandonment began to settle over the young boy. A year or so later, though, the family caught a break. His father came into an inheritance and was set free from prison, so Dickens was allowed to go back to school. Unfortunately, his father just kept accumulating debt, so when Charles was just fifteen, he had to drop out of school again and go work at an office to help support his family.

It turned out to be the best place he could have possibly ended up. Dickens began reporting at London’s courts within a year of being hired, and within two years, he was reporting for a few major London newspapers. His successes attracted a young lady named Catherine. The two would later marry and have a whopping ten children before being separated in 1858. Find more in-depth information about the life of Charles Dickens here.

Early Inspiration

Dickens first two published works: Sketches by Boz and The Pickwick Papers were wildly popular with readers. Dickens also began publishing a magazine called Bentley’s Miscellany. It was in this medium that reached hundreds of thousands of readers in London and the rest of England that he began to publish his first major novel, Oliver Twist.

It’s generally accepted that Dickens’ inspiration for Oliver Twist stemmed largely from his own childhood. The book is set in the underbelly of London and follows a young, abandoned orphan named Oliver. In his book, he details the mistreatment and exploitation of poor children in the workhouses, an institution that was supposedly doing good by keeping children off the streets of England. Dickens wrote a successful commentary on Victorian Society and the hypocrisy that was rampant at the time. Twist was hugely popular, and for the first time in English history, the eyes of the Victorian upper class were opened to the plight of London’s working class.

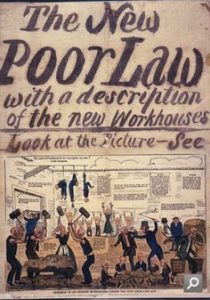

Oliver Twist and the Workhouses

The main themes of Oliver Twist center around the corruption of young children in Victorian society. One of the main influences, one of the overhanging palls on young Oliver’s life was the infamous workhouse. But what was a workhouse? How did they come into being, how were they run?

The Victorian Era was notorious for its employment of young children in dangerous factories, mines, and as chimney sweeps. Child labor was cheap, and it played an important part in the success of the Industrial Revolution. Young children of England’s working class were often expected to contribute to their family budget, working long hours in dangerous conditions for just a pittance. Orphans had it even worse. Many orphans were rounded up, collected, and stuffed into workhouses. These workhouses fed them, clothed them, and put a roof over their heads, but they worked from dawn to dusk in factories, didn’t get paid, and were hardly ever fed enough. Children as young as four were put to work. Generally, most died before they ever reached the age of twenty-five. They worked 16-hour days. Often they were set strict quotas and were beaten or locked away in small dark rooms when they couldn’t make them. The workhouses were ridden with disease, and there was usually only one ineffective doctor or nurse per hundreds of children and adults.

Reformation

Thanks to Charles Dickens’ novel, Oliver Twist, people became more and more aware of the terrible conditions of the workhouses and were outraged by the child labor that fueled their society. As early as 1802 and 1819, Factory Acts were passed to limit the working hours of workhouse children in factories and cotton mills to 12 hours a day. These acts weren’t very effective. But, as agitation toward the mistreatment of children kept stirring, less and less children were put into the workhouses. Due to a wave of laws passed regulating the workhouse infirmaries, requiring that the workhouse doctors serve not only residents, but the community around them, most workhouses began to turn into hospitals and homes for the elderly. Finally, in 1929, an act was passed that allowed the government to take over workhouses and turn them into municipal hospitals at their discretion. By 1948, in the National Assistance Act, the workhouses were finally completely abolished. Most of the buildings were converted into care homes for the elderly, or real shelters for the homeless. By the 1990s, the workhouses had completely, utterly disappeared from the face of England and people trapped in poverty were no longer being taken advantage of, but were actually getting the help they needed.