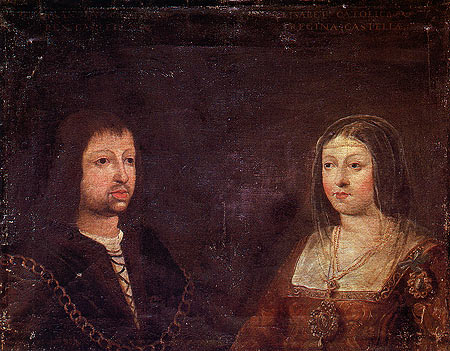

Isabella I of Castile ruled as Queen of Castile and León from December 11, 1474 until her death on November 26, 1504. Though she struggled to claim the throne for herself, Isabella brought down her country’s crime rate, reorganized the government, and lifted Spain back up from the debt her elder half-brother, Henry IV, had left it in. With her husband, Ferdinand, Isabella is best known for starting the Spanish Empire in 1492 when they sponsored Columbus on his journey west.

Born April 22, 1451 in Madrigal de las Altas Torres to John II of Castile and Isabella of Portugal, Isabella was second in line to the throne. Henry (later Henry IV of Castile), her half-brother who was more than twenty-five years her senior, was first in line. At the time, Henry had been married for about eleven years at the time to Blanche II of Navarre without any children. Their daughter, Joanna la Beltraneja (1462-1530), was later Queen consort of Portugal when she married King Alfonso V. Alfonso was Isabella’s younger brother, born two years after her in 1453. This took Isabella’s place down from second in line to third.

John II of Castile died in 1454, three years after Isabella was born and only one after Alfonso. When their half brother descended to the throne, they were placed in his care. Shortly after, Isabella, Alfonso, and their mother, Isabella of Portugal, moved to Arévalo, Spain. However, the living conditions at the castle in Arévalo was terrible and poor. Isabella and her family suffered through a shortage of money during this time. This was mainly because Henry refused to follow his father’s will. Before his death, John II had arranged that his children would always be financially taken care of. Henry most likely did not comply to his father’s wishes to keep his half-sibling away and restricted, or from ineptitude. Isabella’s mother still made sure that Isabella was instructed in religious lessons, despite their poor living conditions.

Henry’s wife, Joan of Portugal, was about to go into birth in 1461 to their first, and only, child, Joanna. Both Isabella and Alfonso were summoned to court, where they were under the king’s direct supervision while they finished their education. Isabella had become a member of the Queen’s household and her brother was placed under the care of his tutors.

Though the living conditions in Segovia were a huge improvement compared to those in Arévalo, Henry still kept a close eye on her. Isabella was forbidden to leave Segovia and he tried to keep her away from any political turmoil in his kingdom. The castle she resided in was adorned with gold and silver and she always had fresh food and clothing. She continued to go through basic education, which included: art, chess, dancing, embroidery, grammar, mathematics, music, religion, spelling, and writing. With her ladies-in-waiting, Isabella stayed entertained with art, embroidery, and music. For the most part, she lived comfortably and relaxed in Segovia, but did not have all sorts of freedom because of her older half-brother.

Noblemen in Segobia were anxious for power and demanded that Infante Alfonso, Henry-s younger half-brother, be named second in line to the throne. Some of them even told Alfonso to seize the throne himself. The nobles took control of Alfonso and persisted that he was the true heir. At the Second Battle of Olmedo in 1467, Henry went up against Alfonso and the nobility who supported him. In the end, the battle was a draw. Henry finally agreed, stating that Alfonso would be made his heir if he married Joanna, his daughter. Alfonso and Joanna married shortly after, but he died, most likely from the plague, in July of 1468. Suspecting that Alfonso had been poisoned, the nobleman asked Isabella, Alfonso’s successor, to take over her brother’s role as champion of the rebellion. Isabella instead preferred to negotiating a settlement instead of continuing with the war as the rebels began to lose support. So, Isabella and Henry met at Toros de Guisando and were able to come to a compromise. Henry would name her his heir-presumptive instead of Joanna and the war would stop. Henry was also not allowed to force Isabelle into a marriage, she just had to have his consent. In the end, the rebels and Isabella mostly got what they wanted from the compromise, though their main goal seemed to be getting Henry off the throne. Isabella had wanted to stay safe and not jeopardize her new position. Along with that, the rebels weren’t powerful enough to depose of Henry anyway.

When she had been only six years old, Isabella made her first appearance in the “matrimonial market” when she became betrothed to John II of Navarre’s young son Ferdinand. Both John and Henry supported tis match and were especially eager because of the alliance it would provide. But, the betrothal lasted only a short time. In 1458 when Isabella would’ve been not quite seven, Ferdinand’s uncle, Alfonso V of Aragon, passed away. Alfonso’s Spanish territories and the islands of Sicily and Sardinia were left to John, Ferdinand’s father when he became King John II of Aragon. Because of his stronger position, John no longer needed the alliance with Henry. Instead, Henry arranged a secret alliance with Charles of Viana, John’s older son. A big part of this new alliance was that Isabella was to marry Charles. John II was furious when he found out about this because the betrothal between Isabella and Ferdinand was still technically valid. Charles was thrown in prison for plotting against his father and then died in 1461.

Another attempt for an alliance was made when Henry tried to arrange for Isabella to marry Alfonso V of portugal in 1465. The Queen and Count of Ledesma approved of the alliance, but Isabella did not. She refused to consent to the match. When a civil war in Castile broke out due to Henry’s poor role as king, he tried to find a way to please the rebels. Trying to restore peace in his kingdom, Henry arranged for a marriage between Isabella and the Master of the Order of Calatrava, Pedro Girón Acuña Pacheco. Don Pedro would give a large sum of money to the royal treasury in return for the match. Henry quickly agreed, but Isabella was aghast. She prayed to god that she would not have to marry Don Pedro. On his way to meet with her in 1466, he became ill and quickly died, Isabella’s prayers being answered.

On September 19, 1468, Isabella was recognized as Henry’s heir-presumptive. Part of their agreement was that he could not force her into a marriage. More proposals and arrangements came, but none went through. Isabella refused every single one, promising to herself that she would marry Ferdinand of Aragon, her cousin and the first boy she was betrothed to. Henry tried to set up an alliance with Charles, Duke of Berry, the brother to Louis XI of France, but once again, she refused. At the time, Isabella and John II were secretly negotiating for her to marry Ferdinand. The formal betrothal took place on October 18, 1469. Isabella and Ferdinand were second cousins, so they had to stand within the prohibited degrees of consanguinity. Unless they obtained a dispensation from the Pope, the marriage would not be legal either. Their marriage was made legan within the third degree of consanguinity when they were presented with a supposed papal bull by the late Pius II.

Using the excuse of visiting her brother Alfonso’s tomb in Ávila, Isabella and Ferdinand eloped away from court and the king. Ferdinand made his way into Castile secretly disguised as a servant. On October 19, 1469, they were immediately married in Valladolid in the Palacio de los Viveros. Together, Isabella and Ferdinand had five children and one miscarriage and another stillbirth. Isabella, their first daughter, was born in 1470 and died in 1498, followed by a miscarried son in 1475, and a son named John in 1478 who then died in 1497. Their daughter, Joanna, born in 1479, later became Queen of Castile before her death in 1555. Isabella gave birth to twins in 1482, one they named Maria (1482-1517) and the other was stillborn. Their last daughter, Catherine, was born in 1485 then died in 1536. Catherine was the first of the infamous Henry VIII’s six wives and was mother to Mary I of England.

On December 11, 1474, Isabelle ascended to the throne as Queen of Castile and León after Henry’s death that same day. Ferdinand served as her co-monarch, King of Castile and León. There were already many plots against her after being named her brother’s successor. Diego Pacheco, Marquis of Villena and his followers strongly believed that Isabella did not belong on the throne and that Henry’s daughter Joanna was the rightful queen. The Archbishop of Toledo, who had always supported Isabelle, left court to meet with the Marquis after he made his claim known. The two of them plotted for Infanta Joanna to marry King Alfonso V of Portugal, her uncle, so they could claim the throne for themselves by invading Castile. Alfonso and Joanna married in May of 1475, starting the war between Spain and Portugal.

For the first year, the war went back and forth. At the Battle of Toro on March 1, 1476, both sides claimed their victory. The outcome may have been uncertain, but the battle represented a great political victory for the Spanish. Isabella took advantage of it and convoked courts at Madrigal-Segovia from April to October of 1476. Isabella, her oldest child and daughter, was sworn as the heiress to the crown of Castile. As rebellion broke out in Segovia that August, Isabella continued to prove that she was a powerful ruler when she rode out to suppress it while Ferdinand was off fighting in the war. Her advisors had told her not to go, but she did so anyways all by herself and negotiated with the rebels. Quickly, Isabella had been able to end the rebellion. When her son John, Prince of Asturias was born in June of 1748, this legitimized her place as the ruler to many.

The naval Battle of guinea was fought that same year and was a decisive victory for the Portuguese. The War of the Castilian Succession continued on. In the end, it was a Castilian victory on land, but a Portuguese victory on sea. Four treaties were signed on September 4, 1479 at Alcáçovas. Isabella and Ferdinand had to accept that Joanna live in Portugal and they give up the Portuguese crown. The Portuguese agreed to give the throne to Isabella if they were given Castile’s Atlantic territories except for the Canary Island along with a large compensation.

Because of the bad state Castile was in due to Henry, Isabella had to work on reform for her country when she first became queen in 1474. She focused on regulating crime after it was said that her brother and predecessor allowed many crimes to go unpunished. Historians now describe her as being inclined to justice more so than to mercy because of the measures she used upon becoming queen. Her husband, Ferdinand, was much more forgiving than Isabella, who was the opposite when it came to crime.

Her first major act in reform though was in 1476 when she began to use the police force, La Santa Hermandad, which translates into the Holy Brotherhood. The Hermandad had been in Castile for some time, but Isabella was the first monarch to use the police force. Instead, members of the nobility ad been in charge of keeping things under control, not the police and other royal officials. During the Cortes of 1476, Isabella established a general Hermandad to operate in Castile, Leon, and Asturias. The following year, Isabella also traveled to introduce her new police force to Extremadura and Andalusia. Two officials were also charged with restoring pace in the province of Galicia, which was full of robbers on the highways and in small towns. These officials turned out to be quite successful and drove more than 1,500 robbers out of Galicia.

Castile had been left in great debt as well from Henry IV’s reign, as he was known to be a lavish spender. To make more money, Henry had been selling off the royal estates for cheap prices, being one of the main causes for so much of the country being in poverty. Isabella was reluctant to follow the Courtes of Toledo’s conclusion saying that the only way to improve the financial state was to lay in a resumption for the alienated lands that Henry had sold. It was decided upon that the Cardinal of Spain would then hold an enquiry into the tenure of the acquired estates during Henry’s time as king. The royal treasury gained more and more money as the nobility paid large sums for their estates. One of the other issues Castile was facing financially was over production of coinage from Henry raising the number of mints from five to one-hundred-fifty. Isabella established a monopoly over royal mints in just the first year of her reign. She shut down many of the mints producing worthless coinage and took control over money production. By doing this, the public’s confidence in the crown handling the kingdom’s finances were restored.

Isabella and Ferdinand established hardly any new institutions in their kingdoms’ government. Their main achievement in Castile was use the existing institutions more effectively. Isabella began taking a firm grip of the royal administration in the 1470s. She made sure the senior offices of the royal household were honorary titles held by nobility only. Senior churchmen were often given secretarial positions. The nobility may have held titles, but those who did not come from noble families were usually the ones doing the real work. Isabella also made many reforms in 1480 during the Cortes of Toledo to the Royal Council, which was the traditional main advisory to the rulers of Castile. Instead of two distinct overlapping categories, she completely eliminated the second category, which held a less formal role and depended on the political influence of the individual. The first category was made of people with judicial and administrative responsibilities. Isabella did not care for bribes and favors so she made sure the second councillor, made up mainly of nobility, only attended the council of Castile as observers.

More than ever before, Isabella also came to rely on professional administrators, which were men who normally came from lesser families. She rearranged the council so that the nobles were no longer involved with direct matters of state. By doing this, Isabella hoped that she would weed out the members of the nobility who did not care much for the state. She realized that she needed to have a personal relationship as the monarch with her subjects. Every friday, time was set aside for Isabella and Ferdinand to sit allow people to come up to them with their complaints. Castile had never before seen this personal form of justice. The Council of State was also reformed to put the monarchs in charge. These many reforms made by Isabella may have seemed to be making the Cortes stronger, but it turned out that the Cortes was losing political power. Isabella and Ferdinand began moving towards having a non-parliamentary government, the Cortes becoming a nearly passive advisory body. Alfonso Diaz de Montalvo was hired directly by Isabelle to clear away any legal issues and compiling the remains into a comprehensive code.

Granada was the only place left for Isabella and Ferdinand to conquer at the end of the Reconquista. Since the mid-thirteenth century, The Emirate of Granada was held by the Muslim Nasrid emirate. Granda had been protected by natural barriers and fortified towns, keeping it from being conquered during the long reconquista. Isabella and Ferdinand reached Medina del Campo on February 1, 1482, which has been considered the general beginning of the war for Grenada. Granada’s leadership had been divided all along and they were never able to show a unified front, whereas Isabella and Ferdinand stayed very involved in the war right as it began. After ten years though, they had finally conquered Granada in 1492. Isabella and Ferdinand entered Granada to receive the keys of the city on January 2, 1492. Later that year, they also signed the Treaty of Granada, promising to let the Muslims and Jews on the island live peacefully.

By recruiting soldiers from all over Europe and improving their artillery, Isabella and Ferdinand were able to build up a much stronger army. Piece by piece, they continued to take their kingdom. After only a brief siege lasting two weeks, Ronda fell to Spain in 1485. Loja was taken the following year in 1486 when they captured Muhammad XII then released him. After that, Málaga fell to Spain. At this point, the whole of the western Muslim Nasrid kingdom fell back to Spain. The east followed when Baza fell in 1489. In the spring of 1491, they began the siege of Granada. Muhammad XII surrendered at the end of the year.

Queen Isabella is perhaps most notable for working with Christopher Columbus. Three months after she and Ferdinand entered Granada, she agreed to sponsor Columbus on his goal to sail west and reach the indies. They agreed to pay him a sum of money for his expedition. Columbus and his crew set sail on August 3, 1492. On October 12, he landed on an island he named San Salvador that is now known as Watling Island. the following year, he returned to Spain and presented what he had found to Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand. He brought natives of the island and gold back with him, welcomed like a hero. Isabella sponsored him right from the start, but there is no evidence of royal payments to him until 1493 when he returned.

From then on, Spain had entered their Golden Age for exploration and colonization, the period of what we now know as the Spanish Empire, which was established in 1492 and lived on until 1975. King John II of Portugal threatened the Spanish that he would send an army to claim the land Columbus had come across for himself because the land was on Portugal’s part of the world. Isabella and Ferdinand agreed to divide the Earth into parts in 1494 under the Treaty of Tordesillas. Isabella did not agree with Columbus enslaving natives from the Americas though. She tried to enforce new policies of the Canaries so that all people of the land were subjects to Castile and could not be enslaved. These laws and principles did not have much effect during her lifetime though.

Isabella was in opposition of taking on harsh measures against the Jews in Spain. The Dominican friar Tomás de Torquemada was able to convince Ferdinand to take harsh measures against them economically though. The Alhambra decree was issued on March 21, 1492 and expulsion of the Jews ensued. They had three months, until the end of July, to leave Spain without any of their gold, silver, money, horses, or arms. Traditionally, people have stated that more than 20,000 Jews left Spain during this time. More recent studies done by Historians have shown that only about 40,000 of the 80,000 Jews left Spain while the other converted to Christianity.

Pope Alexander VI gave Isabella the title of Catholic Monarch. Isabella and Ferdinand had gone through a physical unification of Spain and spiritual unification as they tried to convert their country and subjects into Roman Catholicism. The Treaty of Granada was broke in 1502 following a Muslim uprising in 1499, among other issues. Muslims were ordered to leave Spain or convert to Christianity. Isabella and Ferdinand became consumed with the administration and politics of their newly created empire.

The two of them were concerned with their succession so they worked together to link the Spanish crown to other European rulers. By early 1497, it seemed that all of the pieces to do this were in place. At this point their son John, Prince of Asturias had married Archduchess Margaret of Austria, providing the connection to the Habsburgs. Isabelle, their oldest child and daughter, married Manuel I of Portugal while Joanna married philip of Burgundy, another Habsburg prince. But John died shortly after he married Margaret and Isabella, Princess of Asturias, was in childbirth with her son Miguel, who only lived to be two years old, when she died. Because of this, the crown passed down to her third child, Joanna of Castile, and her husband, Philip of Habsburg. Isabella was able to make successful matches for her three younger daughters. Maria married her older sister’s husband Manuel I of Portugal and Catherine married Arthur, Prince of Wales. Arthur died shortly after and Catherine went on to become Henry VIII of England’s first wife until their marriage was annulled later on.

On September 14, 1504, Isabella withdrew from governmental affairs officially. Not long after, she died on November 26, 1504 while in Medina del Campo. Some people say that she had been in decline since 1497 when her only son, John, died. Queen Isabella was entombed in the Capilla Real, built by her grandson Charles V, Holy Roman Empire (Carlos I of Spain) in Granada. Ferdinand, who continued to rule until his death in 1516 is entombed beside her along with her successor and third child, Joanna, and her husband, and Miguel (the son of Queen Isabella’s daughter, Isabella, who died at two years old. Besides Capilla Real is a museum with Isabella’s crown and scepter.