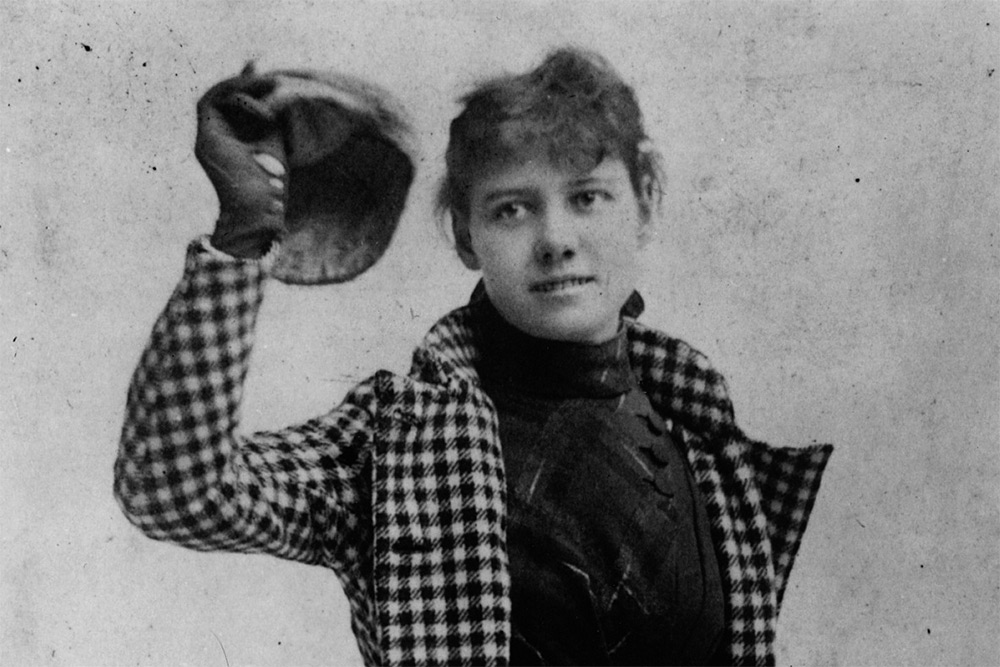

American journalist Elizabeth Jane Cochran Seaman, or “Nellie Bly” is famous for breaking records when she traveled around the world in 72 days and for exposing mental institutions. Bly was one of the pioneers in her occupation and through her hard work, launched an entirely new form of investigative journalism.

On May 5, 1864, Elizabeth Jane Cochran was born in Cochran’s Mills (now a suburb in Pittsburgh) Pennsylvania to laborer and mill worker Michael Cochran and Mary Jane Cochran. Elizabeth, or “Pinky” she was called as a young girl because she often wore the color, was taught by her father on a cogent lesson that dressed the virtues that came from hard work and determination. As a teenager, Cochran wanted to be more sophisticated by changing her name to “Cochrane” and dropping the childhood nickname. While she attended a term at boarding school, she had to drop out because her family did not have enough money to pay the tuition bills.

When Cochrane and her family moved to Pittsburgh, she read a highly misogynistic column in the Pittsburgh Dispatch entitled “What Girls Are Good For”. Under a pseudonym, she wrote a very fierce and fiery response. The newspaper’s editor George Madden was very impressed with the passion in the piece, and put out an ad looking for the author. So, Cochrane introduced herself to Madden, and her offered her to continue writing for the paper under her pseudonym, “Lonely Orphan Girl”. When she published the next piece, Madden was even more impressed and offered her a full time job writing. So, Cochrane adopted the permanent pen name of “Nellie Bly”, inspired by the popular Stephen Foster’s song “Nelly Bly”.

Bly’s early work focused more on working women. She began writing investigative articles on women working in factories. However, those at the Dispatch wanted her to work more on the “women’s pages”, where she would write about fashion, society, and gardening. Bly did not want to, so instead traveled as a foreign correspondent For about half a year, Bly spent her days writing reports on the daily lives and customs of those who lived in Mexico that were later published in her book, Six Months in Mexico. The authorities in Mexico found out about Bly’s reports, especially one about the dictator at the time, and then threatened to have her arrested, so she quickly fled back home to Pittsburgh.

In 1887, Bly made the decision to leave her job at the Pittsburgh Dispatch and move to New York City. However, the next four months were spent for Bly jobless and penniless. Finally, she was able to take on an undercover assignment when she marched into the offices of the New York World, Joseph Pulitzer’s newspaper. Bly agreed to pretend to be insane to be admitted into a mental institute, where she would report the brutal lives of those on blackwell Island at the Women’s Lunatic Asylum.

For nights, Bly practiced making deranged expressions. From there, she checked into a boardinghouse, where she refused to sleep and told the other boarders she was afraid of them because they looked “crazy”. The other boarders decided Bly was the crazy one, so they called the police over the next day and she was taken to a courtroom. Bly feigned amnesia, and the judge came to the conclusion she was drugged. They had many doctors come into examine her, all deciding that she was insane.

Since she had been committed to the hospital, Bly was able to firsthand experience the lives of those who lived there. They ate gruel broth with spoiled meat and bread that was essentially just dried dough. The water was dirty and nearly undrinkable. All the patients considered to be dangerous, were tied together with a rope. For most of the day, all the patients were required to sit on hard benches, hardly protected from the cold outside. Everywhere was covered in waste, especially where they ate, and rats were all over. To bathe the patients, they poured freezing water on their heads and the nurses were abusive and would often beat the patients that did not obey their commands to “shut up”. Bly came to the realization after speaking with many patients, that they, just like her, were not insane.

“What, excepting torture, would produce insanity quicker than this treatment? Here is a class of women sent to be cured. I would like the expert physicians who are condemning me for my action, which has proven their ability, to take a perfectly sane and healthy woman, shut her up and make her sit from 6 a.m. until 8 p.m. on straight-back benches, do not allow her to talk or move during these hours, give her no reading and let her know nothing of the world or its doings, give her bad food and harsh treatment, and see how long it will take to make her insane. Two months would make her a mental and physical wreck.” – Nellie Bly

Ten days went by in the horrid hospital, and the New York World finally had the asylum release Bly. She published a report as a book and titled it Ten Days in a Mad-House. The book was an instant success, exposing the harshness of mental institutes and made her famous very quickly. Physicians and staff were embarrassed, trying to say that Bly had deceived many professionals working at asylums. Even a grand jury launched an investigation and requested for Bly to assist them in it. She had proposed many changes in her report, and the grand jury recommended that mental institutions follow those.

The following year, Bly made a suggestion to her editor that she turn the fiction story of Around the World in Eighty Days into a real story. This would be the first attempt made, fifteen years after the book was published. A year later, Bly boarded the Augusta Victoria, a steamer, on November 14, 1889. The journey she had just embarked on would be 24,899 miles long and take her just under eighty days.

All Bly took with her was the dress she was wearing, an overcoat, underwear, and a small bag with all her toiletries. All of her money was in a bag she kept tied around her neck, mostly British bank notes with some in American.

Meanwhile, Phileas Fogg was attempting to recreate the novel and the newspaper Cosmopolitan sponsored Elizabeth Bisland to do the same. The three raced to complete the journey. To keep people interested in Bly’s story, her newspaper, the New York World, created a “Nellie Bly Guessing Match” for people to estimate how long it would take her. Whoever had the closest guess won a free trip to Europe along with spending money for said trip.

Bly travelled through many countries, including England, France, Brindisi, the Suez Canal, Colombo (or Ceylon), the Straits Settlements of Penang and Singapore, Hong Kong, and finally, Japan. She was able to send progress reports back to New York through telegraphs and the efficient submarine cable networks. The reports were often short, but she was able to send longer ones by way of regular post. So these updates were delayed by several weeks. Her travelling was done on steamships and by train. Though the railroad systems caused setbacks during the last part of the Race in Asia. Some small notable events include her visiting a leper colony in China and the purchasing of a monkey in Singapore.

Due to rough weather on the Pacific as she made her way to San Francisco, she was delayed by two days, arriving on January 21. Pulitzer sent a private train to get her back to New York and she arrived on January 25, 1890, her trip haven taken a world breaking seventy-two days.

Meanwhile, Bisland was not yet done with her trip, arriving four days later. Bly’s world record was later beaten by George Francis Train who made it around in sixty-four days then travelling again in sixty days.

Five years after her trip, Bly married Robert Seaman, a millionaire manufacturer who was seventy-three, while she was only thirty-one. Bly decided to retire from her job as a journalist and served as the Iron Clad Manufacturing Co.’s president. The company made steel containers. Nine years later, Seaman died in 1904 right around the same time the Iron Clad had started manufacturing steel barrels. Some claimed Bly invented the barrel, but it is believed the real inventor was Henry Wehrhahn. Bly did invent a few other things though, including a novel milk can and a stacking garbage can. She was one of the leading female industrialist in the country at the time, but soon Iron Clad went bankrupt from employees embezzling funds. Bly returned to reporting after and wrote stories about what was going on on the Eastern Front in Europe in the Great War. One of her notable stories was on the Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913.

On January 27, 1922, fifty-seven year old Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman died of pneumonia in New York City. She was interred in The Bronx at the Woodlawn Cemetery.