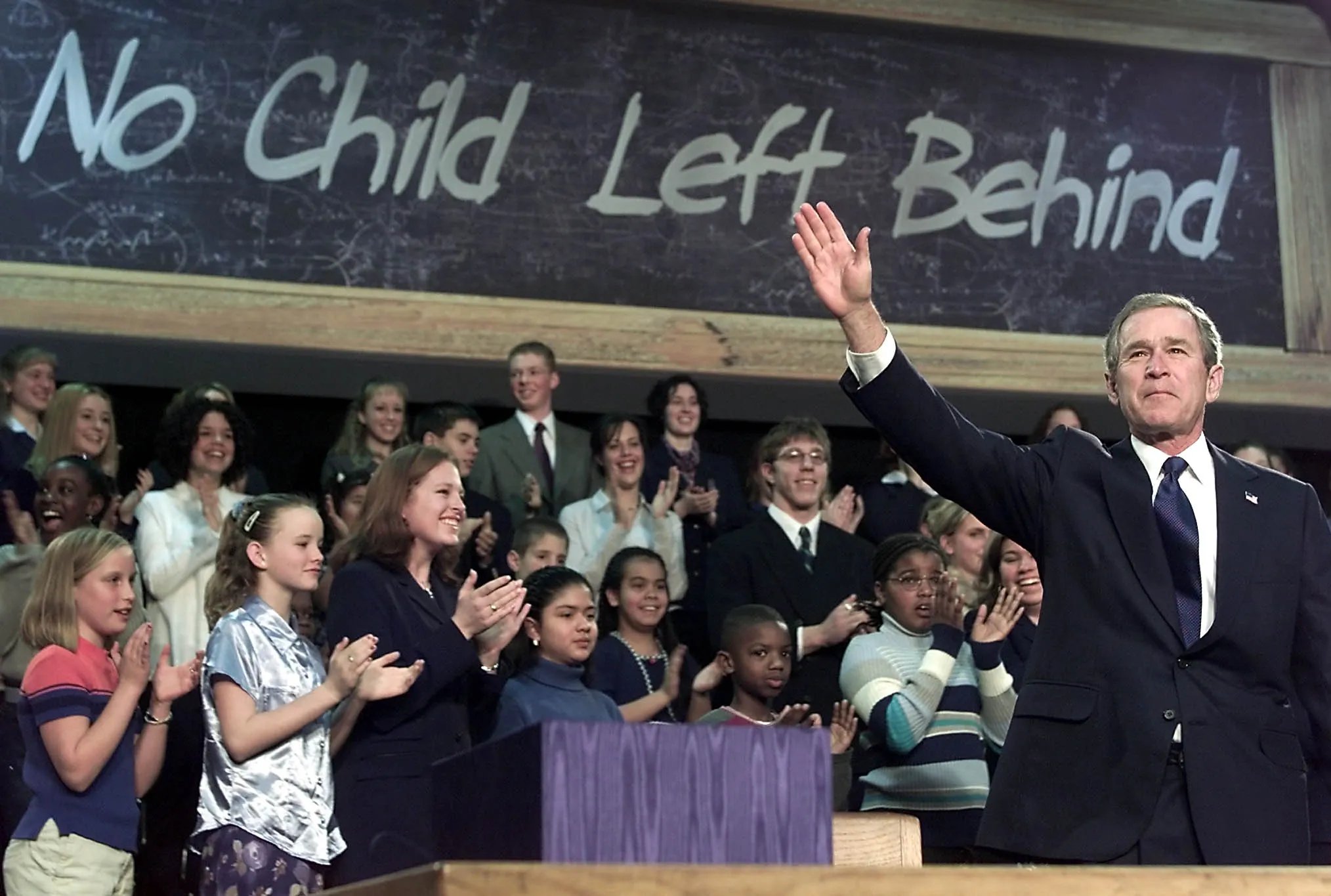

On January 8, 2002, George W. Bush sat at a school desk in Hamilton, Ohio, flanked by Ted Kennedy and John Boehner, and signed a thick stack of papers with a kid-sized flag behind him. The photo looks almost wholesome: a Republican president, a liberal lion of the Senate, and smiling students. The law he signed, the No Child Left Behind Act, was sold as a promise that every child in America would learn to read and do math at grade level.

What actually happened was far messier. No Child Left Behind (NCLB) rewired how the federal government dealt with public schools. It tied money to test scores, pushed states into a high-stakes accountability regime, and helped ignite the modern testing wars. Within a decade, almost everyone, left and right, was angry at it.

No Child Left Behind was a 2002 federal education law that required annual testing, set a goal of 100% proficiency in reading and math, and punished schools that failed to meet targets. It reshaped US education by making standardized testing the main measure of school success.

To understand why that photo-op in Ohio mattered, you have to go back to the 1980s panic over failing schools, the bipartisan politics of the 1990s, and a Republican president who decided his first big domestic win would be about reading scores, not tax cuts.

Why did the US end up with No Child Left Behind?

The roots of NCLB go back to a very different White House. In 1983, Ronald Reagan’s education secretary released a report titled “A Nation at Risk.” It warned that the United States was drowning in “a rising tide of mediocrity” in its schools. The language was apocalyptic. The fear was simple: if American kids could not read, write, and do math as well as kids in Japan or Germany, the US would lose its economic edge.

That report did not change federal law overnight, but it started a drumbeat. Through the 1980s and 1990s, governors and state legislatures experimented with standards and tests. The idea was that states should spell out what students should know and then measure whether schools were teaching it.

George H. W. Bush hosted an education summit with governors in 1989. Bill Clinton, then governor of Arkansas, was there. Both parties started talking about “standards” and “accountability.” The federal government, which had mostly focused on funding poor districts and enforcing civil rights, began to flirt with the idea of demanding results.

By the late 1990s, two things were clear. First, test scores showed big gaps between white students and Black and Latino students, and between rich and poor districts. Second, the 1965 Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), the main federal education law, had been reauthorized several times but without a strong teeth-baring accountability system.

In other words, Washington was sending money to schools, but there was no serious federal pressure to prove that kids were learning. That gap between money and measurable results set the stage for a law that would try to force schools to show progress on paper.

This mattered because it created the political space for a president to argue that the federal government should no longer just write checks to schools, it should demand proof that children were actually learning.

How did George W. Bush turn Texas ideas into national law?

When George W. Bush ran for president in 2000, he did not just talk about tax cuts and foreign policy. He ran as a “compassionate conservative” and made education his main domestic issue. As governor of Texas, he had pushed a tough accountability system: annual tests, public reporting of scores, and consequences for schools that did not improve.

Texas officials claimed big gains, especially for Black and Latino students. Later research would question some of those claims and point to test prep and dropout issues, but at the time, the “Texas miracle” was a political selling point. Bush argued that Republicans could care about poor kids too, just in a different way than Democrats. His phrase was “the soft bigotry of low expectations.”

Once in office, Bush moved fast. He wanted a major education bill in his first year. He also needed Democrats to pass anything that looked like a national testing system. So his team worked with Senator Ted Kennedy and Representative George Miller, two of the most powerful Democrats on education.

The deal that emerged in 2001 was classic Washington horse-trading. Republicans got strong accountability, annual testing, and consequences for schools. Democrats got more federal money for poor districts and language about closing achievement gaps.

Then came September 11, 2001. After the attacks, Bush’s approval ratings soared. Congress and the White House were suddenly focused on terrorism and war. Yet education reform, already in motion, kept moving. In that atmosphere of unity and deference to the president, NCLB passed with huge bipartisan majorities.

When Bush signed the bill in January 2002, surrounded by both Republicans and Democrats, it looked like a rare moment of national agreement. The Texas model had gone national, with the full weight of the federal government behind it.

This mattered because it locked in a bipartisan consensus that the way to fix schools was to measure them constantly and punish failure, a consensus that would be hard to unwind even after the politics shifted.

What exactly did No Child Left Behind require?

No Child Left Behind was not just a slogan. It rewrote the rules of the main federal education law, ESEA, in very specific ways.

First, it required states to test students in reading and math every year from grades 3 through 8, and once in high school. States had to use those test results to measure school performance and report them publicly, broken down by race, income, disability status, and English-learner status.

Second, it set a bold, some would say impossible, goal: 100 percent of students would be “proficient” in reading and math by the 2013–2014 school year. Each state could define “proficient,” but they had to set a trajectory of rising targets. This system was called Adequate Yearly Progress, or AYP.

If a school receiving federal Title I funds (money for high-poverty schools) failed to make AYP for two years in a row, it was labeled “in need of improvement.” That label triggered a sequence of escalating consequences: students could transfer to a better public school, the district had to offer free tutoring, and if the school kept missing targets, it could face staff changes, restructuring, or even conversion to a charter school.

NCLB also required that teachers in core subjects be “highly qualified,” which usually meant having a degree and certification in the subject they taught. It pushed states to use “scientifically based” reading instruction, a phrase that would fuel fierce debates over phonics and reading curricula.

One key misconception: NCLB did not create the federal Department of Education, nor did it give Washington control over curriculum. States still decided what to teach. The law controlled how schools were measured and how they were punished or rewarded, not the specific content of lessons.

No Child Left Behind was a 2002 federal law that tied federal school funding to state test scores and required every state to test students annually in reading and math. It made standardized test results the main yardstick for judging schools.

This mattered because it shifted the center of gravity in American education from local control and professional judgment toward data, targets, and federal pressure, changing how schools operated day to day.

How did No Child Left Behind change classrooms and school behavior?

On paper, NCLB was about accountability and equity. In classrooms, it often felt like a test prep regime. Teachers in many districts saw their schedules reorganized around reading and math blocks. Subjects that were not tested, like social studies, art, and sometimes science in lower grades, got squeezed.

Schools poured time and money into test preparation. Practice tests, data meetings, and “benchmark” assessments became routine. In some places, teachers were told to post test score goals on classroom walls or analyze spreadsheets of scores every week.

There were some clear effects. National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) scores in math for younger students rose in the early 2000s, and some achievement gaps narrowed, especially in the first years of NCLB. Supporters argued that the pressure worked, especially for students who had been ignored.

But the costs were real. The phrase “teaching to the test” became a complaint heard in nearly every district. Many teachers felt their professional judgment was being replaced by scripted curricula designed to boost scores. The law’s demand that every subgroup hit the same targets meant that a school could be labeled failing even if most students were doing well but one subgroup lagged.

In high-pressure environments, some districts crossed ethical lines. The most notorious case was the Atlanta cheating scandal, where educators were convicted of altering test answers. Other districts quietly pushed low-performing students out or steered them away from tested grades.

Parents began to notice that their children’s school experience was changing. For some, especially in communities where schools had long failed to teach basic skills, the focus on reading and math was welcome. For others, especially in more affluent areas, NCLB felt like a blunt instrument flattening education into bubble sheets.

This mattered because it reshaped what schooling looked like for millions of children, narrowing the curriculum in many places and tying the daily work of teachers to a single set of test scores.

Why did No Child Left Behind become so unpopular?

At first, NCLB had broad support. By the late 2000s, it was one of the most disliked federal laws in education history. The reasons came from both left and right, but they converged on the same basic complaint: the law was unrealistic and rigid.

The 100 percent proficiency goal proved to be a political time bomb. As 2014 approached, more and more schools were labeled as failing. Even high-performing suburban schools started missing AYP because one subgroup did not hit the target. States responded by lowering the bar for “proficient” or finding statistical workarounds, but the basic math did not change. You cannot have every school above average.

Teachers’ unions attacked the law for punishing schools without fixing deeper issues like poverty and funding inequality. Civil rights groups were split. Some liked the focus on achievement gaps and data. Others argued that the sanctions fell hardest on schools serving Black, Latino, and poor students, without giving them the resources to improve.

Conservatives grew angry about federal intrusion into what they saw as a state and local responsibility. They did not like Washington dictating how often to test and how to rate schools. Some Republicans who had voted for NCLB began to distance themselves from it.

By the time Barack Obama took office in 2009, Congress was stuck. Nobody wanted to defend NCLB as written, but rewriting it was politically hard. So the Obama administration used waivers. States could escape some of NCLB’s harshest rules if they adopted certain reforms, including college- and career-ready standards and teacher evaluations tied to test scores.

This waiver system kept the basic test-based accountability structure alive while layering on new pressures. It also fed the perception that the federal government was micromanaging schools, now through the executive branch instead of Congress.

This mattered because the backlash against NCLB and its waivers set the stage for the next big rewrite of federal education law, one that would try to keep accountability while loosening Washington’s grip.

What replaced No Child Left Behind, and what is its legacy?

After years of stalemate, Congress finally acted. In 2015, it passed the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), which President Obama signed in December. ESSA kept the basic structure of ESEA and some of NCLB’s ideas but changed who held the power.

Under ESSA, states still have to test students in reading and math in the same grades and report results by subgroup. They still have to identify low-performing schools and do something about them. But the 100 percent proficiency goal is gone. AYP is gone. States have much more freedom to design their accountability systems and decide how to weigh test scores versus other factors, like graduation rates or school climate.

In other words, ESSA dialed back the federal micromanagement that made NCLB so toxic while keeping the basic idea that schools should be held responsible for student outcomes.

Yet NCLB’s shadow is long. It normalized the idea that standardized tests are the primary measure of school quality. It trained a generation of educators and administrators to think in terms of data, subgroups, and targets. It also fed a national “opt-out” movement of parents refusing to let their children take state tests.

Many of the debates that rage today, from fights over state tests to arguments about how to measure achievement gaps, grew out of the NCLB era. Even people who have never heard the phrase “Adequate Yearly Progress” are living with its aftereffects when their child’s school sends home test score reports and school ratings.

This mattered because NCLB did not just come and go as a Bush-era project. It reset expectations about what the federal government could demand from schools and what evidence the public should expect about how well children are learning.

Why that 2002 signing photo still matters

The Reddit image of George W. Bush signing No Child Left Behind captures a rare moment: a Republican president, a Democratic senator, and a cheering crowd all agreeing that Washington should get tougher on schools. It is easy, two decades later, to forget how much hope was packed into that ceremony.

Supporters thought they were ending decades of complacency about poor children and racial gaps. Critics warned that you cannot test your way to equity. Both were partly right. The law did expose ugly disparities and force them into the open. It also pushed schools into a narrow, high-pressure model that many educators and families came to resent.

Today, when people argue about whether there is “too much testing” or whether school ratings are fair, they are arguing inside a world that NCLB helped build. The 2002 signing did not just tweak a federal department. It marked the moment when the United States decided that the main way to judge its public schools would be through a battery of standardized tests and a spreadsheet of scores.

That is why the photo matters. It is not just a snapshot of a law being signed. It is a snapshot of a bet that data, pressure, and punishment could fix American education, a bet the country is still trying to sort out.

Frequently Asked Questions

What was the main purpose of No Child Left Behind?

The main purpose of No Child Left Behind was to raise student achievement and close gaps between different groups of students by requiring annual testing in reading and math, publicly reporting scores by subgroup, and imposing consequences on schools that did not make progress. It tried to tie federal funding to measurable academic results rather than just enrollment or need.

Did No Child Left Behind improve test scores?

In the early years after No Child Left Behind passed, national math scores for younger students rose and some achievement gaps narrowed, especially on the National Assessment of Educational Progress. Over time, gains slowed and many educators argued that the focus on test scores came at the expense of a broader education. Researchers still debate how much of the early improvement was caused directly by NCLB.

Why was No Child Left Behind so controversial?

No Child Left Behind became controversial because it set an unrealistic goal of 100% proficiency, labeled many schools as failing, and tied high-stakes consequences to test scores. Teachers and unions said it narrowed the curriculum and punished schools without addressing poverty or funding. Conservatives disliked the federal intrusion into state and local control. By the late 2000s, criticism was coming from across the political spectrum.

What replaced No Child Left Behind?

The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), signed by President Barack Obama in 2015, replaced No Child Left Behind. ESSA kept the requirement for annual testing and reporting of subgroup performance but gave states much more control over how to design accountability systems and how to intervene in low-performing schools. It ended the 100% proficiency target and the rigid Adequate Yearly Progress system.