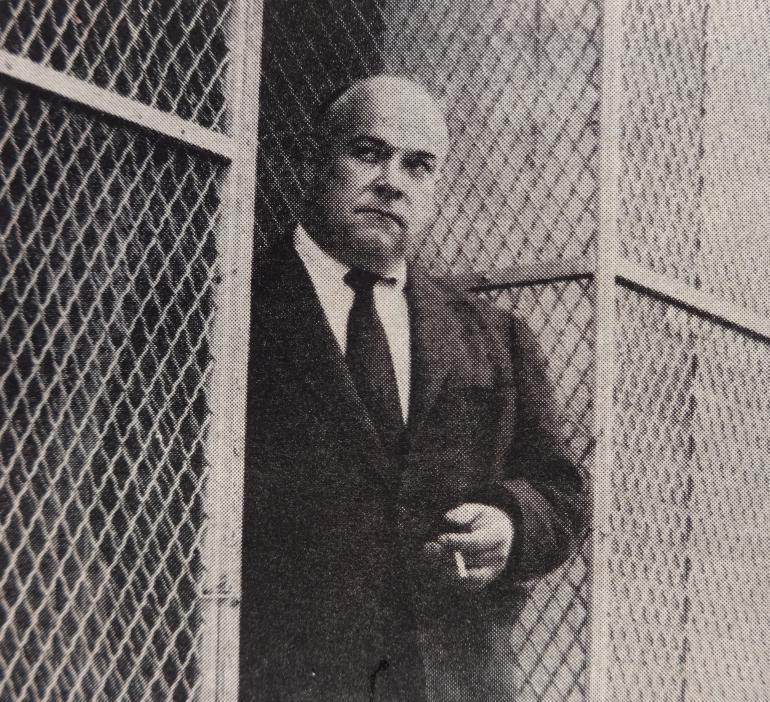

George Hunter White liked to brag about his work. In 1971, the retired narcotics agent and CIA contractor looked back on the 1950s with a kind of glee. Running a CIA safe house for MKULTRA in San Francisco, he wrote that it was “fun, fun, fun. Where else could a red-blooded American boy lie, kill, cheat, steal, rape, & pillage with the sanction & blessing of the All-Highest?”

At almost the same time, on the other side of the country, a very different scandal was about to explode. In 1972, the public learned that the U.S. Public Health Service had spent 40 years watching hundreds of Black men in Alabama suffer and die from syphilis, even after a cure existed. That project is now known as the Tuskegee syphilis study.

They look similar because both MKULTRA and the Tuskegee study were secret government experiments on human beings who did not give informed consent. Both treated people as expendable material in the name of national goals. But they grew out of different fears, used different methods, and left different scars.

By the end of this story, you will see how two notorious programs, one run out of CIA brothels and the other out of Southern clinics, reveal the same core problem: what happens when the state decides that some people’s rights can be quietly suspended.

Why did MKULTRA and Tuskegee begin in the first place?

MKULTRA was born in the Cold War panic of the early 1950s. American officials watched Communist show trials in Eastern Europe and Korea and convinced themselves that the Soviets and Chinese had discovered mind control. The CIA wanted its own tools.

In 1953, CIA director Allen Dulles approved a program under chemist Sidney Gottlieb to research “chemical, biological, and radiological” methods for controlling or breaking a person’s mind. That umbrella project was MKULTRA. It had dozens of subprojects, from LSD dosing to hypnosis. George Hunter White’s brothel operation in San Francisco and New York, code-named Operation Midnight Climax, was just one of them.

The logic was national security. If the enemy could drug and brainwash, the CIA argued, the United States had to get there first. That fear gave cover to experiments that would have been unthinkable in public.

The Tuskegee syphilis study had different roots. It began in 1932, long before the Cold War, as a Public Health Service project in Macon County, Alabama. Officials wanted to observe the “natural history” of untreated syphilis in Black men.

About 600 Black sharecroppers were enrolled. Roughly 399 had syphilis, around 201 did not. They were told they were being treated for “bad blood,” a vague local term. They were not told they had syphilis. They were not told they were part of an experiment. The racial assumptions of the era, including ideas that Black bodies were different and that poor Black men were unlikely to get treatment anyway, helped officials rationalize the study.

In 1943, penicillin became a standard, effective treatment for syphilis. The study did not end. Doctors kept the men in the project and, in many cases, blocked them from getting penicillin elsewhere. The goal had quietly shifted from any hope of treatment to pure observation, no matter the cost to the subjects.

So what? Both programs started because powerful institutions convinced themselves that some larger goal, winning the Cold War or advancing medical knowledge, justified cutting corners on consent and ethics, which set the stage for everything that followed.

How did MKULTRA actually work compared to Tuskegee?

MKULTRA was chaotic by design. Sidney Gottlieb ran it with minimal paperwork and maximum secrecy. Money flowed through front organizations to universities, hospitals, and private researchers who often did not know they were funded by the CIA.

One core method was surreptitious drugging. LSD was the favorite. CIA officials, including Gottlieb, dosed colleagues without warning in office retreats. Outside the agency, they wanted to see how unsuspecting civilians would react.

That is where George Hunter White came in. A veteran narcotics agent with a taste for undercover work, he set up CIA safe houses in San Francisco and New York in the mid‑1950s. They were wired with microphones and two-way mirrors. Sex workers, on the CIA payroll, were told to bring clients there. The women would slip LSD or other substances into drinks. White and other observers watched from behind the glass, taking notes on how the men reacted.

There was no consent. The men thought they were paying for sex. They were actually unwitting test subjects in a classified program. White decorated the safe houses with lurid art and stocked them with liquor, then treated the whole thing as a kind of private playground. His later description of “fun, fun, fun” captures the culture: experimentation mixed with impunity.

MKULTRA also funded experiments in prisons, mental hospitals, and universities, often targeting people with little power to refuse. Doses could be extremely high. In at least one case, a U.S. Army scientist, Frank Olson, died after being secretly dosed with LSD at a CIA retreat in 1953. Whether his death was suicide or something darker is still debated.

The Tuskegee study used quieter methods. There were no brothels or spy gadgets. The violence was slow.

Public Health Service doctors and local Black nurses examined the men, drew blood, and performed painful spinal taps. They called these “special free treatment” to keep the men participating. The men received placebos, vitamins, and aspirin, but not penicillin for syphilis.

Researchers tracked the men’s health over decades. They watched as some went blind, insane, or died from complications of syphilis. They recorded the infection of wives and the birth of children with congenital syphilis. The men were poor, often illiterate, and trusted the doctors who came in government cars.

In both programs, the victims were not told the truth. In MKULTRA, they were often random civilians, prisoners, or psychiatric patients, tricked or coerced into experiments. In Tuskegee, they were a defined group of Black men, carefully recruited and then misled for 40 years.

So what? The methods differed in speed and style, but both programs depended on secrecy, deception, and targeting people with little power, which made abuse not a bug in the system but the system itself.

What happened to the people caught in these experiments?

MKULTRA’s human toll is hard to measure because the CIA destroyed many records in 1973. What we know comes from surviving documents, court cases, and testimony.

Some subjects experienced terrifying trips, psychotic breaks, or long-term psychological damage. Prisoners given high doses of LSD described lasting paranoia and flashbacks. In Canada, a related CIA‑funded project at the Allan Memorial Institute in Montreal used heavy drugs, electroshock, and sensory deprivation on psychiatric patients, leaving some with permanent memory loss.

Frank Olson’s death became the most famous MKULTRA case. After being dosed without consent, he grew anxious and disturbed. Days later, he fell from a New York hotel window. The CIA called it suicide. His family spent decades fighting for answers. When MKULTRA became public in the 1970s, the Olson case helped fuel outrage.

Operation Midnight Climax victims are even harder to trace. They were johns, often married men, who did not report their nights in CIA safe houses. Some likely had terrifying reactions to the drugs. We do not know their names.

The Tuskegee victims are better documented. Of the 399 men with syphilis at the start, many died from the disease or its complications. Their wives and partners were exposed. Some children were born with congenital syphilis, a condition that can cause deformities, blindness, or early death.

By the time the study was exposed, generations had been affected. The men had missed the chance for a cure that had been widely available since the 1940s. They had trusted the government and been betrayed.

In both cases, the people on the receiving end had almost no say. They were not told the risks. They were not given a choice. Their suffering was treated as data.

So what? The outcomes were not just individual tragedies, they were proof that when secrecy and power combine, human beings can be reduced to disposable tools, with damage that ripples through families and communities.

How were MKULTRA and Tuskegee exposed and stopped?

MKULTRA came to light in fragments. In the mid‑1970s, after Watergate, Congress began digging into intelligence abuses. The Church Committee in the Senate and the Rockefeller Commission looked at CIA activities inside the United States.

By then, CIA director Richard Helms had ordered many MKULTRA files destroyed in 1973, as the Watergate scandal grew. Even so, investigators found surviving financial records and memos. Sidney Gottlieb testified in secret. George Hunter White was interviewed. The picture that emerged was disturbing: a sprawling program of drug and mind‑control experiments, often on unwitting subjects.

The public reaction was angry but somewhat muted by the complexity and the missing records. MKULTRA was officially shut down. Some victims or their families received settlements, including the Olson family. New guidelines were announced for CIA activities.

The Tuskegee study blew up more directly. In 1972, a whistleblower, Peter Buxtun, a Public Health Service employee, leaked information to the press after his internal complaints went nowhere. The Associated Press ran the story. The idea that the government had watched Black men die from a treatable disease for decades hit like a bomb.

Congress held hearings. The study was halted. In 1973, a class‑action lawsuit was filed on behalf of the men and their families. The government settled in 1974, agreeing to pay millions in damages and provide lifetime medical care to survivors, their wives, widows, and children.

In 1997, President Bill Clinton formally apologized on behalf of the United States. Some survivors sat in the White House as he spoke. The apology came 25 years after the scandal broke and 65 years after the study began.

So what? Exposure ended both programs, but in different ways: MKULTRA faded out through partial revelations and destroyed files, while Tuskegee exploded into a national scandal that forced public reckoning and direct government apology.

What legacies did MKULTRA and Tuskegee leave behind?

MKULTRA’s legacy is tangled up with public distrust of intelligence agencies. When people talk about “CIA mind control,” they are not just repeating conspiracy theories. There really was a CIA program that experimented with drugs, hypnosis, and sensory deprivation on unwitting people.

Legally, MKULTRA helped push reforms on how intelligence agencies operate inside the United States. The Church Committee’s work led to new oversight mechanisms and executive orders limiting experiments on human subjects. It also fed a broader sense that secret agencies, left unchecked, will cross ethical lines.

MKULTRA also left a cultural mark. It appears in movies, novels, and music as shorthand for government overreach. The lack of full documentation keeps it alive in the imagination. The destroyed files mean we will probably never know the full scope of what happened.

The Tuskegee study’s legacy is more direct and measurable in public health. The scandal helped drive the creation of modern research ethics in the United States.

In 1974, Congress passed the National Research Act, which set up institutional review boards (IRBs) to oversee research involving human subjects. The Belmont Report in 1979 laid out three core principles: respect for persons, beneficence, and justice. In plain terms, that means informed consent, minimizing harm, and not dumping risks on vulnerable groups.

Today, when you sign a consent form for a medical study, Tuskegee is part of the reason that form exists.

The study also left deep scars in Black communities. Surveys and studies have found lasting distrust of medical institutions among African Americans, and Tuskegee is often cited as a reason. During the COVID‑19 pandemic, public health officials had to address Tuskegee directly when talking about vaccines.

So what? MKULTRA reshaped how Americans think about secret intelligence and abuse of power, while Tuskegee reshaped the rules of medical research and left a lasting wound in Black Americans’ relationship with the health system.

So were MKULTRA and Tuskegee the same kind of crime?

They look similar because both MKULTRA and the Tuskegee syphilis study were secret U.S. government experiments that violated informed consent and harmed people. In both, officials convinced themselves that some higher mission justified using human beings as means to an end.

But the differences matter.

MKULTRA was driven by Cold War fears and run by the CIA. Its victims were varied: soldiers, prisoners, psychiatric patients, random civilians in brothels. The abuse was often fast and chaotic, with drugs and psychological shocks. The program was short‑lived, roughly from 1953 to the early 1960s, and then partially buried.

Tuskegee was driven by racism and a skewed idea of medical science. It targeted a specific, already marginalized group: poor Black men in the rural South. The harm unfolded slowly, over 40 years, as doctors watched disease progress and blocked treatment. It was not a rogue operation. It was run by the Public Health Service, with cooperation from local institutions, and published in medical journals without much objection until the scandal broke.

One more difference: MKULTRA has fed a culture of suspicion about what else the government might be hiding. Tuskegee has fed a very specific, justified suspicion among Black Americans that their bodies and lives are not valued equally in medicine.

So what? Putting MKULTRA and Tuskegee side by side shows that abuses of human subjects are not accidents of one agency or one era, they are recurring risks whenever secrecy, fear, and prejudice outweigh the basic idea that people have a right to know what is being done to them.

Frequently Asked Questions

What was Operation Midnight Climax in MKULTRA?

Operation Midnight Climax was a CIA subproject of MKULTRA in the 1950s. George Hunter White ran CIA safe houses in San Francisco and New York that were set up as brothels. Sex workers, paid by the CIA, brought clients to these locations, where the men were secretly given LSD or other drugs. CIA observers watched from behind two-way mirrors to see how unsuspecting civilians reacted to the substances.

What was the Tuskegee syphilis study and what did it do?

The Tuskegee syphilis study was a U.S. Public Health Service project that ran from 1932 to 1972 in Macon County, Alabama. About 600 Black men, most of them poor sharecroppers, were enrolled. Roughly 399 had syphilis, but they were told they were being treated for “bad blood.” Even after penicillin became a standard cure in the 1940s, doctors did not treat the men’s syphilis, instead observing the long-term effects of the untreated disease. Many men died or suffered serious complications, and their families were affected as well.

How did MKULTRA and the Tuskegee study change research ethics?

Both scandals pushed the United States to tighten rules on human experimentation. MKULTRA helped spur congressional investigations into intelligence abuses and led to new oversight of CIA activities. The Tuskegee study had a more direct impact on medical research. It led to the National Research Act of 1974, the creation of institutional review boards (IRBs), and the Belmont Report, which set out principles like informed consent, minimizing harm, and fair selection of research subjects.

Did the U.S. government ever apologize for these experiments?

For Tuskegee, yes. In 1997, President Bill Clinton issued a formal apology on behalf of the U.S. government to the survivors and families of the men in the study. They also received financial settlements and lifetime medical care as part of a 1974 legal settlement. For MKULTRA, there was no single formal presidential apology, but some victims or their families received compensation through lawsuits or settlements after congressional investigations exposed parts of the program in the 1970s.