Louisa May Alcott is known for her famous classic Little Women, published in 1868. She wrote two sequels to the book as well. Throughout her life, her family went through financial problems, so Louisa began working at a young age to support her family. Not only was Alcott a prominent author, but she was also a well known abolitionist and women’s rights activist. During the civil war, Alcott worked as a nurse, shortly before Little Women was published, becoming a successful, full time author. Due to health problems in her later years, Alcott died in 1888.

On November 29, 1832, Louisa May Alcott was born to Amos Bronson Alcott, an educator and transcendentalist who was also born that very day in 1799, and Abby May, a social worker, in Germantown, Pennsylvania. Anna Bronson Alcott was Louisa’s older sister by two years, then her sister Elizabeth Sewall Alcott was two and a half years her junior, and Abigail May Alcott seven years. Louisa Alcott’s future novel, Little Women, was based off her and her three sisters.

The family moved to Boston in 1834 when their father opened an experimental school. Alongside famous poet Ralph Waldo Emerson and leading transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau, Amos Bronson Alcott joined the Transcendental Club. Bronson Alcott shaped his daughter’s perfectionist views, as well. However, he often conflicted with his wife and daughters because he was unable to provide for the family. Not only that, but Bronson Alcott often showed attitude towards Louisa Alcott’s wind and independent personality.

Once again, the family moved to a cottage in Concord, Massachusetts alongside Sudbury River in 1840. Bronson Alcott had faced many setbacks with his school, so they left Boston. For three years, they lived in the cottage, having described it as “idyllic”, peaceful and happy. But Alcott and her family moved in 1843 to the Utopian Fruitlands in Massachusetts. The Fruitlands had been established by both Bronson Alcott and Charles Lane, though it collapsed and they moved in 1844. This time, the Alcotts rented rooms before purchasing a home in Concord they called “Hillside” in 1845. Without Abby May Alcott’s inheritance, the purchase would not have been possible.

While most of her education came from her strict father, Louisa Alcott also had lessons from Henry David Thoreau. other family friends and well known authors of the time such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Margaret Fuller, and Nathaniel Hawthorne gave the future novelist instruction as well.

At an early age, Alcott began working due to her family’s poor living conditions in poverty. She spent time working as a teacher, seamstress, governess, domestic helper, and writer. Alcott’s two sisters, with the exception of young May, also worked to provide for their family as seamstresses. Their mother began working as a social worker with Irish immigrants. With all the pressure put on her for supporting her family through various jobs, Alcott found herself going to writing as both a creative and emotional outlet. A series of stories called Flower Fables was published in December of 1849 by seventeen year old Louisa May Alcott. The stories were originally written six years previously intended towards Ralph Waldo Emerson’s daughter Ellen Emerson.

For a week, the Alcott’s hosted a fugitive slave passing through the Underground Railroad. Louisa Alcott read the “Declaration of Sentiments” from the Seneca Falls Convention, the first women’s rights convention. She greatly admired the declaration and advocated greatly for women’s suffrage. Alcott was the first woman in Concord, Massachusetts to register to vote for a school board election. But the Alcott family suffered many more hardships through the 1850s, which was proving to be hard times for them. Louisa Alcott even contemplated suicide when she was unable to find any work in 1857. She was able to find many parallels between her life and Charlotte Brontë when she read Elizabeth Gaskell’s biography of the English author. During 1858, Alcott suffered through the death of her younger sister Elizabeth (later becoming the basis for one of her Little Women characters). Her older sister Anna got married that same year to John Pratt. To Louisa though, she felt that this was the breaking point of the close relationship she had with her sisters.

Alcott worked towards women’s suffrage and abolitionism in her adult years. She wrote for the Atlantic Monthly, a magazine in Boston now known as simply The Atlantic, in 1860. The American Civil War broke out 1861. Alcott served in a Union hospital located in Georgetown, a neighborhood in Washington, D.C. in 1862. Originally intending to serve for three months, Alcott only served at the hospital for six weeks between 1862-63. She had come in contact with typhoid fever, making her horribly ill and close to death, so she had to leave the hospital. Luckily, Alcott was able to recover from being ill.

Letters Alcott sent home were then revised and published in the Commonwealth, an anti-slavery paper in Boston. They were published alongside for sketches based on the letters called Hospital Sketches in 1863. These letters came with Alcott’s first recognitions critically because of observations mixed with her humor. Alcott spoke of the hospitals being mismanaged and indifferent surgeons in her writings. The following year, Moods, a promising novel, was published in 1864.

Under pseudonym A. M. Barnard, Alcott began writing passionate and fiery novels through the mid-1860s. A Long Fatal Love Chase was written in 1866 after she toured Europe and another one of her well known novels of the time was Pauline’s Passion and Punishment. Both protagonists in her novels showed willful, relentless personalities as they searched for what they were trying to find while enacting revenge on those humiliating them. Alcott wrote for children as well. These books had a much more positive reception, leading Alcott to stray from adult books and write more so for children. She did write more adult pieces though, such as a novelette called A Modern Mephistopheles in 1875 and Work in 1873, which was partially an autobiography. Some even suspected the former had been written by Julian Hawthorne, as it was published anonymously.

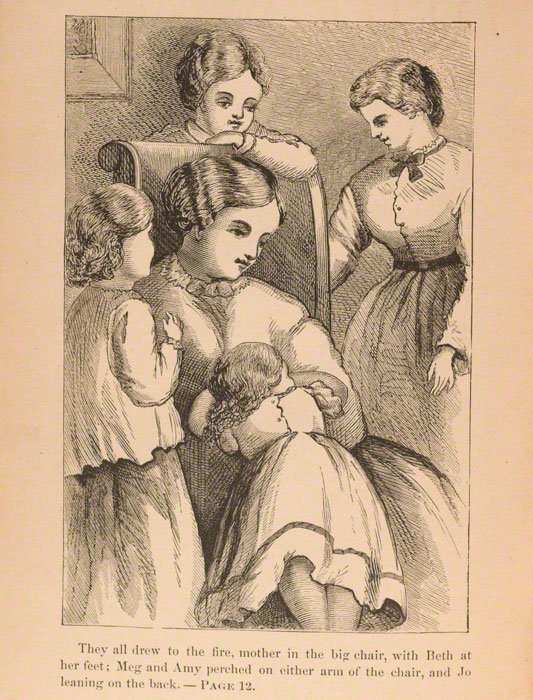

Though she had been successful before, she became even more so when the first part of Little Women (then titled Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy) was published in 1868. This book, though fictional, was partially an autobiography as it recounted the story of four sisters that went through similar events in their lives as Alcott and her sister. The second part, known as Part Second and Good Wives, was published the following year in 1869. While the first part was about the sisters during their teenage years, the second part told their stories of reaching adulthood and getting married.

In 1871, Little Men was published. This sequel to Little Women was about Jo March’s later life with her husband and children at the Plumfield Estate School. The unofficial trilogy was completed with the publication of Jo’s Boys 1886. This book was more so a sequel to Little Men about Jo’s sons and the other Plumfield boys once they reach adulthood.

The four sisters in Little Women were all based upon the four Alcott sisters. Heroine Josephine “Jo” March was based on Louisa Alcott herself. While Alcott remained unmarried, Jo was married by the end of the book. “I am more than half-persuaded that I am a man’s soul put by some freak of nature into a woman’s body … because I have fallen in love with so many pretty girls and never once the least bit with any man,” Alcott had once said. During her tour through Europe, Alcott had met a young man named Ladislas “Laddie” Wisniewski from Poland. Evidence shows that the two most likely had a romantic relationship. “Laddie” had been mentioned in her journals, but before her death, Alcott had deleted any mention of him. She had, however, said that Laddie provided basis for Little Women character Laurie. Every character in the novel though seems to parallel people Alcott had known throughout her life. Louisa’s second youngest sister Elizabeth “Lizzie” died during their teen years while fictional Elizabeth “Beth” died around the same time as well. Alcott had always felt a rivalry of sorts with her youngest sister May, which was mirrored in the book with Jo and Amy’s rivalry. And though she never married, Alcott did eventually take in May’s daughter “Lulu” when her sister passed away in 1879 from childbed fever. She took care of Lulu as if she were her own until she died in 1888.

Alcott’s novel was well received critically and became popular with audiences of all ages.

Alongside other authors such as Anne Moncure Crane, Rebecca Harding Davis, and Elizabeth Stoddard, among others, Alcott joined a group of female authors from the Gilded Age (the 1870s till around 1900 in U.S. history). The group made sure to constantly address women’s rights issues during the time in a more modern and candid manner than most.

In her later years, Alcott suffered through chronic health problems such as vertigo. Both she and some of her earlier biographers credit the illness, and her later death, to mercury poisoning. In the early 1860s when Alcott had come in contact with typhoid fever, they had treated her with a compound that contained mercury. But recent analysis shows that her chronic health may have come from autoimmune disease instead of mercury.

Fifty-five year old Louisa May Alcott died on March 6, 1888 of a stroke. Only two days prior, her father Amos Bronson Alcott had passed away. She is buried on “Authors’ Ridge”, a hillside in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord, Massachusetts. Today, Alcott is remembered for her novel, Little Women, which continues to be a classic piece of literature read around the world.