Lafayette, now imprisoned by the Austrians, was kept in Nivelles, now a municipality in Belgium. Along with a few other men and Jean-Xavier Bureau de Pusy, Lafayette was soon transferred to a prison in Luxembourg. Because of the roles the four men played in the Revolution, they were declared prisoners of state by a coalition military tribunal. Until a new French king was restored to decide what to do with them, they would be kept imprisoned. Then, Lafayette and the three others were put under custody of the Prussians on September 12, 1792. They traveled from Luxembourg to Wesel, a fortress city in Prussia. Between September 19-December 22, 1792, each of the men were kept in the central citadel in their own prison cells. But when Rhineland became threatened by victorious French troops, King Frederick William II had the prisoners moved to the Magdeburg citadel. For a year, they remained in Magdeburg, from January 4, 1793 to January 4, 1794.

Frederick William turned his state prisoners over to the Habsburg Austrian monarch Francis II when he realized that he had very little to gain as the French continued to win in battle. Originally, Lafayette was kept to Neisse, which is located in the region of Silesia. Today, Neisse is known as Nysa, Poland. With his men, Lafayette was taken across the border in Austria on May 17, 1794. There, they were met with a military unit awaiting their arrival. Once a college of the Jesuits, they were delivered to a barracks prison in Olmütz, Moravia (now known as Olomouc, Czech Republic), a fortress city. Lafayette, upon his arrival, attempted using his United States citizenship and contacted the United States minister in The Hague, William Short, to try and secure his release. Though Short, along with other U.S. envoys, wished they could secure his release, his French status would make it impossible, even with United States citizenship. Lafayette’s close friend he met during the American Revolution, George Washington, who was now president had made it very clear to his envoys that the US. did not want to get caught up in European affairs, nor did they have diplomatic relationships with the countries Lafayette was being held prisoner in: Austria and Prussia. Washington did, however, send money to both Lafayette and his wife. Thomas Jefferson, who was now Secretary of State, also found a loophole to provide money and interest to Lafayette because of his time as major general in the American Revolution. Congress rushed this act through and it was signed by Washington shortly after. From then on, Lafayette was able to have more privileges than before while still in prison.

At the time, Lafayette’s wife, Adrienne de La Fayette, had been under house arrest at the Chavaniac, the Lafayette estate, since September 10, 1792. During May of 1794, she had been transferred to La Force Prison in Paris. Many of her relatives were guillotined on July 22, 1794 as well, her mother, sister, and grandmother.Shortly after, Adrienne was moved to the Colléfe du Plessis prison. Afte that she was transferred to a house on rue des Amandiers and then another, rue Notre-Dame des Champs, or the Desnos House. Finally, Adrienne was released on January 22, 1795 all thanks to James and Elizabeth Monroe and Gouverneur Morris. Their son Georges Washington was soon sent to America in April of 1795. While in America, he studied at Harvard and lived with George Washington, his namesake.

Angelica Schuyler Church, Lafayette’s close friend Alexander Hamilton’s sister-in-law, and John Barker Church, who had served in the Continental Army and was now a British Member of Parliament, attempted to aid Lafayette in escaping prison. Justus Erich Bollmann, a young physician from Hanover, was hired as an agent by the Churches. His assistant, Francis Kinloch Huger, was a medical student from South Carolina and the son of Lafayettes first American friend, Benjamin Huger. Lafayette nearly made it out completely during the escape attempt. On an escorted carriage drive outside of Olmütz, Lafayette was able to escape but was recaptured when he became lost.

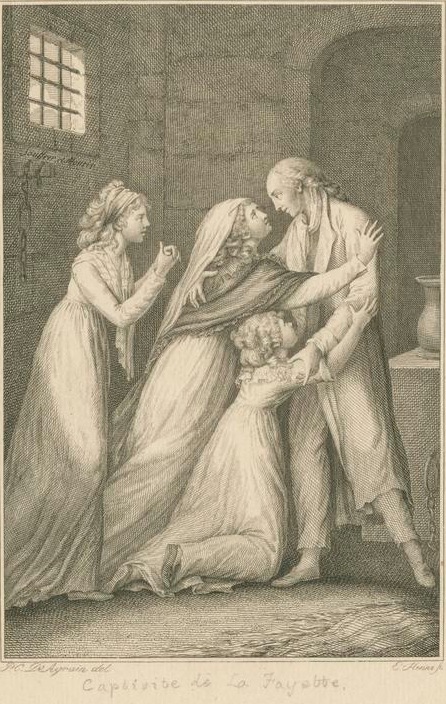

Around the same time, Adrienne had just been released from prison. James Monroe, the U.S. Minister to France, assisted her and their daughters in obtaining Connecticut, which earlier had given the Lafayette family citizenship, passports. Along with their daughters Anastasie and Virginie, Adrienne traveled to Vienna, Austria. There, Adrienne had an audience with Emperor Francis, in hopes of being able to see her husband again. The Emperor granted her and their daughters permission to join Lafayette in captivity after he had spent a year of solitary confinement. On October 15, 1795 the marquis was surprised when his prison door was finally opened, and when his wife and daughters were ushered in by the soldiers. For two years, the family stayed in captivity together.

It was no secret that Lafayette had sympathizers in both Europe and America. They made their influence known through diplomacy, personal appeals, and the press, especially after the Reign of Terror ended in France. The victorious Napoleon Bonaparte , as a result of the Treaty of Campo Formio signed on October 18, 1797, was able to negotiate Lafayette and other state prisoners’ being held at Olmütz release. Under Austrian escort, Lafayette, along with his family, finally left Olmütz on September 19, 1797 after spending over five years in prison. Together they crossed over the Bohemian-Saxonian border. On October 4, 1797, they arrived in Hamburg and were then turned over to American consuk. Finally, the Lafayette family was free!

Lafayette sent a thankful note to General Napoleon Bonaparte for securing his release while still in Hamburg. The French Directorate, the new government in France, refused to allow Lafayette and his family to return if they did not swear his allegiance to the new government. Lafayette did refuse though, believing that the new government was unconstitutional in terms of how it came together. He was left a pauper when the government sold his properties out of spite and revenge. Georges Washington returned from America shortly after and the family spent their time at Adrienne’s aunt’s property close to Hamburg. Lafayette had been hoping to return back to America, but conflict between the U.S. and France had arisen, preventing him from traveling back.

Adrienne left for Paris around November in hopes of securing patrician for her husband. Bonaparte had recently returned back with more french victories, so Adrienne made sure to flatter him graciously. Under the name of “Motier”, Lafayette slipped into France after Bonaparte November 9, 1779’s coip d’état of 18 Brumaire. Confusion in the country was caused by the new regime change, giving Lafayette the perfect chance to sneak in. Adrienne convinced Bonaparte that Lafayette would pledge his support to the new French government and take up residence at the Château de la Grange-Bléneau, where he would retreat from politics and private life, after Bonaparte had become outraged with Lafayette’s return. Lafayette was able to remain in France under the country’s new ruler. The original compromise was that he would be arrested if engaging in politics and his citizenship was taken away. With his family, the marquis took up quiet life at La Grange. He was not even invited to a memorial service in Paris after George Washington’s death in December 1799 that Bonaparte had held and planned. Lafayette had been a very close friend to Washington, so that he was not invited perhaps showed that he really was excluded from public life and politics from then on.

On March 1, 1800, Lafayette’s citizenship was finally restored by Bonaparte, allowing him to recover some of the property he had lost a few years prior. He refused to become the French minister to the United States when Bonaparte offered. Lafayette had firmly decided that he wanted nothing of the sorts to do with Napoleon Bonaparte’s rule and government. He also took part of the small minority that voted against the referendum making Bonaparte the forever consul until his death in 1802. Bonaparte attempted to offer Lafayette a Senate seat and to give him the Legion of honor, both of while Lafayette refused. If it were coming from a democratic government though, Lafayette told Bonaparte, he would have happily taken the honors.

Bonaparte officially became crowned Emperor Napoleon in 1804. He stayed quiet for quite some time, making a Bastille Day address. Thomas Jefferson, who at the time has been president since 1800, offered Lafayette a governorship following the Louisiana Purchase, which Lafayette also declined. He told Jefferson that he had to decline for both personal reasons and the desire to work in France for liberty.

While on a trip to Auvergne in 1807, Adrienne became terribly ill. Complications in her health had begun to arise after spending time in prison. Luckily, she was able to recover on Christmas Eve after becoming seriously delirious. On Christmas Eve she gathered the whole family around her bed, telling Lafayette (in French), that she was all his. After suffering through stomach pains, blisters, abscesses, and sores, she passed away on December 24, 1807. June K. Burton wrote in Two “Better Halves” in the Worst of Times — Adrienne Noailles Lafayette (1759-1807) and Fanny Burney d’Arblay (1752-1840) as Medical and Surgical Patients under the First Empire that most likely lead poisoning was the main cause to her death and illness. Adrienne was so buried in Paris at the Picpus cemetery.

Lafayette had been very much in love with his wife from the time they got married many years before. He spent the following few years at La Grange quietly. Napoleon was only becoming increasingly powerful, not just in France, but all of Europe. At La Grange, Lafayette received many visitors, mainly Americans. Him and Jefferson wrote many letters to each other. Like Lafayette had once done with Washington, him and Jefferson also exchanged gifts through their letters.

The French monarchy was restored when the initial opposing coalition of Napoleon invaded France in 1814. Brother of Louis XVI, Louis XVIII, the comte de Provence, became king. Louis XVIII received Lafayette not long after. Lafayette, being very republican, was in opposition of the Chamber of Deputies, giving only one vote to 90,000 men. He remained at La Grange instead of standing for election that year. Napoleon requested Lafayette serve in his new government after taking Paris in March of 1815, which made the king flee Paris to Ghent. Of course, Lafayette refused the offer. He did, however, accept his election onto the Chamber of Representatives, which was under the Charter of 1815. When Napoleon was defeated at the Battle of Waterloo on June 18, 1815, Lafayette called that Napoleon abdicated, which he did four days later on June 22. Prevented by the British, Lafayette tried to arrange for Napoleon’s passage to America. The former emperor was exiled to the island of Saint Helena where he stayed from October 1815 until his death on May 5, 1821. Lafayette was shortly after appointed a peace commission in the Chamber of Representatives. As the Prussians occupied La Grange and the allies were occupying France, his commision was ignored. In late 1815, the Prussians left and Lafayette took back residence at La Grange as a private citizen.

Both his homes in Paris and La Grange were kept open to Americans that wished to meet Lafayette, though it was not just open to Americans. Sydney, Lady Morgan, a novelist from Ireland, stayed at La Grange for a moth in 1818 along with Ary Scheffer, a Dutch painter, and historian Augustin Thierry. Notable other visitors included English philosopher Jeremy Bentham, American scholar George Ticknor, and Scottish writer, abolitionist, and feminist among others Frances Wright. Lafayette was also visited by many Americans in France.

Lafayette supported many French and other European conspiracies throughout the first decade of the Bourbon Restoration (which lasted from 1814 to 1830). The conspiracies all ended up being nothing though. He also involved himself in different plots made by the Carbonari. Lafayette traveled to Belfort, France to assume a role in the revolutionary government. He ended up not arriving in the city though, turning back when the royal government learned of him being involved in conspiracies so he could aoud overt involvement. When the Greek Revolution began in 1821, Lafayette als became a supporter of that. He even sent letters to American officials in hopes of persuading them to become allies with the Greek. Georges Washington was also involved in the efforts made by the Greek, causing Louis and his government to nearly arrest the both of them. The two were not arrested though because the government was wary of the possible political ramifications that could have happened. Up until 1823, Lafayette also remained in the Chamber of Duties. He was defeated when running for reelection because of recent plural voting rules having been put into place.

James Monroe, who had been president since 1817, and Congress invited the Frenchman to visit America after nearly forty years in 1824. Part of the reason they invited him was to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the United States. Monroe’s original intention was for Lafayette to travel from France on an American warship. Lafayette instead decided to book passage to America on a merchantman, feeling that Monroe’s idea was undemocratic. When a crowd gathered at Le Havre, Louis XVIII, who disapproved of the trip, made his officers disperse them.

On August 15, 1824, Lafayette arrived in New York with his son Georges Washington and secretary Auguste Levasseur at his side. Many veterans from the Revolutionary War greeted him when he arrived that day at Staten Island. The following day, the Lafayette Welcoming Parade of 1824 was held in the city to welcome the Marquis. His arrival in America was a celebration for all, the hero of the American Revolution finally returning forty years later. For four consecutive days and nights, celebration in New York City was held.

In what he hoped to be a peaceful trip to Boston, Lafayette departed to find citizens cheering and celebrating along the roads and in every town. In just about every town he passed, more celebrations were held for Lafayette. The three major cities, Boston, New York, and philadelphia all tried to have grander celebrations and outdo each other. Philadelphia renovated the Old State House, which is now Independence Hall and was where both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution were written and signed, so Lafayette and his staff and son could have a place to stay. The Hall had the possibility of being torn down, so perhaps renovations were a good thing. Many cities had commissioned portraits and monuments of the Frenchman to display. What was meant to be a four-month trip just to visit the original thirteen states turned into a sixteen-month trip where he visited all twenty-four states.

When he visited the first city named after himself, Fayetteville, North Carolina, he was welcomed with an even more enthusiastic welcome. Lafayette visited President Monroe in the new capital, Washington City, and was shocked to see hardly any guards around the White House and the president’s simple clothing. And for the first time, he visited George and Martha Washington’s graves at Mount Vernon while in Virginia. He then celebrated the anniversary of when Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown on October 19, 1824. Afterwards, while still in Virginia, Lafayette visited his old friend Thomas Jefferson with his close friend and successor James Madison at Jefferson’s Monticello estate. Lafayette also dined with former president John Adams at his home outside of Boston. Adams was eighty-nine at the time, having served as president from 1797-1801.

During the winter of 1824-25, Lafayette stayed in Washington City due to the roads being blocked off and impossible to pass through on. He was there when neither presidential candidate had secured enough electoral votes at the 1824 election. It was decided by the House of Representatives that John Quincy Adams would become president. Lafayette watched on the evening of February 9, 1825 as John Quincy Adams shook hands with General Andrew Jackson, who had been runner up in the election.

Finally, he left the capital in March and began towards the state in the south and west. The plan was that state militias would escort the marquis between cities. Specially constructed archways in each town made for Lafayette as local dignitaries and politicians greeted him. At every spot he visited special events such as dinners and battlefield and historic site visits were held with time for the public to meet with Lafayette, their legendary hero.

General Jackson greeted Lafayette at his Tennessee home called The Hermitage. Then, as he traveled up the Ohio River on a steamboat, it sank. With his son and secretary, Lafayette was able to get on a lifeboat and make it to the Kentucky shore, where he was met with another steamboat. The steamboat was headed in the opposite direction than Lafayette, but the captain insisted that they turn around and follow the frenchman’s route. Lafayette visited Louisville, Kentucky and then began heading northeast towards Niagara Falls and the Eerie Canal up to Albany. When he visited the Bunker Hill Monument after Daniel Webster had made a speech, he laid the cornerstone then took home some soil. When he died nine years later, that very soil was sprinkled over grave.

For the last part of the tour, Lafayette made his way up to Maine and Vermont, marking the twenty-fourth and last state for him to visit. Him and John Adams met once more before he returned to New York City and then Brooklyn. He laid down the public library’s cornerstone while he was at the latter. On September 6, 1825 President John Quincy Adams held a reception at the White House in celebration of Lafayette’s sixty-eighth birthday. The following day, he left for France with the Bunker Hill soil along with various other things he had been gifted. out of gratitude, James Monroe had convinced Congress to present Lafayette with $200,000 because of all he did for the country. He was also given a large piece of public land located in Florida. He sailed back on the USS Brandywine, which had been renamed from the Susquehanna in honor of The Battle of Brandywine, where Lafayette bravely fought and shed his blood.

As he was still in America, King Louis XVIII passed away on September 16, 1824 and was replaced by Charles X that same day. The new king had hopes to restore absolute rule to the monarchy. By the time Lafayette finally arrived home, a protest had already begun. Lafayette had been amongst one of the most notable protests of the king and monarchy. He was elected back onto the Chamber of Deputies in 1827 when he was seventy years old. Charles dissolved the Chamber upon Lafayette’s reelection, but he was only elected and won his seat back.

Lafayette often made fiery speeches in the Chamber as he was outspoken from the new restrictions on civil liberties and press censorship Charles had enacted. He denounced the new decrees Charles was continuously putting in place and advocated for a government more similar to that of America’s. Lafayette also continued holding dinner parties at La Grange where many Americans and Frenchmen alike dined with him. Everyone was eager to hear his political speeches on freedom, liberty, and rights. Charles, wanting to arrest him, realized the marquis was far too popular for it to be done safely. He did keep many spies though to investigate Lafayette.

The Ordinances of Saint-Cloud was signed by Charles on July 25, 1830. The middle class franchise was removed and the Chamber of Deputies dissolved. Riots began to erupt on July 27 as Parisians put up barricades around the city. The Chamber continued meeting though to defy the king. Lafayette raced into the city, abandoning La Grange, as soon as he heard what was happening. He was then acclaimed leader of the revolution, which became known as the July Revolution. The other deputies were indecisive, leaving Lafayette to the barricades as the royalist troops soon became routed. The deputies did make Lafayette head of the newly restored National Guard, charging him with keeping order in the city. But Lafayette refused the power, deeming it unconstitutional, when the Chamber was willing to proclaim him as ruler. While many people wanted a republic, Lafayette felt this could eventually lead to a Civil War. He continued to refuse listening and dealing with Charles. He decided to offer the throne to the duc d’Orleans, Louis-Philippe. Louis-Philippe had spent quite some time in America. Lafayette believed that, unlike Charles, he had more of a common touch. Louis-Philippe accepted the throne and Lafayette stayed the National Guard commander. The Chamber voted on December 24, 1830 to take away Lafayette’s command of the National Guard. In response, Lafayette expressed that he was willing to go into retirement once more, which was exactly what he did.

Louis-Philippe turned out to not be who Lafayette expected. He constantly backtracked on reform, denying any promises to make any as well. Lafayette was angry and broke with the new king. This breach became wider when the government had to suppress a strike in Lyon with force. Lafayette began promoting more liberal proposals with his Chamber seat. He was elected mayor of the village of La Grange in 1831 by his neighbors, who also elected him to the council of the département of Seine-et-Marne. Lafayette spoke at General Jean Maximilien Lamarque’s funeral the next year, also serving as a pallbearer. He continuously plead for peace and calm in France as more and more riots were occurring. At the Place de la Bastille, another barricade had been erected. King Louis-Philippe forcefully stopped the June Rebellion happening from June 5-June 6, 1832. This only outraged Lafayette even more with the king. Until he had to meet with the Chamber again in November, Lafayette made his way back to La Grange. Just as he had done with Charles X, Lafayette condemned Louis-Philippe for censorship.

For the last time, Lafayette made a public speech on January 3, 1834 in the Chamber of Deputies. While at a funeral the following month, he unexpectedly collapsed, having come in contact with pneumonia. Luckily, Lafayette recovered but spent the next few months bedridden after being caught in a thunderstorm that May.

Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette died on May 20, 1834 while in Paris at 6 rue d’Anjou-Saint-Honoré at seventy-six years old. He was buried beside his wife Adrienne in Paris at Picpus Cemetery with soil he had taken from Bunker Hill. Georges Washington hd even sprinkled the soil upon his father. Crows began to protest though when King Louis-Philippe ordered they hold a military funeral, preventing public attendance. Andrew Jackson, now United States President, ordered that they give Lafayette the same memorial honors as Washington had when he died in 1799. The Houses of Congress were draped for thirty days in black bunting as members donned mourning badges. Congress urged that the rest of America also follow mourning practices for their Revolutionary War hero. Later that year, John Quincy Adams gave a three hour eulogy of Lafayette.