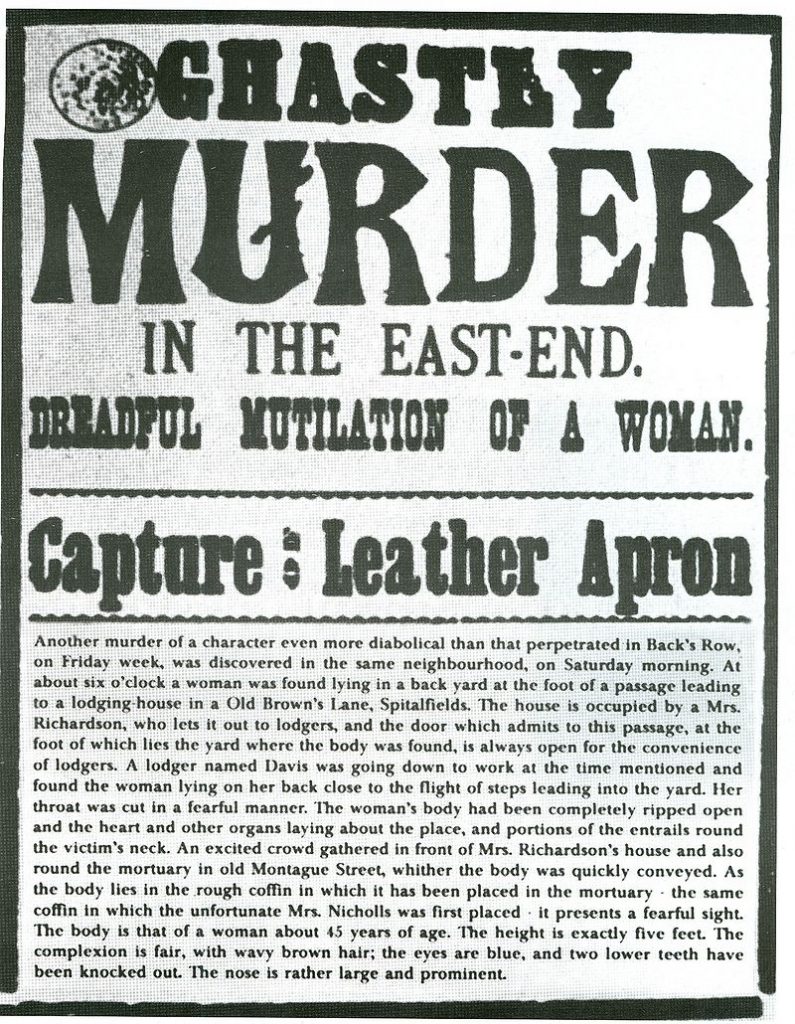

In the swirling, dark fog of factory smoke and London rain, a serial killer legend was born. Deep in the bowels of London’s east end, in the notorious district of Whitechapel, an unidentified serial killer slit the throats of young female prostitutes working in the area in 1888. The murders were never solved, and there are now over a hundred theories surrounding the killer’s true identity. He’s faded into a legend now, known across the world as “The Whitechapel Murderer”, “Leather Apron”, and, most famously: “Jack the Ripper”.

Background

It was the mid-19th century, the height of Victorian London as we know it today. Irish, Russian, and Jewish immigrants were streaming into England’s borders, overcrowding London’s poorer east end. Employers and landlords took advantage of these newcomers who had no laws protecting them. Crime skyrocketed, and out of this underbelly of Victorian society came one option for women locked in poverty’s thrall: prostitution. In October of 1888, when the Whitechapel Murders started, the London Police estimated that there were over 62 brothels in operation in Whitechapel alone, employing over 1,200 women.

Stories of violence, murder, and crime in Whitechapel fed the upper and middle classes’ antisemitism and disdain for the east end. By 1888, Whitechapel had gained notoriety as a den of immorality, and when a series of vicious, brutal murders of young prostitutes began to surface, the press swooped on the story, and the public ate it up.

The Five Canonical Murders of Whitechapel

Two other murders were originally included in the Ripper case file, but modern experts have excluded them. The first has been related to gang violence in the area. The victim was not killed immediately, and she said she was attacked by several men, instead of just one. The second victim had 36 stab wounds, which does not match the Ripper’s modus operandi, or M.O., of slashing and cutting patterns.

Each of the women in the canonical five had their throats cut, and four out of five had an organ removed. It’s clear from the examinations of the bodies that, as the Ripper killed, he escalated- a common pattern for serial killers. Two out of the five had their uterus surgically removed. One was not missing any organs, another was missing a kidney, and his fifth and final victim had been completely mutilated, her throat slashed down to the bone, the abdomen emptied of organs, and her heart was missing from the scene.

The murders happened at night, on or close to a weekend and near the end of a month.

The Search for Jack the Ripper

The investigation was headed by the Metropolis Police of London, with Detective Inspector Edmund Reid and Scotland Yard detectives Frederick Abberline, Henry Moore, and Walter Andrews leading.

While the police worked on finding the murderer, the public did too. A group of volunteers from Whitechapel, called the “Whitechapel Vigilance Committee” patrolled the streets, looking for suspects.

The Whitechapel Murders were quite a historic point for police investigations and forensic science, as they were, perhaps, one of the earliest and best documented examples of criminal profiling. Due to the nature of the murders, the detectives narrowed their suspects down to butchers, slaughterers, and even doctors and surgeons. Many thought that the Ripper belonged to a cattle boat. Whitechapel was near the London Docks, and the boats docked on Thursday or Friday and left the dock on Saturday or Sunday, which would directly coincide with the times of the murders. However, no boats were found that matched with the dates of the murders, and so that theory was ruled out.

The police surgeon working the case did not believe the murderer had any knowledge of anatomy, but thought instead that he was a homicidal maniac prone to episodes of violence. Some other people thought that, because the victims were prostitutes, the Ripper took sexual satisfaction in his kills, but that, too, was ruled out, as there was no evidence of sexual activity of any kind with the victims.

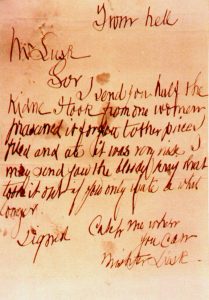

One other clue remained as to the Ripper’s identity. Over the course of the case investigation, many letters were sent to the police, claiming to be written by Jack the Ripper. Most of these were ruled out as hoaxes. Only three have been thought to be genuine, and only one is most likely to be written by the Ripper’s own hand. A letter signed From Hell was received by the leader of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee on October 16th, 1888. The handwriting was unique, and it came with a small box which held half a kidney preserved in ethanol. One of the recent victims, Eddowes, had had her left kidney removed by the Ripper. The letter claimed the Ripper had “fried and ate” half the kidney.

The kidney half was looked over by a doctor, who said that it did, indeed, appear to be human, and that it was from the left side.

The letter was published in newspapers, and the police asked if anybody recognized the handwriting, but no-one came forward.

Nobody could agree on one theory as to the Ripper’s identity. The police interviewed hundreds of suspects. By the time the case was abandoned, the lists of named suspects they were still watching was over a hundred men long.

An Open Case

In the end, in a strange twist of events, the Ripper ended up helping London’s east end. Before the murders, not much attention was paid to the overcrowded, horrific conditions of the London slums. The murders ignited the public’s opinion about the slums, and two decades after the murders, Whitechapel was almost completely cleared out and demolished.

Jack the Ripper has become something of a bogey man in popular fiction, a symbol of predatory aristocracy, and is almost always portrayed in novels and other works of fiction as a rich man in a top hat. Over a hundred standalone pieces have been written exclusively about Jack the Ripper, making it one of the most popular subjects of true-crime fiction in history. The real Jack the Ripper remains shrouded in myth and legend. The case remains open. In the end, there simply isn’t enough information to pinpoint one murderer.

In London, in a museum called “Madame Tussauds’ Chamber of Horrors”, many murderers have been depicted as waxwork figures. Not Jack the Ripper. True to form, he’s depicted there as he always existed: in obscurity, only shadow to haunt our minds and the dark places in our imaginations.