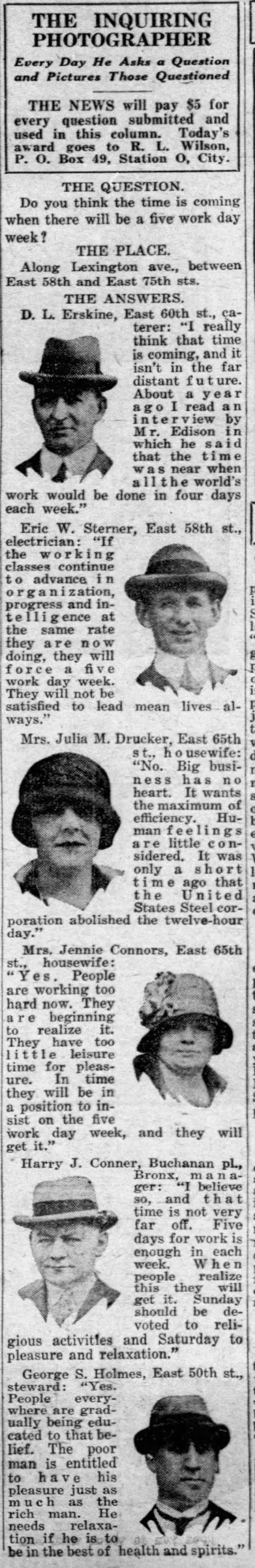

On May 6, 1925, a New York newspaper photographer walked the streets with a simple question: “Do you think the time is coming when there will be a five work day week?”

It sounded almost utopian. Most Americans still worked six days, often 50 to 60 hours a week. Sunday was a rest day. Saturday was a workday. The idea of a two‑day weekend felt like something from a labor rally, not normal life.

Yet within a generation, the five‑day workweek would be standard for millions of workers. The casual street question in 1925 captured a world on the edge of a major shift.

The five‑day workweek did not just appear by common sense or kindness. It grew out of strikes, religious pressure, corporate calculation, and new machines that changed what a day’s work even meant.

Here are five forces that turned that 1925 question into the modern weekend.

1. The brutal six‑day week that made the question urgent

Before anyone could dream about a five‑day week, there was the reality of the six‑day grind. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a “normal” workweek in American industry was six days, often 10 hours a day. That meant 60 hours or more on the job, with only Sunday off.

In 1890, U.S. manufacturing workers averaged about 60 hours a week. Even by 1920, after decades of agitation, the average was still around 50 hours. The 40‑hour week was not standard law, it was a demand on picket signs.

Take the steel industry. In 1910, many steelworkers endured the infamous “long turn,” a 24‑hour shift when the schedule rotated. Andrew Carnegie’s mills were known for 12‑hour days, seven days a week for some crews. A 1923 report by the U.S. Department of Labor described steel schedules as punishing and dangerous.

Or look at coal mining in West Virginia and Pennsylvania. Six days underground was normal. Injuries were common. Pay was low. When miners struck, shorter hours were almost always on the list, right next to wages and safety.

Even white‑collar workers were not living in a 9‑to‑5 dream. Clerks, shop workers, and office staff often worked half days on Saturday, sometimes longer in busy seasons. Department stores in cities like New York and Chicago stayed open late, and their employees stayed with them.

So when that “Inquiring Photographer” asked in 1925 about a five‑day week, it was not a cute thought experiment. It was a question born out of exhaustion. People knew what six days felt like. They knew what it did to family life, to health, to any hope of leisure.

The six‑day week mattered because it created the pressure cooker. Without that level of grind, there would have been no mass appetite for a shorter week, and the five‑day idea would have sounded like a luxury instead of a demand.

2. Religious demands: from the Jewish Sabbath to the “weekend”

One of the most overlooked drivers of the five‑day week was religion, especially the collision between the Christian Sunday and the Jewish Saturday Sabbath.

For most of the 19th century, American employers treated Sunday as the only legitimate day of rest. That lined up with Protestant norms. But as Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe surged in the late 1800s and early 1900s, millions of new workers brought a different sacred day: Saturday.

Jewish workers in factories and shops faced a brutal choice. Work on Saturday and break religious law, or refuse and risk their jobs. Many tried to keep Saturday and work Sunday instead, but employers often refused. That tension produced some of the earliest experiments with a two‑day break.

In 1908, a New England cotton mill in Manchester, New Hampshire, run by the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company, quietly tried something new. To accommodate its many Jewish workers, the mill closed on Saturday and Sunday, spreading the same weekly hours over five days. It was not charity. It was a way to keep a needed workforce.

In cities like New York, where Jewish communities were large, some garment shops and small factories began informally recognizing both Saturday and Sunday. They did not always cut hours. Sometimes they stretched the remaining days. But the idea that a “weekend” could mean two days, not one, started here.

Christian reformers also played a role. The “Lord’s Day” movement pushed to protect Sunday as a day of rest, arguing that long hours and seven‑day schedules were morally and physically destructive. Their campaigns did not invent the five‑day week, but they helped normalize the idea that time off was a social good, not laziness.

By the 1920s, the phrase “week‑end” was appearing in newspapers and ads, especially in Britain and the U.S. It did not always mean two full days yet, but the cultural idea was forming: workweek, then weekend, as a pair.

Religious pressure mattered because it forced employers to confront the problem of two different holy days. Solving that problem nudged them toward a two‑day break, which became the skeleton of the modern five‑day week.

3. Labor unions and the fight for “Eight hours for what we will”

If you want to know why the five‑day, 40‑hour week exists, you have to look at organized labor. Unions made shorter hours a central demand long before it was law.

In the late 1800s, the slogan of the eight‑hour movement summed it up: “Eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for what we will.” The first big push came on May 1, 1886, when workers across the U.S. struck for an eight‑hour day. The protests in Chicago led to the Haymarket affair, a bombing and a crackdown that scarred the labor movement but kept the issue alive.

For decades, unions fought factory by factory, industry by industry. The American Federation of Labor (AFL), led by Samuel Gompers, made shorter hours a core goal. So did the United Mine Workers, the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, and many others.

One concrete example: the 1919 steel strike. About 350,000 steelworkers walked off the job, demanding not just better pay but an eight‑hour day. The strike failed in the short term. The companies held firm, and the workers went back with few gains. But the public debate it sparked helped make long hours look outdated and abusive.

Another example: the 1912 “Bread and Roses” strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts. When textile mill owners cut pay after a new law reduced weekly hours, immigrant workers, many of them women, shut the mills down. Their slogan linked wages and time: they wanted bread, but also roses, meaning a life beyond the loom.

By the early 1920s, some unionized trades had won significant hour reductions. Building trades in big cities often had shorter weeks. Certain skilled workers had Saturdays off or half‑days. The idea of a 44‑ or 48‑hour week was gaining ground.

Unions did not invent the five‑day week as a neat package, but they hammered away at hours until the old 60‑hour norm cracked. They also pushed politicians. When the U.S. Congress debated labor laws in the 1910s and 1920s, union pressure was always in the background.

Labor’s fight mattered because it turned “less work” from a private wish into a public demand, backed by strikes, slogans, and votes. Without that pressure, employers and lawmakers had little reason to cut a sixth day off the calendar.

4. Henry Ford and the business case for a shorter week

Here is where many people get the story half right. Henry Ford did not invent the five‑day workweek, but he made it famous and proved it could pay.

Ford had already shocked industry in 1914 by doubling his factory workers’ pay to $5 a day while keeping an eight‑hour day. He claimed it reduced turnover and made workers productive enough to justify the cost. Critics called him reckless. Other companies quietly copied him.

In 1926, Ford Motor Company announced that it would move most of its operations to a five‑day, 40‑hour week, closing plants on Saturdays and Sundays. Some smaller firms and mills had tried similar schedules before, but Ford’s move was national news.

Ford’s reasoning was not sentimental. He believed shorter hours made workers more efficient and less likely to quit. He also had a larger vision: workers should have enough time and money to buy and enjoy the products they made. If they had weekends off, they might take Sunday drives in their Model Ts, go shopping, spend money. Leisure could feed industry.

Ford’s River Rouge complex in Dearborn, Michigan, became a symbol of this new model. A worker could earn a decent wage, work five days, and still be part of the mass production machine. It was hardly a paradise. The work was repetitive and tightly controlled. But compared to 12‑hour, six‑day mills, it looked almost modern.

Once Ford did it, other employers took notice. Some followed to compete for labor. Others feared that if they did not, unions would force them anyway. Newspapers ran stories about the “five‑day week” as a sign of progress.

Ford’s move mattered because it reframed shorter hours as smart business, not just a concession to labor. When one of the most famous industrialists in the world said a five‑day week could boost profits, it gave political cover and economic logic to an idea that had seemed radical.

5. The Great Depression, New Deal laws, and the 40‑hour week

The last big piece of the puzzle arrived not in the roaring 1920s but in the desperate 1930s. The Great Depression turned the hours debate into a national emergency question: if there is not enough work, should we spread it around by cutting the workweek?

In 1933, Senator Hugo Black of Alabama proposed a law to limit the workweek to 30 hours. The idea was simple. If each worker did fewer hours, more workers could be hired. The bill passed the Senate but stalled under pressure from business groups and some labor leaders who worried about wage cuts.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration took a different route. Through the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) of 1933, the government encouraged industries to write “codes” that set minimum wages and maximum hours. Many codes aimed at a 40‑ to 48‑hour week. The Supreme Court struck NIRA down in 1935, but the idea of federal hour limits was now on the table.

The decisive step came with the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938. The law, signed by Roosevelt, set a federal minimum wage and established that most covered workers would have a maximum 44‑hour week, which would drop to 40 hours over a few years. Any time beyond that required overtime pay at time‑and‑a‑half.

That overtime rule was key. Employers could no longer get extra hours for free. If they wanted a sixth day, they had to pay more. Many decided it was cheaper to hire more workers or reorganize schedules around a five‑day, 40‑hour pattern.

By the early 1940s, especially during World War II, the five‑day, 40‑hour week had become the standard expectation in many industries, even if wartime needs sometimes stretched it. Unions wrote it into contracts. Workers organized their lives around it. Saturday and Sunday became the default weekend.

The New Deal laws mattered because they locked the shorter week into national policy. What had been scattered experiments and private bargains became a legal floor. That gave the 1925 street‑corner question a definitive answer: yes, the five‑day workweek was coming, and now it was written into federal law.

The five‑day workweek did not arrive as a gift from enlightened bosses or inevitable progress. It came from a collision of forces: workers worn down by six‑day grinds, religious communities insisting on sacred time, unions organizing for shorter hours, industrialists like Henry Ford testing new schedules, and a federal government that finally drew a legal line at 40 hours.

When a New York photographer in 1925 asked passersby if they thought a five‑day week was coming, he was catching a moment when the old world and the new were overlapping. Some people had already tasted Saturdays off. Others could not imagine it.

Today, as people argue about four‑day weeks, remote work, and burnout, that 1925 question feels familiar. The five‑day week we treat as normal was once a radical idea, shaped by conflict and compromise. Knowing how it came to be is a reminder that work schedules are not natural laws. They are choices, fought over and changed, one hour at a time.

Frequently Asked Questions

When did the five-day workweek become common in the US?

The five-day workweek spread gradually in the 1920s and 1930s, but it became broadly standard after the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 set a 40-hour week (phased in from 44 hours) with mandatory overtime pay beyond that. By the early 1940s, many American workers in covered industries were on a five-day, 40-hour schedule.

Did Henry Ford invent the five-day, 40-hour workweek?

No. Some mills and factories experimented with shorter weeks before Ford. However, when Ford Motor Company adopted a five-day, 40-hour week in 1926, it drew national attention and showed other employers that such a schedule could be profitable. Ford popularized the model rather than inventing it.

Why did workers originally push for shorter hours?

Workers pushed for shorter hours because six-day, 60-hour weeks were exhausting and dangerous. Long shifts increased accidents, damaged health, and left little time for family or rest. Unions framed the demand as a right to a full life: eight hours for work, eight for rest, and eight for personal time.

How did religion influence the creation of the weekend?

Religion influenced the weekend through the clash between the Christian Sunday and the Jewish Saturday Sabbath. Jewish workers wanted Saturday off, while employers already closed on Sunday. To accommodate both days without losing workers, some factories and shops began closing on both Saturday and Sunday, helping create the two-day weekend pattern.