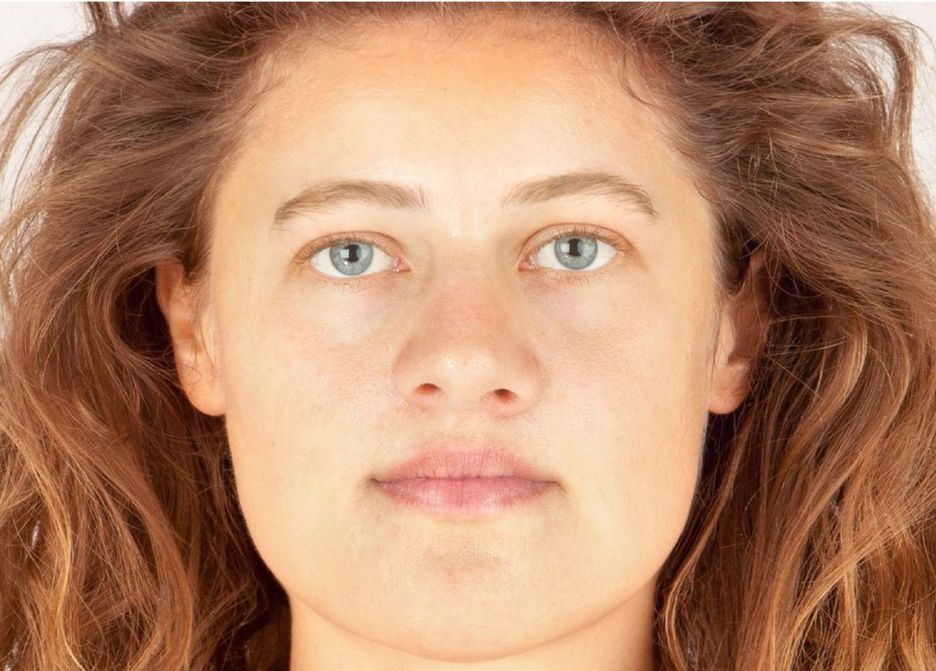

The face you’re looking at is 3,700 years old. Her name is Ava, and she was created using top-of-the-line facial reconstruction software and techniques by specialists working with the Caithness Horizons museum in Thurso, Scotland.

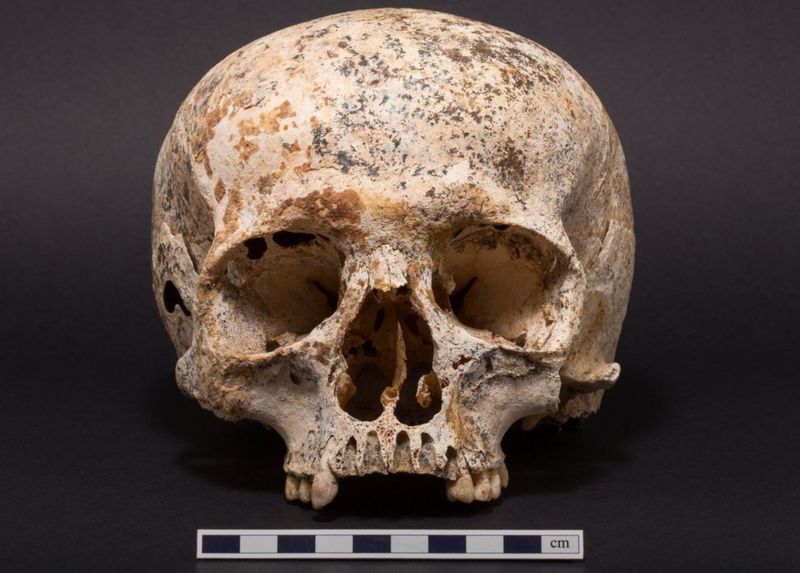

Archaeologists found Ava at Achavanich, in Caithness, Scotland, in 1987. She was buried in an unmarked pit dug into solid rock- an unusual burial. Most contemporary burials involved a cairn or a pit dug into soil. Maya Hoole, the archaeologist in charge of the site says “a lot of time and energy was invested in this burial…It just makes you wonder – why go to all that effort? What was so unique about the individual buried here to receive such special treatment?”

The body was found with a decorated beaker, one that seems to be unique. There’s nothing else in Europe like it. Researchers have determined that the makers of the beaker used at least three different tools to create it, tools coming from a bespoke tool kit.

That isn’t the only thing that’s special about Ava and her burial. Ava has been determined to come from the Beaker people: a bronze-age culture that was scattered all across prehistoric Europe. They’ve been known to have short, round skulls, but Ava is different. Ava’s skull is an abnormal, uneven shape. Archaeologists can’t decide whether or not this is because of a special genetic trait, or whether or not there was a head-binding practiced used to create Ava’s head shape.

Maya Hoole is passionate about this discovery. “I want people to remember that this is not just a cluster of bones,” she said, “…she was once a human being, with a name, an identity and a place in a long lost community.”

Archaeologists, scientists, and researchers have been trying to learn more about Ava and her story, and they’ve come just one step closer. They enlisted the help of Mr. Morrison, a graduate of Dundee’s Forensic Art MSc program. He’s a facial reconstruction specialist.

Using an anthropological formula, he calculated the shape of Ava’s missing lower jaw and figured out the thickness of her skin, using modern tissue depths for a reference.

He determined her size and shape of her lips using measurements taken of the width of the mouth, the position of her teeth, and the enamel on her teeth.

Then, drawing on a database of faces and an in-depth understanding of how bone structure affects tissue growth and shape, he rebuilt Ava’s face, layer by layer, and slowly brought her back to life.

So, today, we can look a prehistoric Scottish woman in the eye and see what our ancestors looked like.

It has to be taken with a grain of salt, however, as Mr. Morrison said:

“Normally, when working on a live, unidentified person’s case not so much detail would be given to skin tone, eye or hair color and hair style as none of these elements can be determined from the anatomy of the skull. So, creating a facial reconstruction based on archaeological remains is somewhat different in that a greater amount of artistic licence can be allowed.”

Ava’s facial reconstruction brings us one step closer to understanding our past. Maya Hoole will continue in future years to work on Ava’s remains and the site where she was found with her accompanying team of researchers. The pottery, the shape of Ava’s skull, and her unusual burial all tell a story of someone who was immensely significant to the people around her. Perhaps one day Ms. Hoole and her researchers will uncover the rest of Ava’s story.

“Being able to look at the faces of individuals from the past can give us a great opportunity to identify with our own ancient ancestors.” – Mr. Morrison, facial reconstruction specialist.