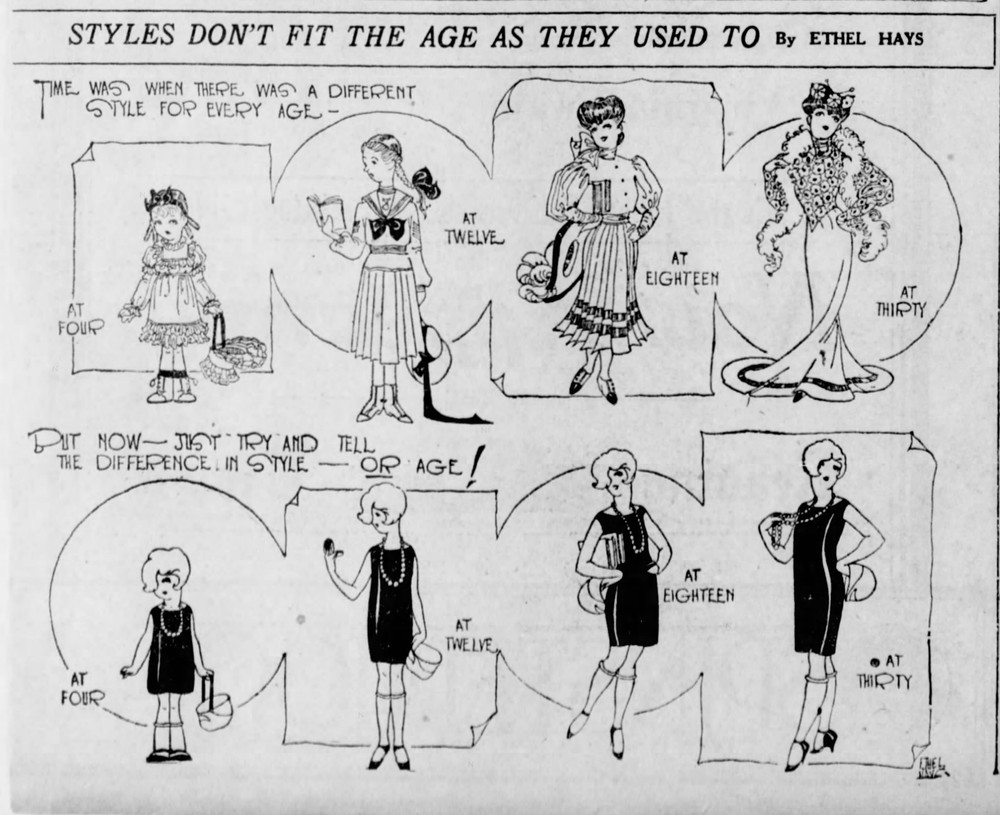

In December 1925, readers opened the newspaper and saw a young woman in a sleek, modern dress standing awkwardly inside an ornate, old-fashioned picture frame. The caption read: “Styles Don’t Fit The Age As They Used To.”

The artist was Ethel Hays, one of the sharpest cartoonists of the Jazz Age. In a single panel, she poked fun at the clash between old Victorian aesthetics and the new, streamlined 1920s world of bobbed hair, short skirts, and skyscrapers.

“Styles Don’t Fit The Age As They Used To” was not just a fashion joke. It was a commentary on a society that had changed faster than its art, manners, and expectations could keep up. By the end of this explainer, you will know what the cartoon was, what prompted it, who Ethel Hays was, and why this 1925 gag still feels familiar a century later.

What was “Styles Don’t Fit The Age As They Used To” in 1925?

“Styles Don’t Fit The Age As They Used To” was a single-panel newspaper cartoon by American cartoonist Ethel Hays, published on December 5, 1925. It appeared in the context of her regular work drawing modern young women and social satire for syndication in U.S. newspapers.

In essence, it was a visual joke about mismatch. A modern 1920s girl, with all the trappings of the flapper era, is squeezed into an older, ornate frame or setting that clearly belongs to a previous generation. The gag is that the “frame” of the past no longer fits the “content” of the present.

The cartoon’s title is a clean thesis statement: styles used to feel timeless, but in the 1920s, they aged fast. What once seemed proper and permanent now looked fussy and out of step with the times.

Put simply: Ethel Hays used a fashion cartoon to argue that the modern age had outgrown Victorian and Edwardian styles, both in clothing and in culture. The cartoon mattered because it gave ordinary readers a quick, funny way to recognize that they were living through a break with the past, not just a minor trend.

What set it off? The root causes behind the joke

Hays did not draw this cartoon in a vacuum. By 1925, the United States and much of Europe had been through a decade of upheaval: World War I, the 1918 flu pandemic, women’s suffrage, prohibition, and a massive economic boom. The world of 1905 felt ancient.

Fashion made that change visible. Before the war, women’s clothing meant long skirts, corsets, and elaborate hats. After the war, hemlines rose, waists dropped, and hair was bobbed. By the mid 1920s, a young woman in a straight, knee-length dress with shingled hair was a familiar sight in cities.

Art and design shifted too. Victorian interiors were crowded with heavy furniture and ornament. The 1920s brought cleaner lines and simpler forms. Art Deco, with its geometric patterns and metallic sheen, started to replace floral wallpaper and carved wood.

Technology added to the sense of rupture. Cars filled streets that had once been built for horses. Radios brought jazz and news into living rooms. Skyscrapers rose over older brick buildings. The speed of change made anything from the previous generation look instantly old-fashioned.

There was also a generational clash. Parents who had grown up in the 1880s or 1890s watched daughters cut their hair, shorten their skirts, drink in speakeasies, and dance the Charleston. Moralists complained that “modern girls” were shallow and immodest. Young women, in turn, saw their parents’ tastes as suffocating.

Cartoonists loved this tension. It was easy comedy: the old aunt in high-necked lace glaring at her niece’s bare knees, the father horrified by jazz records. Hays, who specialized in drawing modern young women, used that same tension but with a sharper point. Her 1925 cartoon suggested that the problem was not just rebellious youth, but the fact that the old cultural “frame” no longer fit the new world.

So what? Because the cartoon sprang from these broader social changes, it captured more than a passing fad. It distilled a decade of war, technology, and generational conflict into a single, instantly understandable image.

The turning point: Why late 1925 mattered for style

By December 1925, the “Roaring Twenties” were not just starting. They were in full swing.

In fashion, 1925 was near the peak of the classic flapper look. Hemlines hovered around the knee. Designers like Coco Chanel had popularized the loose, straight silhouette that freed women from corsets. Mass-market pattern companies and department stores spread these styles far beyond Paris and New York elites.

In Paris that same year, the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes (held from April to October 1925) gave a name and a platform to what we now call Art Deco. Visitors saw bold, geometric designs in furniture, jewelry, posters, and architecture. The message was clear: the future would not look like Grandma’s parlor.

In the United States, 1925 also marked the height of the “New Woman” debate. The 19th Amendment had granted women the right to vote in 1920. By mid-decade, women were not only voting but working in offices, going to college in higher numbers, and appearing in advertising as independent consumers.

Newspapers and magazines churned out think pieces about whether the flapper was a symptom of moral decay or a symbol of progress. Cartoons were part of that conversation. They were quick, cheap, and widely read.

Hays’s cartoon landed at the moment when the new style had become mainstream enough to be recognizable, but still controversial enough to feel like a challenge to the old order. It was less about a quirky new fashion and more about a tipping point where the old style could no longer claim to be the default.

So what? The timing meant that “Styles Don’t Fit The Age As They Used To” did not just describe a trend, it marked the moment when the 1920s stopped being an experiment and became the new normal, leaving the Victorian world definitively behind.

Who drove it? Ethel Hays and the women behind the flapper image

Ethel Hays was born in 1892 and trained as an artist. She studied at the Los Angeles School of Art and Design and later at the Art Students League in New York. She initially aimed for a career in serious illustration, but the demand for cartoonists and the popularity of comic art pulled her toward newspaper work.

By the early 1920s, Hays had become known for drawing stylish young women. Her figures had big eyes, expressive faces, and the unmistakable bobbed hair of the era. She drew for syndicates that distributed her work across the country, so her images reached millions of readers.

Hays was part of a small but growing group of women cartoonists. Names like Nell Brinkley, Gladys Parker, and later, cartoonists such as Marjorie Henderson Buell (creator of Little Lulu) showed that women could shape the popular image of femininity, not just appear in it.

Nell Brinkley, a bit older than Hays, had already made her mark in the 1910s with the “Brinkley Girl,” a romantic, flowing-haired heroine. Hays’s women were different. They were sharper, more modern, less sentimental. You can almost feel the shift from Edwardian romance to Jazz Age irony in the way she drew a raised eyebrow.

In “Styles Don’t Fit The Age As They Used To,” Hays used her skill with expressions and body language to sell the joke. The modern girl is not just misplaced, she looks uncomfortable, maybe a bit annoyed, at being stuck in an outdated frame. That expression carries the social commentary: the new generation is not content to be squeezed into old roles.

It matters that a woman drew this. Male cartoonists often mocked flappers as silly, vain, or morally loose. Hays could still make fun of fashion and youth culture, but she tended to draw her modern girls with wit and agency. They were in on the joke.

So what? Because Ethel Hays and other women cartoonists shaped how millions saw the “modern girl,” their work was not just decoration. It helped define what felt modern and what felt outdated, and it gave women a visual language to see themselves as part of a new age.

What did it change? The cartoon’s place in a bigger cultural shift

On its own, one cartoon does not change the world. But cartoons like “Styles Don’t Fit The Age As They Used To” did help normalize the idea that the past was not sacred and that styles could and should change with the times.

First, they made modern fashion seem ordinary. When readers saw flapper figures in daily comics, advertisements, and magazine art, the shock value faded. The bobbed hair and short skirt became a standard visual shorthand for “young woman,” not a scandal.

Second, they trained readers to see style as a marker of generational identity. Clothes and design were not just personal taste. They were symbols of being modern or old-fashioned, progressive or stuck in the past. That idea has never really gone away.

Third, they chipped away at the authority of Victorian aesthetics. The ornate frame in Hays’s cartoon is not treated with reverence. It is a prop in a joke. Once you can laugh at the old style, you can replace it.

In the longer run, the 1920s visual language that Hays helped popularize fed into later comic art and illustration. The big-eyed, stylized girls of mid-century greeting cards and advertisements owe something to her generation of cartoonists. So do later comic strips that center on modern young women navigating social expectations.

So what? The cartoon helped shift style from something inherited to something chosen, and it helped cement the idea that each age has its own look, with the right to discard what came before.

Why it still matters: Seeing our own style wars in 1925

A century later, “Styles Don’t Fit The Age As They Used To” feels oddly current. We still argue about whether new styles “fit” the times or betray some older standard.

Think about debates over skinny jeans versus baggy pants, natural hair versus straightened hair, or minimalist tech design versus retro aesthetics. Each argument is really about more than fabric or fonts. It is about who gets to define what feels modern and respectable.

Hays’s cartoon also speaks to how fast change can make the recent past look absurd. Someone born in 2005 might look at a 2012 smartphone or a 2010s outfit and see it the way a 1925 flapper saw her mother’s corset. The feeling that “styles don’t fit the age” is a recurring symptom of rapid cultural and technological change.

There is another reason the cartoon matters. It reminds us that women were not just passive subjects of the Jazz Age revolution. They drew it, wrote it, and joked about it. Ethel Hays and her peers were not simply recording the new style. They were helping to define it and to argue, visually, that the old frame no longer worked.

For anyone scrolling through a 100-years-ago subreddit and wondering why a 1925 cartoon about fashion is worth a second look, that is the answer. It is not only about hemlines. It is about a society realizing, with a mix of excitement and discomfort, that it had outgrown its inherited shape.

So what? Because the questions Hays raised in ink in 1925 are the same ones we ask in pixels today: When does a style stop fitting the age, and who gets to say when it is time for a new frame?

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Ethel Hays’ 1925 cartoon “Styles Don’t Fit The Age As They Used To” about?

Ethel Hays’ 1925 cartoon “Styles Don’t Fit The Age As They Used To” shows a modern 1920s woman awkwardly placed in an ornate, old-fashioned setting or frame. The joke is that the new flapper style no longer fits the Victorian and Edwardian aesthetic. It is a visual commentary on how quickly fashion and culture had changed in the 1920s.

Who was Ethel Hays and why was she important?

Ethel Hays (born 1892) was an American cartoonist and illustrator known for drawing stylish young women in the 1920s and 1930s. Working for newspaper syndicates, she helped popularize the image of the modern flapper and was part of a small group of women cartoonists who shaped how femininity and modernity were portrayed in mass media.

Why did styles change so fast in the 1920s?

Styles changed quickly in the 1920s because of the impact of World War I, technological advances, economic growth, and social shifts like women’s suffrage. Shorter skirts, bobbed hair, and simpler designs reflected a desire for freedom, practicality, and a break with Victorian constraints. New mass media and consumer culture spread these styles rapidly.

What does the cartoon “Styles Don’t Fit The Age As They Used To” tell us about the 1920s?

The cartoon shows that people in the 1920s were aware they were living in a new era that did not match the values and aesthetics of their parents. It reveals a generational divide, the normalization of flapper fashion, and a growing belief that each age has its own style instead of inheriting one fixed standard from the past.