She is standing very straight, hands folded, eyes fixed on something beyond the camera. Her dress is heavy and embroidered, a headscarf frames her face, and everything about her says “ceremony,” not “travel.” Behind her, out of frame, lies the chaos of Ellis Island: shouting inspectors, crying children, the smell of disinfectant and sea salt.

The woman is one of dozens of immigrants photographed between 1906 and 1914 by Augustus Frederick Sherman, a clerk at Ellis Island who quietly built one of the most famous visual records of the “new immigration” to the United States. His portraits, often shared online today, raise a lot of questions. Who were these people? Why are they in such elaborate clothes? Were they typical, or exceptions? And what was really happening to them before and after the shutter clicked?

Ellis Island was the main federal immigration station in the United States from 1892 to 1954. Between 1900 and 1914 it processed millions of arrivals from southern and eastern Europe and beyond. Sherman’s photos capture some of those people at the exact moment when their old lives had ended and their new ones had not yet begun.

Who was Augustus Sherman and why was he taking photos?

Augustus Frederick Sherman was not a famous photographer. He was a bureaucrat.

Born in Pennsylvania in 1865, Sherman joined the federal immigration service and by the early 1900s worked as a chief clerk at Ellis Island. He was not an inspector with the power to admit or exclude. He was one of the white-collar workers who kept the place running: paperwork, records, internal coordination. Somewhere along the way, he picked up a camera.

By 1906, Sherman was photographing immigrants who passed through Ellis Island. He did this on his own initiative, not as part of an official government program. He had access to people who were being detained for extra questioning or medical review, or who simply had time to wait. Those were the people he could ask to sit or stand for a portrait.

His images began circulating inside the immigration bureaucracy. The Commissioner-General of Immigration used some of them in annual reports. A few appeared in magazines and newspapers as visual proof of the “types” of people arriving in America. In 1907, National Geographic published several of his photos in an article about immigration.

Sherman never became famous in his own lifetime. His name was largely forgotten until the late 20th century, when the Ellis Island archives were combed for material and his glass plate negatives resurfaced. By then, his work had become one of the most widely reproduced visual records of Ellis Island.

Because Sherman was a clerk with daily access to detained immigrants, his camera captured people in a limbo that most photographers never saw. That access shaped the images that now define how many people imagine Ellis Island.

Why do Ellis Island immigrants look so dressed up in these photos?

One of the first reactions modern viewers have to Sherman’s images is confusion: why do these supposedly poor, desperate immigrants look like they are in costume for a festival?

There are a few reasons.

First, for many immigrants the journey to America was the most significant event of their lives. They wore their best clothes for travel, the way people once dressed up to fly on airplanes. For rural villagers from eastern or southern Europe, “best clothes” often meant traditional regional dress: embroidered blouses, layered skirts, elaborate headscarves, vests, and jewelry.

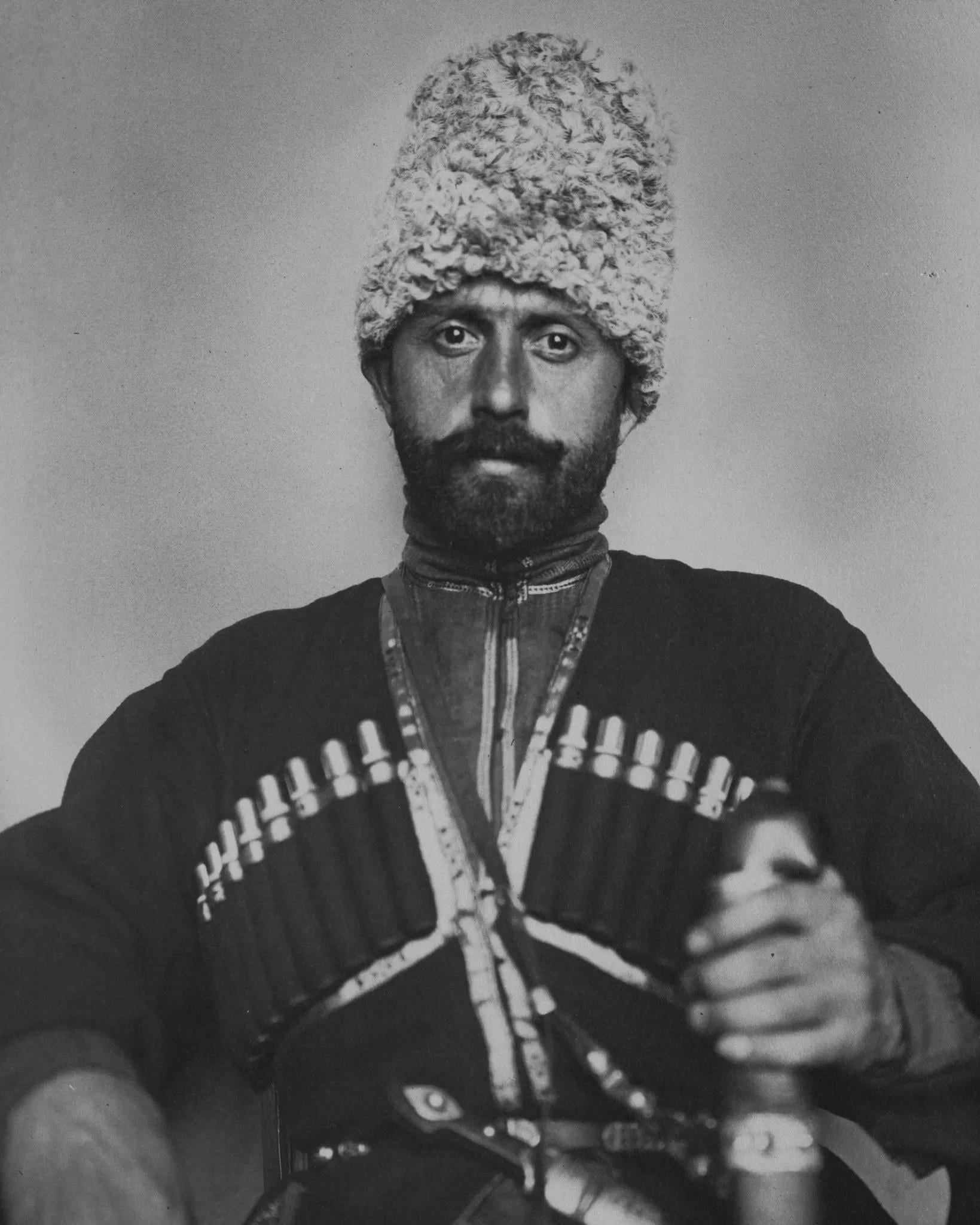

Second, Sherman was not photographing random people in the inspection line. He often chose those whose outfits were visually striking or who represented a “type” that interested him or his superiors. Albanians in national costume. Ruthenian women in embroidered dress. A Greek Orthodox priest in full robes. A Romani family. A group of Dutch children in wooden shoes. These were not average New Yorkers. They were, in the eyes of the era, ethnographic specimens.

Third, many of his subjects were detained for days or weeks for legal or medical reasons. They had time. They were not rushing to catch a train. Sherman could ask them to pose, adjust their stance, and wait for the long exposures that early cameras required. That is why so many of the portraits feel formal and composed rather than hurried.

Finally, the photos freeze a moment that was about to vanish. Many immigrants did not keep wearing folk dress once they settled in American cities. Clothes wore out. Children refused to wear what marked them as “greenhorns.” Within a few years, many of these outfits would be replaced by American ready-made clothing.

The result is that Sherman’s photos exaggerate how “traditional” Ellis Island looked. They show the most visually striking arrivals, in their best clothes, at the one moment when they still looked like people from “the old country.” That visual bias matters because it shapes how later generations imagine who came through Ellis Island.

Who actually passed through Ellis Island from 1906 to 1914?

Between 1900 and the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Ellis Island processed millions of immigrants. In 1907 alone, more than 1 million people arrived through the port of New York. The peak years of Sherman’s photography, 1906 to 1914, overlapped with the peak years of mass migration.

The composition of that flow had changed. Earlier in the 19th century, most immigrants came from northern and western Europe: Britain, Ireland, Germany, Scandinavia. By the early 1900s, the majority were coming from southern and eastern Europe: Italy, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Russian Empire, the Balkans, the Ottoman Empire. There were also smaller numbers from the Middle East and Asia, though Asian immigration was sharply restricted by law.

Sherman’s subjects reflect this shift. His plates show Italians from Calabria and Sicily. Slovaks and Ruthenians from the Carpathian region. Jews from the Russian Empire. Albanians, Greeks, and Armenians. A few images show people from Syria or the broader Levant, then part of the Ottoman Empire.

Most of these immigrants were poor, but not destitute. They had enough money for a steamship ticket and for the small sums required by American authorities. They were usually young adults, often traveling alone or in small family groups. Many were peasants or unskilled laborers. Others were artisans, small traders, or religious figures.

Not everyone who arrived stayed. Some were rejected for medical reasons, like trachoma, or for being judged “likely to become a public charge.” Some were sent back because of criminal records or because they failed literacy tests introduced later. But the majority were admitted after a brief inspection.

Ellis Island was a federal processing station, not the entry point for every immigrant. Canadians, Mexicans, and others who crossed land borders did not pass through it. Neither did many first- and second-class passengers, who were inspected on board ship or at the piers. Sherman’s photos capture a subset of the total immigrant story, one centered on steerage passengers arriving in New York.

By focusing on people from southern and eastern Europe in the peak years of mass migration, the photos freeze the moment when the ethnic makeup of the United States was being reshaped in ways that would echo through the 20th century.

What actually happened to immigrants at Ellis Island?

The romantic image of Ellis Island is of a gateway. The reality felt more like a factory.

Ships anchored in New York Harbor. First- and second-class passengers were inspected quickly and usually cleared on board or at the dock. Steerage passengers, the ones most people picture when they think of Ellis Island, were ferried to the island itself.

They entered the main building and climbed a long staircase. Doctors watched them as they walked, looking for limps, labored breathing, or signs of illness. At the top, they filed through the Great Hall, a cavernous room where inspectors checked papers, asked questions about destination and work plans, and assessed whether someone was likely to become a “public charge.”

Medical inspectors performed quick checks, sometimes marking coats with chalk letters indicating suspected conditions. Those who passed were usually through in a few hours. Those who did not were sent to further examination rooms, hospital wards, or detention areas.

The people in Sherman’s portraits were often in that second group. They might be waiting for a relative to be located, for a legal hearing, or for a medical decision. They might be held for days. That waiting created the opportunity for portraits.

Conditions varied. Some remembered Ellis Island as frightening and humiliating. Others remembered it as efficient and less harsh than the journey itself. Children sometimes recalled it as a blur of noise and new smells. The record is full of both gratitude and resentment.

Only a small percentage of arrivals were rejected, but the threat of exclusion hung over everyone. A chalk mark on a coat could mean the difference between a new life and a forced return. That tension is part of what you see in the faces in Sherman’s photos: a mix of exhaustion, hope, and apprehension.

By showing immigrants in the limbo of inspection and detention, Sherman’s portraits capture the gatekeeping power of Ellis Island at the exact moment the United States was deciding who counted as fit to join the national story.

Were Sherman’s photos neutral documentation or propaganda?

Modern viewers often assume that historical photos are neutral evidence. Sherman’s work is a reminder that every image is framed by someone’s choices.

Sherman chose who to photograph. He favored people whose clothes or appearance marked them as culturally distinctive. That choice fit the era’s fascination with “types” and “races.” At the time, many Americans believed that southern and eastern Europeans were racially different from earlier immigrants. Scientists measured skulls. Politicians warned of “undesirable” stock.

When Sherman’s images appeared in official reports or magazines, they were often used to support arguments about immigration policy. A photo of a Romani family might be presented as evidence of exotic “others.” A group of neatly dressed Dutch children could reassure readers that some immigrants were “like us.” The same image could be read as a celebration of diversity or as a warning about foreignness, depending on the caption and the viewer.

We do not have Sherman’s private thoughts about his subjects. His surviving notes are sparse, usually just labels like “Albanian woman” or “Romanian shepherd.” Some historians see empathy in the care with which he posed people and in the dignity of their presentation. Others see a collector’s eye, arranging human beings as interesting specimens.

Either way, the photos are not a random slice of Ellis Island life. They are curated. They emphasize traditional dress, solemn poses, and ethnic difference. They largely omit the chaos of the inspection lines, the overcrowded waiting rooms, and the more ordinary-looking migrants already dressed in plain work clothes.

Today, Sherman’s photos are often shared online as symbols of American openness or as proof that “our ancestors were immigrants too.” In their own time, they were part of a heated argument about whether the United States should keep its doors open at all. That double life gives them a complicated legacy.

Because Sherman’s images were used both to humanize and to categorize immigrants, they shaped public perceptions in ways that fed into the political fight over who should be allowed into the country.

How did this era of immigration end, and what happened to Sherman’s subjects?

The world that produced Sherman’s Ellis Island portraits did not last long.

In 1914, World War I broke out. Transatlantic travel collapsed. Immigration from Europe dropped sharply, not because of American law but because of war, blockades, and danger at sea. Ellis Island shifted from mass processing to other roles, including housing enemy aliens and serving as a detention center.

In the 1920s, the United States passed a series of restrictive immigration laws. The Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and the Immigration Act of 1924 set strict national quotas that heavily favored immigrants from northern and western Europe and sharply limited those from southern and eastern Europe. The era of mass “new immigration” through Ellis Island was over.

As for the people in Sherman’s photos, their individual stories are mostly lost. A few have been tentatively identified by descendants comparing family photos. Most remain anonymous. We can guess at their paths. Many likely went to industrial cities in the Northeast and Midwest: New York, Chicago, Pittsburgh, Cleveland. Italians often found work in construction and factories. Eastern European Jews crowded into tenements and garment shops. Slavs and southern Europeans went into mines, mills, and railroads.

Some would have American-born children who never saw the old country. Others would save enough to bring over relatives. A few might have returned to Europe, disillusioned or homesick. Some never got past Ellis Island at all.

By the mid-20th century, the children and grandchildren of these immigrants were part of the American middle class. Their old-country clothes were gone, replaced by suits, factory uniforms, and school dresses. Many changed names or softened accents. The folk costumes that looked so ordinary in Sherman’s time began to look exotic even to their descendants.

Ellis Island itself closed as an immigration station in 1954. The buildings decayed. In the 1980s and 1990s, the main building was restored as a museum. Sherman’s glass plate negatives, stored in the National Archives and at the Ellis Island museum, were cleaned, cataloged, and published.

By the time Sherman’s portraits reemerged in books and on the internet, the people in them were long dead. What remained were faces and clothes, floating free of their full stories. That gap between image and biography is part of why the photos fascinate modern viewers.

The end of mass Ellis Island immigration and the later rediscovery of Sherman’s work turned his once-obscure hobby into a central visual record of a closed chapter in American immigration history.

Why do Sherman’s Ellis Island photos still matter today?

In an era of digital images and border debates, Sherman’s portraits have taken on new life.

They are widely shared as proof that “our ancestors were once the strangers.” The Albanian woman in embroidered dress, the Jewish man with a long beard, the Italian family in heavy shawls are used to argue that yesterday’s “undesirables” became today’s mainstream Americans. The photos become a quiet rebuke to those who insist that current immigrants are uniquely foreign or unassimilable.

At the same time, the images can be misread. Because they focus on traditional dress and solemn poses, they can flatten the diversity of the immigrant experience into a series of quaint “ethnic” types. They can feed nostalgia that forgets the discrimination, labor exploitation, and political fights that greeted these arrivals.

They also raise questions about consent and representation. These people did not pose for a global audience. They were in a vulnerable position, subject to the authority of the institution where Sherman worked. Their images are now used in ways they could never have imagined, from museum walls to social media posts.

Yet the power of the portraits is hard to deny. The direct gaze of many subjects cuts across a century. You can see tired eyes, stiff backs, children trying to hold still. The clothes may be foreign, but the expressions feel familiar.

For historians, the photos are a rare visual source on the clothing, hairstyles, and self-presentation of early 20th-century migrants. For families, they offer a way to imagine ancestors whose own photos did not survive. For anyone thinking about immigration policy, they are a reminder that debates over who belongs are not new.

By freezing the moment when millions of newcomers were about to become part of the United States, Sherman’s Ellis Island portraits keep forcing the same question back onto the present: who do we see when we look at the people at our borders, and what stories will our images tell about them a hundred years from now?

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was Augustus Sherman and what did he do at Ellis Island?

Augustus Frederick Sherman was a chief clerk at Ellis Island in the early 1900s. Between about 1906 and 1914 he photographed detained immigrants, creating a famous series of portraits that documented people arriving from southern and eastern Europe and other regions during the peak years of Ellis Island immigration.

Why are immigrants in Ellis Island photos wearing traditional or fancy clothes?

Many immigrants wore their best clothes for the journey to America, which for rural Europeans often meant traditional regional dress. Augustus Sherman also chose visually striking subjects, such as people in folk costumes or religious garments, and photographed them while they were detained and had time to pose. That combination makes the photos look more formal and “traditional” than the average immigrant’s daily appearance.

Were the people in Augustus Sherman’s Ellis Island photos typical immigrants?

They were typical in the sense that many came from the same regions and social backgrounds as millions of other immigrants, especially southern and eastern Europe. But they were not a random sample. Sherman often photographed people in distinctive dress or those detained for extra inspection, so his portraits overrepresent the most visually striking and unusual cases compared to the broader immigrant population.

What happened to most immigrants who passed through Ellis Island?

Most immigrants who passed through Ellis Island were processed in a matter of hours and admitted to the United States. A smaller number were detained for medical or legal reasons, and a minority were rejected and sent back. Those admitted usually traveled on to cities and industrial regions, where they worked in factories, mines, construction, and small trades, and their children and grandchildren became part of American society.