They look similar because, at first glance, it is just another story of Rome crushing a barbarian revolt. A tribal queen rebels, a few cities burn, the legions return, order is restored. But the story of Queen Boudica and the Roman Empire is not a generic frontier skirmish. It is a collision between two very different ideas of power, justice, and revenge, written in blood and ash under what is now central London.

In 60 or 61 CE, after Roman officials flogged Boudica and her daughters were raped by soldiers, the Iceni queen led a revolt that destroyed three Roman centers: Camulodunum (Colchester), Londinium (London), and Verulamium (St Albans). Londinium burned so hot that archaeologists today still find a thick black-red burn layer, the “Boudican Destruction Horizon,” running under modern streets and office towers.

By the end of this story, you can see Boudica not as a cartoon of barbarian fury but as a ruler making hard, brutal choices under occupation, and Rome not as a faceless empire but as a machine that could be both legalistic and savage. They look similar as two sides locked in a simple war, but their origins, methods, outcomes, and legacies pull in very different directions.

How did Boudica’s revolt begin, and why was Rome in Britain at all?

Start with two facts that sit awkwardly next to each other. Around 43 CE, Emperor Claudius invaded Britain, claiming it for Rome. Around 60 CE, a Roman official had a queen stripped and whipped while her daughters were assaulted. Those two facts are connected.

Rome came to Britain for the usual reasons: prestige for the emperor, new tax revenue, and access to resources like metals. The Iceni, Boudica’s people in what is now Norfolk, were not conquered outright at first. They were a client kingdom, ruled by King Prasutagus, who kept his throne by cooperating with Rome.

Prasutagus tried to play Roman rules. When he died, he reportedly left his kingdom jointly to his two daughters and the emperor Nero, hoping to protect his family and tribe. That was a very Roman-style legal move. It did not work.

Roman officials treated his will as an opening, not a contract. The procurator Catus Decianus moved to annex Iceni lands directly. Property was seized. Nobles were treated as slaves. Boudica, now widowed queen, was flogged. Her daughters were raped. Tacitus, our main source, presents this as a deliberate act of intimidation and punishment.

So on one side you have Rome, an empire that justified conquest with law and order but could turn vicious when money and control were at stake. On the other side you have Boudica, a queen who had tried to live within that system and saw it humiliate her and her children.

They look similar as political actors trying to hold power. The difference is that Rome had an empire behind it. Boudica had rage, wounded honor, and tribes who felt they had nothing left to lose. That imbalance set the trajectory of everything that followed.

So what? The origins matter because they show Boudica’s revolt was not random savagery but a reaction to specific Roman abuses and broken promises, which shaped both her support and her fury.

What were Boudica’s methods compared to Roman military tactics?

When Boudica moved, she moved fast. Around 60/61 CE, the Roman governor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus was off in north Wales attacking the island of Mona (Anglesey), a Druid and tribal stronghold. Much of the Roman military muscle in Britain was with him. That left the southeast exposed.

Boudica and her allies, including parts of the Trinovantes and perhaps other tribes, chose shock and terror as their method. They attacked Camulodunum first, the Roman colony at Colchester. It was a symbol of occupation, full of retired legionaries and a temple to the deified Claudius. The defenders had few troops and a half-built wall. The city was overrun and destroyed. Archaeology shows a burn layer and smashed statues, including parts of a statue of Nero.

Next came Londinium. This was not yet the capital of Roman Britain, but it was already a busy commercial hub on the Thames. Suetonius raced back with a small force, looked at the odds, and made a cold decision. He evacuated the town and abandoned it to its fate. Boudica’s forces entered and burned it to the ground. The heat was so intense that clay tiles warped, and a distinct red-black ash layer formed. That is the Boudican Destruction Horizon archaeologists still trace under the City and parts of Southwark.

Verulamium (near modern St Albans) fell next. Tacitus and Cassius Dio both describe mass killings, torture, and ritualized cruelty by the rebels. They are Roman writers with their own agenda, but the archaeological record supports large-scale destruction. Boudica’s method was clear: target Romanized centers, wipe them out, and send a message that Rome could not protect its own.

Rome’s method was the opposite: discipline, formation, and patience. Suetonius refused to be drawn into fighting in streets or forests. He waited until he could choose the ground, likely along a Roman road with a narrow approach and woods at his back. When the final battle came, Boudica’s larger force, packed with warriors and camp followers, charged a disciplined Roman line. The legions used javelins, tight formations, and a counterattack that turned the Britons’ numbers into a liability, especially when their own wagons blocked retreat.

They look similar if you just count bodies. Both sides killed on a large scale. The difference is in method and purpose. Boudica used fire and massacre to erase symbols of occupation and to rally support. Rome used controlled violence to restore fear and order.

So what? The contrast in methods explains why Boudica could destroy cities but could not win the war, and why Rome could lose tens of thousands of civilians yet still reassert control with a single well-chosen battle.

What actually happened to those three cities, and how do we know?

The Reddit post that sparked this comparison focuses on a vivid detail: Londinium burned so fiercely that a blackened layer still lies under modern London. That is not internet exaggeration. It is one of the clearest archaeological scars of a specific historical event in Britain.

At Camulodunum, excavations have found a thick destruction layer from the mid-first century CE. Burned buildings, collapsed walls, and smashed statuary match the written accounts of a sudden, violent sack. The temple of Claudius shows signs of a siege and fiery end.

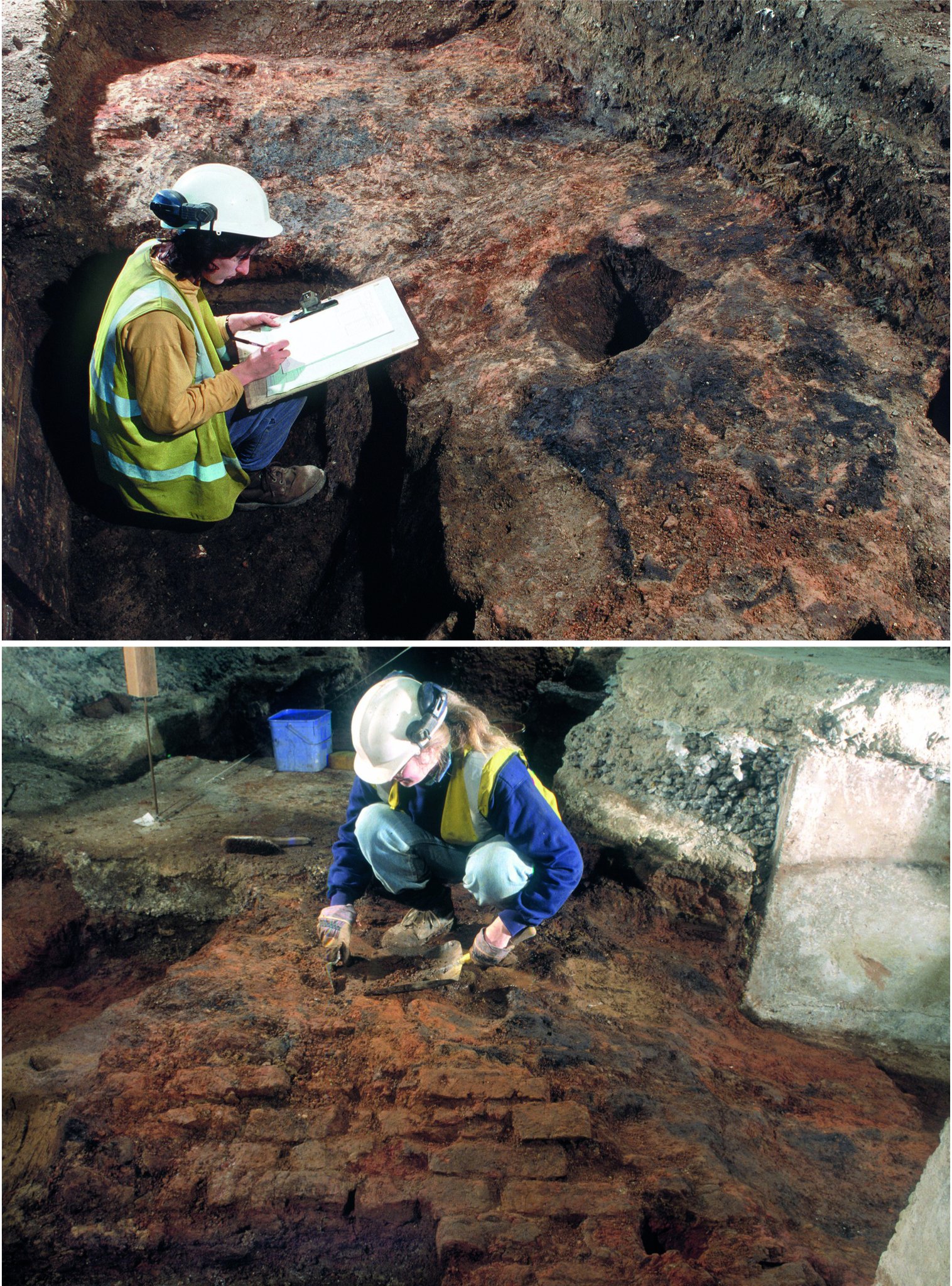

In Londinium, the Boudican Destruction Horizon is a distinct band of red and black debris, often 10 to 30 centimeters thick, dated to around 60–61 CE. It contains charred timbers, burnt grain, melted glass, and household goods. In some places, there are human remains. The layer runs under parts of the modern financial district and beyond. Above it, later Roman rebuilding begins.

Verulamium shows a similar burn layer and a gap in occupation, followed by rebuilding with more Roman-style stone structures. Together, these three destruction layers line up in date and character. They match the sequence described by Tacitus: Camulodunum first, then Londinium, then Verulamium.

So when people ask if Boudica “destroyed three entire cities,” the answer is: she and her followers destroyed the Roman towns that were there at the time. These were not modern cities of millions, but they were dense settlements, administrative and economic hubs, and they were thoroughly burned.

They look similar in the ground: black ash, broken walls, sudden endings. The difference is what came after. Roman towns rose again on the same sites. The Iceni and their allies did not.

So what? The archaeological layers matter because they turn a literary story of revenge into something you can literally stand above in a Tube station, connecting modern London directly to Boudica’s firestorm.

Who “won,” and what were the human costs on each side?

On raw numbers, Boudica’s revolt was one of the bloodiest episodes in Roman Britain. Ancient sources claim that around 70,000 to 80,000 Romans and provincials were killed in the sacked towns. Those figures are probably inflated, as Roman writers liked big, round numbers, but there is no doubt that civilian casualties were massive.

On the other side, Tacitus says around 400 Roman soldiers died in the early defeat at Camulodunum. In the final battle, he claims that about 80,000 Britons were killed versus 400 Romans. Those ratios are almost certainly propaganda. What matters is that Boudica’s army was shattered, and the revolt collapsed.

After the battle, Boudica disappears from the record. Tacitus says she took poison. Cassius Dio says she fell sick and died. Either way, she did not live to see the Roman reprisals. Suetonius launched harsh punishments on rebellious tribes. There was enough brutality that the imperial administration in Rome reportedly sent a new procurator to rein him in, worried that excessive cruelty might push Britain into permanent unrest.

Rome “won” in the narrow sense. The province stayed in the empire for three more centuries. Roads, forts, towns, and villas spread. Tribal autonomy shrank. Latin inscriptions multiplied. The Iceni as a political force vanish from history after a few decades.

They look similar if you only count the dead: both sides inflicted and suffered large-scale violence. The difference is what those deaths bought. For Rome, they bought continued control and revenue. For Boudica’s people, they bought a brief, terrifying moment of revenge and then silence.

So what? The outcome matters because it shows that even a spectacular, city-burning revolt could not dislodge Rome, but it also forced the empire to rethink how far it could push its subjects before they exploded.

How did Boudica and Rome each shape the long-term story of Britain?

In the short term, Rome learned from the disaster. After the revolt, there was a pause in aggressive expansion in Britain. Some policies softened. There was more attention to local elites and to not stripping provinces too quickly. The empire did not become kind, but it became more careful.

Londinium, Camulodunum, and Verulamium were rebuilt. London in particular grew into the main commercial and administrative center of Roman Britain. Its street grid, riverfront, and later stone walls all came after Boudica’s fire. The destruction horizon is literally the foundation for later growth.

Boudica, by contrast, vanished from Roman narratives after the first-century historians. For centuries, she was a footnote. Her legacy lived on not in continuous memory, but in the physical scars under towns and in scattered references.

In the early modern period, English and then British writers rediscovered her. She became Boadicea in Victorian spelling, a patriotic warrior queen. For an empire that ruled others, she was a convenient symbol of ancient resistance to foreign rule, safely in the past. Statues went up, including the bronze figure of Boadicea and her daughters in a chariot near Westminster Bridge, within sight of Parliament.

They look similar now as symbols. Rome as the bringer of roads and law. Boudica as the fiery rebel. The difference is that Boudica has been remade many times: Celtic freedom fighter, feminist icon, nationalist heroine. Rome’s image in Britain has also shifted, from civilizing force to colonizer. The same events feed very different modern stories.

So what? The legacy matters because it shows how one revolt and one burned city can be used to argue for empire, against empire, for female power, or for national identity, depending on who is telling the story.

Why does the Boudican Destruction Horizon still matter today?

When construction workers in London hit that red-black layer, they are not just finding old fire damage. They are touching the moment when a colonized people nearly tore a Roman province apart. The Boudican Destruction Horizon is a physical line between two Londons: a fragile frontier town and a rebuilt Roman city that would anchor centuries of urban life.

For archaeologists, it is a handy dating tool. If you find that layer, you know you are at around 60–61 CE. For historians, it is a rare case where text and soil line up cleanly. Tacitus writes of a city burned. The ground shows a city burned.

For everyone else, it is a reminder that the modern city sits on layers of violence and recovery. The office blocks and Underground lines run over a place where refugees once fled, where a governor weighed the lives of civilians against military survival, and where a queen chose fire over submission.

They look similar if you only see another archaeological horizon, one more band in a trench. The difference is that this one still shapes how London tells its own story, from school lessons about Romans and Celts to tourist plaques about Boudica.

So what? The destruction horizon matters because it anchors a dramatic story of resistance and empire in something you can see and measure, keeping Boudica’s revolt from drifting into pure legend.

Boudica and Rome look like simple opposites in a textbook: barbarian queen versus imperial legions. Put their origins, methods, outcomes, and legacies side by side, and the picture gets sharper. A client kingdom tried to work with an empire and was humiliated. A queen answered with fire. An empire answered with disciplined slaughter and then policy tweaks. Under modern London, the ash of that exchange still lies in place, a dark line under glass and steel.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was Boudica and why did she rebel against Rome?

Boudica was the queen of the Iceni tribe in eastern Britain in the first century CE. After her husband Prasutagus died, Roman officials tried to annex Iceni lands, flogged Boudica, and raped her daughters. These abuses, along with wider resentment of Roman rule and taxation, sparked her revolt around 60–61 CE.

What cities did Boudica destroy and what is the Boudican Destruction Horizon?

Boudica’s forces attacked and destroyed three Roman towns: Camulodunum (Colchester), Londinium (London), and Verulamium (St Albans). The Boudican Destruction Horizon is a thick red-black burn layer found under parts of modern London, created when Londinium was burned during the revolt. Archaeologists use this layer to date deposits to around 60–61 CE.

Did Boudica win any battles against the Romans?

Yes. Boudica’s forces overwhelmed the small Roman garrison at Camulodunum and destroyed the town, and they sacked Londinium and Verulamium when the main Roman army was away. However, when the governor Suetonius Paulinus finally confronted her with a concentrated force on ground of his choosing, the Roman legions defeated her much larger army in a single decisive battle.

How accurate are the ancient accounts of Boudica’s revolt?

Our main sources are the Roman historians Tacitus and Cassius Dio, who wrote decades after the revolt and had their own biases. They likely exaggerated numbers and emphasized rebel brutality to justify Roman actions. However, the general sequence of events and the destruction of the three towns are supported by archaeological evidence, especially the burn layers found at Colchester, London, and St Albans.