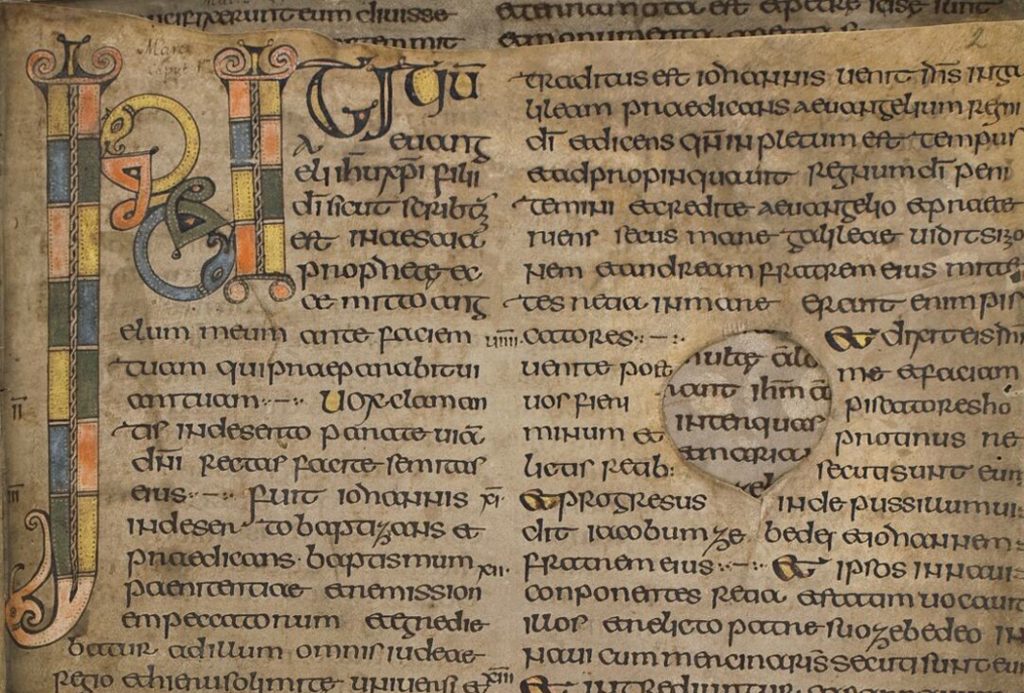

For 500 years, the words on one slip of parchment have been unreadable. The manuscript was used to bind a book of medieval poetry by a 16th-century bookbinder Now, thanks to state-of-the-art imaging technology, scientists have finally been able to read it at last.

The discovery was published in the journal Analytica Chimica Acta. The book itself is a 1537 copy of “Works and Days” by Hesiod, a famous Greek poet and contemporary of Homer. Northwestern University purchased the book two-hundred years ago, and it has remained with researchers ever since. While the contents of the book itself have been known for thousands of years, its binding – a manuscript in of itself – has remained a mystery.

Emeline Pouyet, a researcher with Northwestern University, explained that the binding caught their eye because they realized that the original bookbinder had attempted to remove text from the parchment – likely by washing or scraping the parchment. A closer look using x-ray imaging revealed two columns of writing.

“The ink beneath degraded the parchment, so you could start to see the writing,” Pouyet explained, “That is where the analytical study began.”

Emmaline Pouyet is the head researcher on this particular study.

Emmaline and her team sent the book to the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS) in Ithaca, New York – where another team of scientists used even more powerful x-rays to get a full picture of the text. The researchers then sent the images to their colleague, Richard Keickhefer, a professor of religion and history at Northwestern.

Keickhefer deciphered the text. Apparently, it’s a six-century Roman law code, with marginal commentary referencing Medieval Church canon law. The researchers believe that before the text was used as book-binding material, it was studied by Medieval students in a church’s university – a common practice during the Middle Ages.

Recycled Works

During the 15th-18th centuries, bookbinders often recycled Medieval and even older parchments for use as bindings for new, printed books. Parchment was stiff and durable, perfect for this use. It’s likely that the 16th-century bookbinder who recycled this manuscript decided it was outdated, and good only for bookbinding purposes. It was merely a Roman law document, after all.

This practice has long been known to modern researchers, but until now, they had no way of being able to reach the manuscripts recycled into bindings. With the new imaging system used by the Northwestern research team, hundreds of ancient manuscripts thought lost can now be read and deciphered.

“For generations, scholars have thought this information was inaccessible, so they thought, ‘Why bother?'” Marc Walton, the study’s senior researcher explained, “But now computational imaging and signal processing advances open up a whole new way to read these texts.”

Now that they know the technique works, Pouyet and Walton are looking for more hidden parchments to decipher.

“[Now], we can go into a museum collection and look at many more of these recycled manuscripts and reveal the writing hidden inside of them,” Walton said.

There’s no telling what they may find.