Last time, on Battles That Made History, we covered Salamis Bay: the historical naval battle that was responsible for crushing the Persian invasion of Greece and ensuring the survival of Western civilization as we know it today.

Today, we’re covering the famous battle of Waterloo. After 23 years of turmoil and war and one exile and one escape, Napoleon’s power over France and Europe would finally be destroyed by the combined military might of several European powers led by the Duke of Wellington and Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher.

It was fought just three miles outside of Waterloo proper. The battle would put the tiny village on the map and change the world forever.

Napoleon’s Return

![A photograph of modern-day Elba. [PHOTO: newmedia.thomson.co.uk]](https://historythings.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/EUROPEMEDITERRANEANITALYCON_ITAELBAELBARES_L34781.jpg)

Napoleon set foot on French soil on March 1st, 1815, landing with 1,000 men. Almost immediately, he won the support of the French people and marched on Paris. Fearing for his life, the reinstated monarch, Louis XVIII, fled, and Napoleon once again resumed his seat of power for what would be called ‘Napoleon’s Hundred Days’.

The Brewing Storm

News of Napoleon’s return to power spread like wildfire throughout Europe. The main Europen powers quickly rose to action and mustered their own forces, assembling their armies to meet Napoleon in open field. They had no intention of letting him regain his former glory and terrorize Europe again.

![The Duke of Wellington [PHOTO: historytoday.com]](https://historythings.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Duke-of-Wellington.jpg)

Wellington was joined by a Prussian force 45,000 strong, led by Prussian general Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher. It was an alliance that would prove to be invaluable in Napoleon’s eventual defeat.

![[PHOTO: napoleonbonaparte.wordpress.com]](https://historythings.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/blucher.jpg)

At Ligny, Napoleon led the assault on the Prussian force led by Blücher. Over the course of the battle, hordes of Prussians either defected to the French or deserted, but even so, due to miscommunication between the French commands, the Prussians survived long enough to retreat.

The French miscommunication at Ligny was a harbinger of what was to come for Napoleon at Waterloo.

Once the Prussians were on the run, Napoleon wheeled his huge army around and turned on Wellington, leaving a third of his forces to keep an eye on the Prussians and protect his flanks. Even with the widening gap between Wellington and Blücher, the two maintained strong lines of communication and coordinated their movements accordingly.

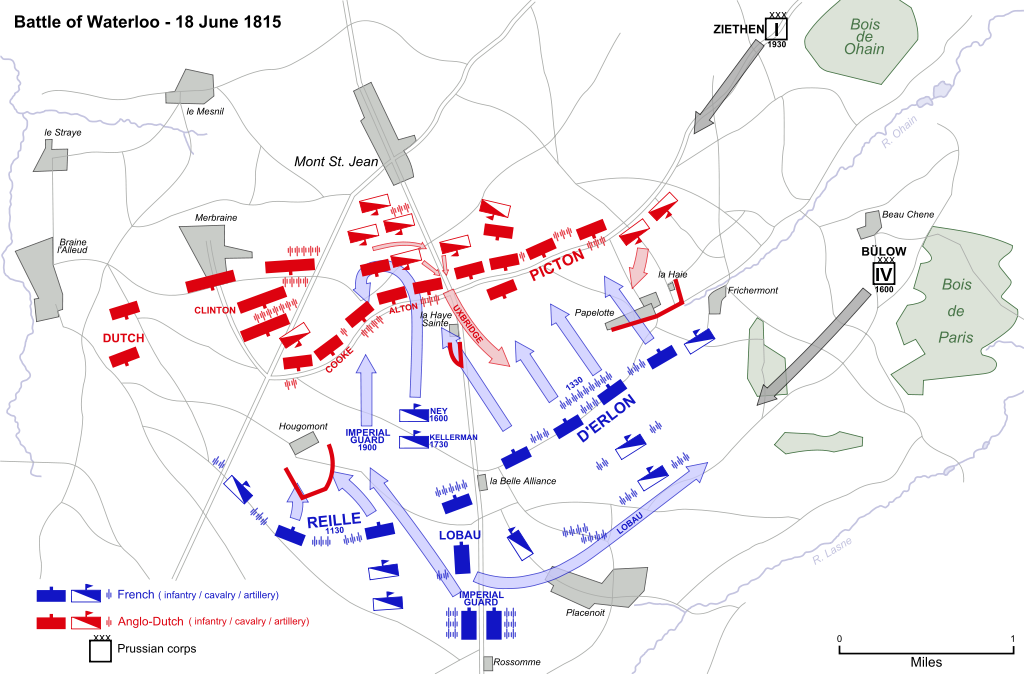

Instead of standing and fighting, Wellington decided to retreat to Waterloo – a highly defensible position bounded by ridges. He took up a strong defensive position along a ridge south of Mont-Saint-Jean, and it was there that he began to set up his troops for the impending battle.

The Battle

As he waited for Napoleon to arrive with his army in tow, Wellington began moving his troops into strategic positions. He took an unpaved road with heavy hedges that shielded his troops from artillery, and held outposts at a local chateau at Hougoumont and several other outlying farms.

He had made expert use of his terrain; he had to. His 67,000 men and 156 guns were no match for Napoleon’s 72,000 men and almost twice as many artillery. His Prussian allies were far behind, and Napoleon’s massive army was right in between them. Things were not looking good for Wellington.

![A view of the battlefield. Top right are the road and the buildings of La Haye Sainte. [PHOTO: wikimedia]](https://historythings.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Belgium-6773_-_Battlefield_View_14152126362.jpg)

The first shots were fired by Charles Reille’s artillery, the French side. Taking Hougoumont should have been easy, but the attack was badly managed and all it did was eat through Napoleon’s forces.

It was 1:00 PM. While the fighting at Hougoumont raged on, Napoleon was gearing up to order an artillery attack on Wellington’s center, but was distracted by a mass of troops emerging from the woods of Chapelle Saint-Lambert, 6 miles northeast. A messenger arrived and told him the dreaded news: the mass of troops was Prussian. They’d caught up, and they posed a huge threat to Napoleon’s flanks. Immediately, Napoleon sent a dispatch to his generals, telling them to rejoin the main army and support him, but the message wouldn’t reach his second-in-command until 5 PM. By then it would be far too late.

With no help on the way, Napoleon did the only thing he could. He assigned two cavalry units to the northeast to screen the Prussian’s path and keep them at bay. The command was carried out by 1:30.

With his flanks reasonably secure, Napoleon then marched on Wellington with 18,000 unaccompanied infantry. It was a blunder. Wellington met the attack with full firepower.

![Charge of the 2nd Guard Lancers [PHOTO: wikimedia]](https://historythings.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Charge_des_lanciers_de_la_Garde_à_Waterloo_détail_du_Panorama_de_Waterloo.jpg)

Wellington called his cavalry back to the center, but two of his commanders – Lord Edward Somerset and Sir William Posonby, flushed with success, ignored him. They charged the French, and both commanders were killed. The attack was a stupid waste that Wellington couldn’t afford. It destroyed a good part of his cavalry base and lost him 3,000 French prisoners.

By 3:00 PM, both sides were getting tired. Hougoumont was still tangled up between the French and English forces. Napoleon ordered his commander, Ney, to take La Haye Sainte, but the English held their ground. Anxious to win the position, Ney sent the bulk of French cavalry to follow up his troops without consulting anyone. The British formed infantry squares – an open-field tactic that had been proved to be immensely successful against cavalry charges. As a result, Ney singlehandedly lost the bulk of the French cavalry in one charge.

An hour and a half later, the tide was turning against Napoleon. – Blücher’s Prussians arrived in full force and swarmed over the northeastern hills, overwhelming Napoleon’s cavalry screen.

By five o’clock, Ney was desperately trying to regain his honor as a general and pierce the English front. He expended the last remnants of his cavalry on the attempt, and then sent in 6,000 idle infantry. Wellington met him with heavy artillery and small arms and the French had to fall back, losing a quarter of the men.

The clock was ticking on Napoleon. It was a race to overwhelm Wellington’s forces and regroup before Blücher could reach them. By 6:00 PM, Napoleon ordered a full assault on all the farms. It came down to a dire, bloody, hand-to-hand battle. Napoleon knew Wellington’s reserves were almost exhausted with heavy casualties and desertions. The center was wide open if only the French could regain some morale and energy and intensify their attack. In a surge of success, The French recaptured the left, and kept hitting Hougoumont with full force. The duke had no reinforcements. His forces were tired, depleted, and hard-hit. As soon as Ney noticed Wellington’s forces starting to break, he called for reinforcements.

But, with the Prussians descending on Napoleon’s right flank, Napoleon refused. He couldn’t spare any more men to Ney without risking losing his entire right side to Blücher’s armies.

By 7:00 PM, Napoleon managed to secure his flank and turn to the front. He ordered six battalions to reinforce Ney, but Wellington had had half an hour to reorganize in the absence of French backup. In that time, Wellington had quickly shored up his center and cleared the French from the ridge before reinforcements hit, and took out the artillery at La Haye Sainte.

By the time Ney had failed with the follow-up attack, the Prussians dove in and overwhelmed the outlying outposts. The French Guard was defeated, and Wellington ordered a general advance. Realizing all was lost, Napoleon’s army was thrown into confusion.

A two-hour bloodbath ensued. At 9:00, Wellington and Blücher met in the center of the Waterloo battlefield. By then, the French had taken flight. The combined English and Prussian armies chased them for 11 miles south.

In just one day, Napoleon was finally defeated, but not without cost. Wellington had lost 20,000 men, and Napoleon had lost 25,000. During the flight, 9,000 French men were captured by the pursuing forces.

End of an Era

The defeat at Waterloo was Napoleon’s last, ending 23 years of warfare between France and the rest of Europe.

Napoleon returned to Paris on June 21 and abdicated on the following day. The French army was disbanded. Louis XVIII was restored to rule in France. After that, Napoleon planned to escape to the United States, but was thwarted on the way by English soldiers. Once captured, Napoleon surrendered, and then was sent to a much harsher exile on the barren island of St. Helena for the rest of his life.

It would be the end of the Napoleonic Era. Post-Napoleonic Europe would have to cope with the loss of hundreds of thousands of men from the previous wars. There would be a time of peace and quiet, a restoring of the balances of power until Europe once again erupted into conflict during the revolutions of 1848.

Until then, thanks to the Duke of Wellington and General von Blücher, all would be well.