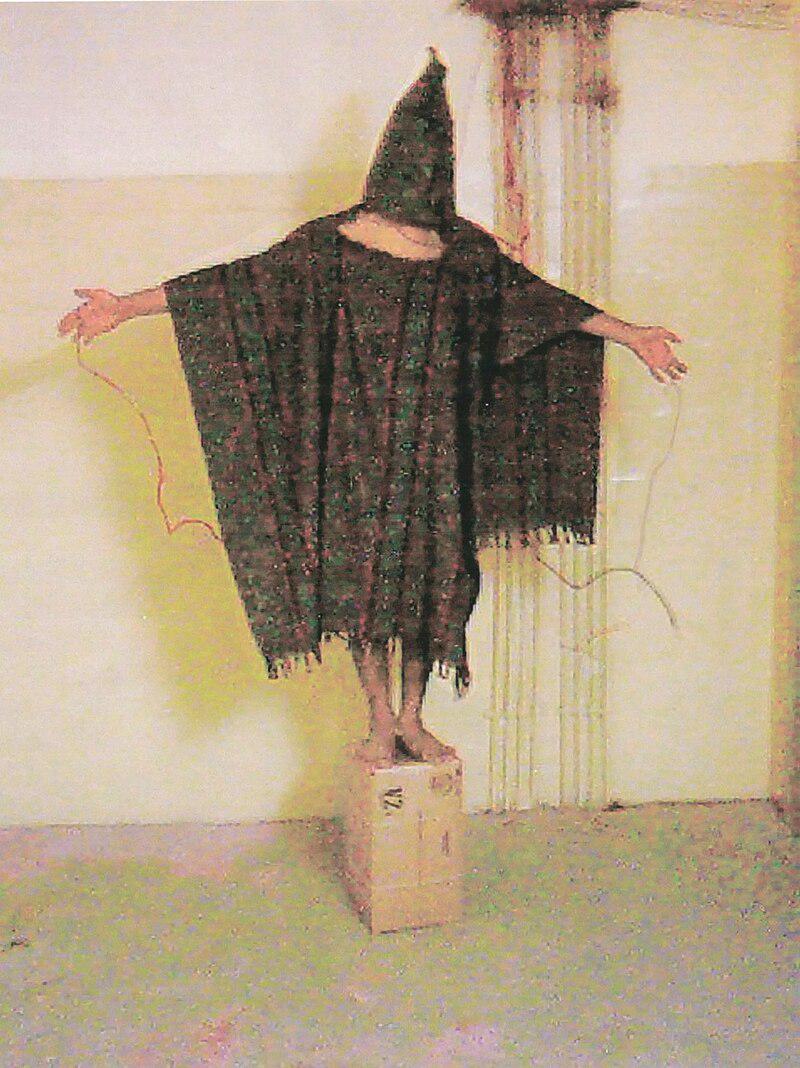

He is barefoot on a cardboard box, arms out like a broken scarecrow. A poncho covers his body, a hood covers his head. Wires run from his fingers. The caption that raced around the world in 2004 said: if he falls off the box, he will be electrocuted.

The photo of the “Hooded Man” at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq became one of the defining images of the Iraq War. To many viewers, it looked disturbingly familiar. Hooded detainees, stress positions, dogs, orange jumpsuits. It looked like Guantánamo Bay.

They look similar because Abu Ghraib and Guantánamo grew from the same post‑9/11 logic about a new kind of war and a new kind of prisoner. Both were products of legal improvisation, intelligence pressure, and a White House convinced that old rules were a luxury.

By the end of this story you will see how two very different places, one in Cuba and one outside Baghdad, ended up sharing methods, language, and a long shadow over American power.

Why did Abu Ghraib and Guantánamo start in the first place?

Guantánamo Bay came first. In January 2002, the first detainees in orange jumpsuits arrived at the U.S. naval base in Cuba. They were captured in Afghanistan and Pakistan after the U.S. invasion that followed the 11 September 2001 attacks.

The Bush administration called them “unlawful enemy combatants”. That phrase mattered. It was meant to put them outside the protections of the Geneva Conventions that apply to prisoners of war. Lawyers in the White House and the Justice Department argued that the war on terror was a new kind of conflict, so old rules did not fully apply.

Guantánamo was chosen because it was under U.S. control but not on U.S. sovereign territory. Officials believed that made it a legal grey zone, where detainees would have limited access to U.S. courts. The camp was built to hold people indefinitely, question them for intelligence, and keep them away from public view.

Abu Ghraib had a different origin story. It was a notorious prison under Saddam Hussein, used for mass executions and torture. After the U.S. invaded Iraq in March 2003 and toppled Saddam, the U.S. military took over the site. By mid‑2003, it was the main U.S. detention facility for Iraqis suspected of attacks or of having information about the insurgency.

On paper, Abu Ghraib was part of a more traditional war. The U.S. was an occupying power in Iraq, so the Geneva Conventions clearly applied. Detainees there were supposed to be treated as prisoners of war or civilian internees with legal protections.

The link came from Washington. In 2002 and 2003, senior officials approved new interrogation policies for Guantánamo that stretched or redefined bans on torture. Some of those techniques, and the underlying logic, migrated to Iraq.

So what? The two prisons started for different reasons, but both were shaped by the same post‑9/11 decision to carve out exceptions to established rules, which set the stage for similar abuses.

How did legal theories shape what happened inside?

To understand why the Hooded Man ended up on that box, you have to start with memos, not photographs.

In August 2002, the Office of Legal Counsel at the U.S. Justice Department issued a memo, later called the “torture memo.” It argued that for pain to count as torture under U.S. law, it had to be equivalent to organ failure or death. It also claimed that the president’s commander‑in‑chief powers could override anti‑torture laws in wartime.

These memos were written with Guantánamo and CIA black sites in mind. They cleared the way for harsher interrogations of high‑value detainees. Techniques like stress positions, forced nudity, sleep deprivation, and exposure to cold were discussed and, in some cases, approved.

In December 2002, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld signed a memo approving a list of aggressive techniques for Guantánamo interrogations, including stress positions for up to four hours, removal of clothing, and using dogs to induce fear. He famously scribbled in the margin about standing for four hours: “I stand for 8–10 hours a day. Why is standing limited to 4 hours?”

By 2003, the war in Iraq was going badly. Insurgents were attacking U.S. troops. Intelligence officers complained they were not getting enough information from detainees. Senior commanders in Iraq asked for more “effective” interrogation methods.

Policies and attitudes that had been tested at Guantánamo were exported. A team of interrogators from Guantánamo, led by Major General Geoffrey Miller, visited Iraq in August–September 2003. His mission was to “Gitmo-ize” Iraqi detention, to make it more useful for intelligence.

After Miller’s visit, new interrogation rules in Iraq authorized stress positions, environmental manipulation, and the use of dogs. Even where the written rules were more limited than Guantánamo, the message that harsher treatment was desired had been sent down the chain.

So what? Legal contortions designed for Guantánamo did not stay contained. They lowered the bar on what was considered acceptable, and that permissive climate spread to places like Abu Ghraib.

What methods did guards and interrogators actually use?

From the outside, Abu Ghraib and Guantánamo looked similar: razor wire, guard towers, hooded men in jumpsuits. Inside, some of the methods overlapped, even if the scale and visibility differed.

At Guantánamo, early photos showed detainees in orange jumpsuits, kneeling, shackled, wearing goggles and earmuffs. The official line was that they were dangerous terrorists. Interrogation methods varied over time and by detainee, but documented techniques included prolonged isolation, stress positions, sleep deprivation, exposure to cold, loud noise, and sexual humiliation.

One Guantánamo detainee, Mohammed al‑Qahtani, suspected of involvement in the 9/11 plot, was subjected to a 50‑day interrogation plan in late 2002 and early 2003. Declassified logs show he was deprived of sleep, forced to stand, stripped, led on a leash, and made to bark like a dog. The Pentagon later admitted his treatment was abusive and dropped war crimes charges against him.

At Abu Ghraib, the abuses were more chaotic and often mixed sadism with interrogation. Between October and December 2003, U.S. Army reservists in the 372nd Military Police Company took photos of detainees forced into naked human pyramids, threatened with dogs, smeared with fake menstrual blood, and made to simulate sexual acts.

The Hooded Man photo came from this period. The prisoner, identified in some accounts as an Iraqi named Abdou Hussain Saad Faleh, was told that if he fell off the box he would be electrocuted. The wires were attached to his fingers, but there is no evidence they were actually connected to a power source. The point was terror, not information.

Both sites used sensory deprivation and disorientation: hoods or goggles, loud music, bright lights. Both used stress positions that caused intense pain without leaving obvious marks. Both blurred the line between punishment and interrogation.

There were differences. Guantánamo was more controlled, with detailed interrogation plans for specific detainees and more direct involvement from senior officials. Abu Ghraib mixed official policy with breakdowns in discipline, overcrowding, and poorly trained reservists left in charge.

So what? The shared toolkit of hooding, stress positions, and humiliation shows that Abu Ghraib was not just a few rogue guards. It reflected a broader shift in U.S. practice that Guantánamo helped normalize.

What were the outcomes for detainees and for the U.S.?

For detainees, both prisons meant years lost in a legal black hole.

At Guantánamo, about 780 men have been held since 2002. Many were never charged with a crime. Some were eventually cleared for release but remained for years because no country would take them. A small number were charged in military commissions, a special court system created for the war on terror.

Hunger strikes and force‑feeding became regular features at Guantánamo. Former detainees reported long‑term physical and psychological damage: PTSD, chronic pain, nightmares. Some were later found to have been low‑level fighters or even picked up on bad intelligence or local vendettas.

At Abu Ghraib, the numbers were smaller but still significant. By late 2003, the prison held around 7,000 detainees. Many were Iraqis swept up in broad raids, sometimes with little evidence. After the scandal broke, U.S. investigations found that at least several dozen detainees had been abused, and at least one, Manadel al‑Jamadi, died during interrogation at the prison.

For the United States, the costs were political and strategic.

When CBS’s “60 Minutes II” aired the Abu Ghraib photos in April 2004, the images exploded across Arab media. The Hooded Man, the naked pyramid, the snarling dogs. They fed a narrative that the U.S. occupation of Iraq was not about liberation but humiliation.

Insurgent groups used the photos in propaganda and recruitment. The scandal damaged U.S. credibility when it criticized other governments’ human rights records. President George W. Bush called the abuses “abhorrent” and said they did not represent America, but the images were hard to argue with.

Guantánamo became a symbol in its own right. For many outside the U.S., the word “Gitmo” came to mean indefinite detention without trial. Allies complained. Human rights groups campaigned for closure. The U.S. Supreme Court, in a series of cases starting with Rasul v. Bush in 2004, ruled that Guantánamo detainees had the right to challenge their detention in U.S. courts.

So what? Abu Ghraib and Guantánamo did not just harm the people inside the wire. They damaged U.S. legitimacy, fueled enemies’ narratives, and forced legal and political reckonings that are still ongoing.

How did accountability and public exposure differ?

One big difference between Abu Ghraib and Guantánamo is how the world found out what was happening.

Abu Ghraib exploded into public view because low‑level soldiers took photographs, and those photos leaked. Specialist Joseph Darby, a member of the 372nd Military Police Company, gave a CD of images to Army investigators in January 2004. When CBS and The New Yorker published them a few months later, the scandal was impossible to contain.

The Army launched multiple investigations. The most famous, the Taguba Report, documented “sadistic, blatant, and wanton criminal abuses.” Several enlisted soldiers were court‑martialed. Private Lynndie England, seen in photos holding a leash attached to a naked detainee, received a three‑year sentence. Staff Sergeant Ivan Frederick got eight years.

Senior officers were reprimanded or relieved of command, but no general or cabinet‑level official faced criminal charges for Abu Ghraib. The narrative from the Pentagon focused on “a few bad apples” rather than systemic policy.

Guantánamo’s story came out more slowly, through leaked memos, declassified documents, and detainee accounts. There were no shocking photo sets equivalent to Abu Ghraib. Journalists and lawyers gradually pieced together interrogation logs, Red Cross reports, and internal emails.

Legal accountability at Guantánamo played out in courtrooms rather than courts‑martial. The Supreme Court ruled several times that the administration had overreached: detainees had habeas corpus rights, and the original military commissions violated U.S. law and the Geneva Conventions.

Yet, as with Abu Ghraib, senior architects of the policies avoided criminal prosecution. The Justice Department’s own ethics office criticized the torture memos, but the lawyers who wrote them kept their careers.

So what? Abu Ghraib produced vivid, unforgettable images and punishment for low‑ranking soldiers, while Guantánamo produced legal battles and policy debates. Together they show how visual evidence and secrecy shape who gets blamed and what the public remembers.

What is the legacy of the Hooded Man and Guantánamo today?

The Hooded Man photo became a shorthand for American abuse in Iraq. It appeared in protests from Cairo to London. Artists reworked the silhouette in paintings, posters, and installations. For many Iraqis, it fused with older memories of torture under Saddam, creating a bitter sense that one occupier had replaced another.

Guantánamo’s image is less about a single photo and more about an orange jumpsuit. That color, once just a prison uniform, became a symbol used by both sides. Detainees wore it in early Guantánamo photos. Years later, ISIS forced hostages to wear orange jumpsuits in execution videos, a deliberate echo.

Both places changed how the world talks about the United States. When U.S. officials now criticize torture or arbitrary detention abroad, they often hear one word in response: “Guantánamo” or “Abu Ghraib.” The moral high ground is harder to claim.

Inside the U.S., the legacy is mixed. President Barack Obama ordered Guantánamo closed in 2009 but ran into congressional resistance. The prison is still open, with a few dozen detainees. Some have been cleared for transfer but remain stuck. Military commissions for 9/11 suspects have dragged on for years without a final verdict.

The legal theories that allowed harsh interrogations have been formally abandoned, and the most notorious memos withdrawn. Official policy now rejects torture. Yet the memory of how quickly rules were bent after 9/11 lingers in debates about national security and civil liberties.

Abu Ghraib prison itself was handed back to the Iraqi government and later closed. Parts of it were reportedly used by Iraqi authorities, then by ISIS when it swept through the area. The site’s association with abuse did not end with the Americans.

So what? The Hooded Man and Guantánamo are not just dark chapters in a history book. They reshaped global views of U.S. power, influenced how enemies and allies respond, and left legal and moral questions that still shape policy today.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why did the Abu Ghraib torture look similar to Guantánamo?

They looked similar because both grew from the same post‑9/11 policies. Legal memos and interrogation rules first developed for Guantánamo, including stress positions, hooding, and use of dogs, were later exported to Iraq. That shared policy framework produced similar abuses in very different places.

Was the Hooded Man at Abu Ghraib really being electrocuted?

The wires attached to the Hooded Man’s fingers were meant to convince him he would be electrocuted if he fell off the box. Investigations found no evidence the wires were connected to a power source. The threat and psychological terror were real, even if actual electrocution did not occur in that moment.

How many people were held at Guantánamo and Abu Ghraib?

Since 2002, about 780 men have been held at Guantánamo Bay, most without formal charges. At Abu Ghraib under U.S. control, around 7,000 detainees were held at the height of operations in late 2003. Many at both sites were eventually released without being tried for a crime.

Did any high‑ranking U.S. officials face charges for Abu Ghraib or Guantánamo?

No senior military or civilian leaders were criminally charged for policies at Abu Ghraib or Guantánamo. At Abu Ghraib, several low‑ranking soldiers were court‑martialed and sentenced to prison. At Guantánamo, accountability came mainly through court rulings that limited government power, not through prosecutions of top officials.