Yahya Jammeh, the former leader of The Gambia, only last week ceded to the December election winner, Adam Barrow. He’s only the most recent case. There are too many to count throughout history, but modern history is more riddled with reluctant leaders than one might assume.

It wasn’t long ago the Arab spring ousted leaders from their respective thrones in Egypt and Libya. Closer to home, Dilma Rousseff in Brazil was once not so keen on stepping down, but eventually accepted her impeachment.

Nicolás Maduro remains the president in an impoverished Venezuela as does Paul Biya in Cameroon. The international community insists Biya is only in power due to rigged elections. The list goes on and on…

It takes little stretch of the imagination to understand why power is a hard handle to release. Many of these leaders rose from nothing. It’s as much about the lifestyle they would relinquish as anything.

The problem only worsens once a sitting leader hesitates. The moment they choose to stay, there is no going back. The alternative is jail or even death, as we saw with Muammar Gaddafi.

Whatever the outcome of an election in the developed world, we don’t fret the possibility of despots. So far, we’ve enjoyed a tradition of peaceful power transfer. In contrast, the history of the world is more notably that of leaders with no intention of going quietly.

Yes, we all know Hitler was a bad guy, Joseph Stalin rebranded communism and Julius Caesar was the jerk who upset 500 years of peaceful secession. Let’s not talk about them anymore.

Here instead are five lesser-known historic leaders, worthy of our vitriol, who refused step down.

Sukarno | Indonesia |1945-1966

As so many of these stories begin, Sukarno was instrumental in releasing his country from occupation by the Netherlands. He even spent over 10-years in a Dutch prison until Japanese forces released him.

While at first Sukarno united the people of Indonesia, in the ‘60s his presidency progressed towards a communist party, the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI).

As part of his plan for “guided democracy,” he disbanded the elected parliament with one president-appointed. No surprise that Russia and China were there to support him, but they could not save Sukarno from the will of the people.

On October 1st in 1965, a coup e’état comprised of Indonesian National Armed Forces, assassinated six generals and replaced Sukarno with Suharto, a General from the same armed forces.

Fortunately for Sukarno, the people did not wish his death. They held him under house arrest until he died of kidney failure in 1970.

Idi Amin Dada | Uganda | 1971 to 1979

Idi Amin Dada owns somewhere between 100-500,000 unlawful deaths under his rule.

He came to power in a military coup, where they removed Milton Obote, the leader who had previously led Uganda to independence from the British. They made Amin Dada the head of state.

Obote fled to Tanzania where 20,000 refugees from Uganda joined him. This created tension between Amin’s Uganda and Tanzania, tension that would come back to haunt him.

During his bloody rule, Amin Dada enjoyed support from the esteemed Muammar Gaddafi, but also the Soviets and Eastern Germany. In 1977, after Britain ended relations with Uganda, Amin Dada declared himself president of Uganda.

Meanwhile, tension with Tanzania escalated into war. After eight years of oppression and in light of the escalating war with Tanzania, Amin fled to Saudi Arabia in 1979. He left behind a bedraggled country, one that would struggle for years to find stability.

In 2003, in a strange echo of Sukarno’s of Indonesia’s death, Amin Dada died of kidney failure.

Didier Ratsiraka | Madagascar | 1975 to 1993/1997 to 2002

When Ratsiraka first took power in 1975, it was as a socialist leader. According to the then government of Madagascar, he received 95% of the vote. When the country re-elected him in ’82, it was with 80% of the vote, then 63% in the ’89 election.

The opposing party in 1989 condemned Ratsiraka’s election as a fraud. By 1991 the opposition to Ratsiraka culminated in violent protests at the Presidential Palace. In that incident, Guards of the Palace opened fire on the citizens.

It was only months later that Ratsiraka agreed to relinquish power to the High Authority of the State, Albert Zafy. Ratsiraka remained president, even though he had no power.

He lost the election in ’93, beaten by Zafy, but then Madagascar impeached Zafy in 1996 but didn’t ask him to leave or deny him the right to run for president again in the future.

In the 1997 election, Ratsiraka won the election again. Zafy and others attempted to impeach Ratsiraka after that election, but they did not succeed.

In 1991, he finally lost to Marc Ravalomanana. The short version of what happened next is Ratsiraka fled to France, but not before stealing $8-million in public funds.

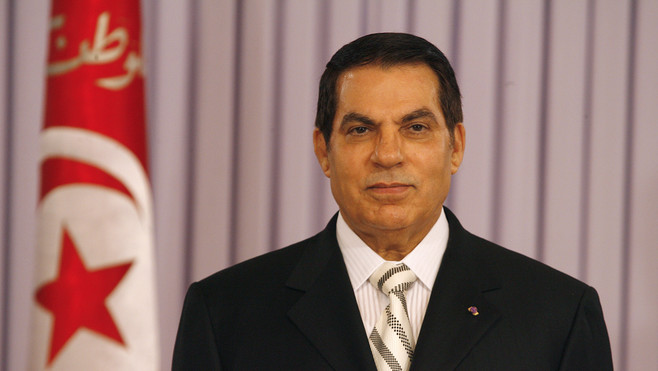

Zine El Abidine Ben Ali | Tunisia | 1987–2011

Ben Ali came to power in Tunisia after a bloodless coup in 1987. He promised to create a democratic government, loosened the restrictions on the press, and changed the controlling party’s name from socialist to democratic, but the people weren’t so convinced.

They saw the actions of his government as deceptive. Every election after the first he won by greater than 90% of the vote until his final re-election in 2009. Despite all those votes, the people rose up in 2011 to protest his rule.

In response to the protests, Ben Ali dissolved the government, declaring a state of emergency. He promised reform, but his progress toward that goal dissatisfied the people.

Realizing his decreasing and limited options, Ben Ali fled with his family to Saudi Arabia.

The Tunisian government then asked Interpol to assist in arresting him for money laundering and drug trafficking. Authorities tried Ben Ali and his wife in absentia, finding them guilty. Then, in 2012, a Tunisian court found him guilty of inciting violence, sentencing him to life in prison, again in absentia.

Despite a stroke in 2011, Ben Ali remains alive in exile in Saudi Arabia.

Laurent Gbagbo | The Ivory Coast | 2000 to 2011

Gbagbo started as a history professor, a man who’d studied at Paris Diderot University. In 1971 he’d spent time in jail as an opponent of the then president Felix Houphouët-Boigny, but by 1980 he took a job as the Director or the Institute of History Art.

After a 1982 teacher’s strike, he went into exile, determined to return and restore infrastructure to the Ivory Coast. He formed the Ivorian Popular Front (FPI) then returned in 1988, taking the position of Secretary General for the party.

By ’96 he was the president of that party. The FPI chose Gbagbo as their candidate for the 2000 election, which was (in short) a mess ending with Gbagbo in the seat of power.

Gbagbo’s rule expired in 2005, but he delayed elections until 2010. He lost that election to Alassane Ouattara, but similar to the recent events in the Gambia, Gbagbo’s party claimed a fraud.

After a questionable review of the votes, a council determined that Gbagbo should have won. He ordered the army to close the borders, but Gbagbo could only hide for so long.

In 2011, forces from the UN and France, along with the rising coup, fired on Gbagbo’s residence to smoke him out. They arrested him, then tried him in an International Criminal Court, the first time the ICC has tried a former leader.

Gbagbo remains locked up in the Hague, charged with murder, rape at the top of the list.

It seems a low bar, but considering these account for only a handful of such accounts, one has to be grateful to live in a country where we pass the torch without bloodshed.